Difficult Run: Exploring Potomac Tributaries

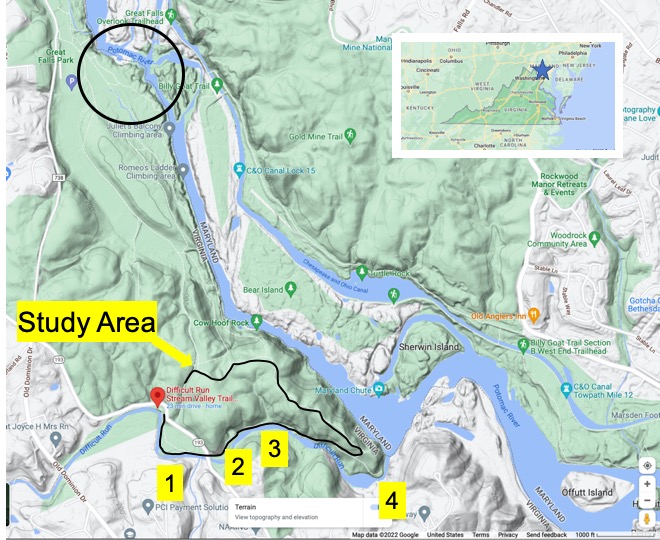

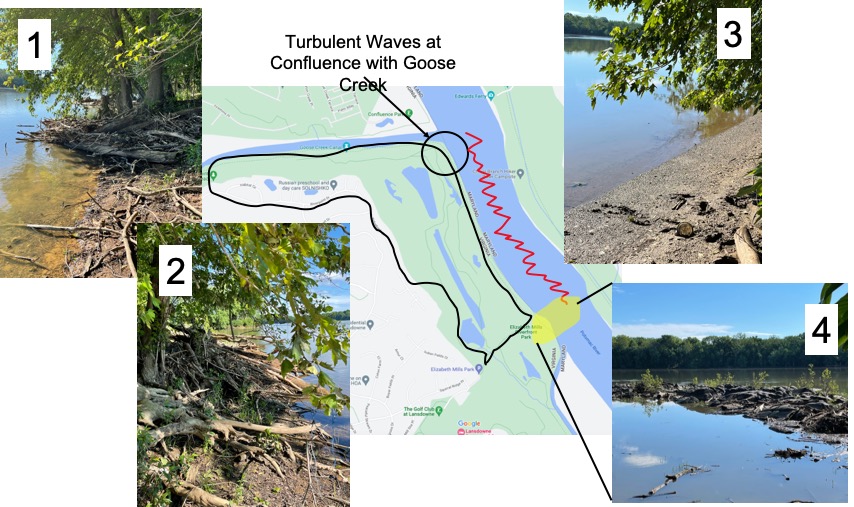

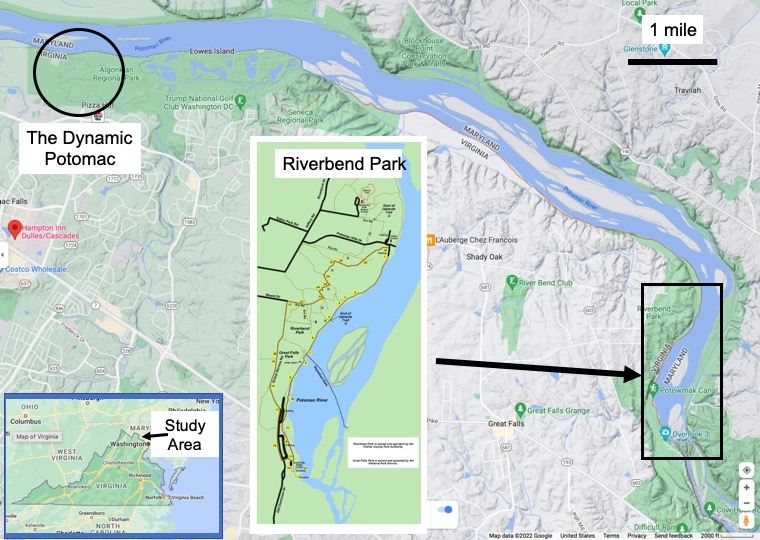

This week we went exploring south of Great Falls, along a tributary that cuts through Precambrian metamorphic rocks, before joining the Potomac River.

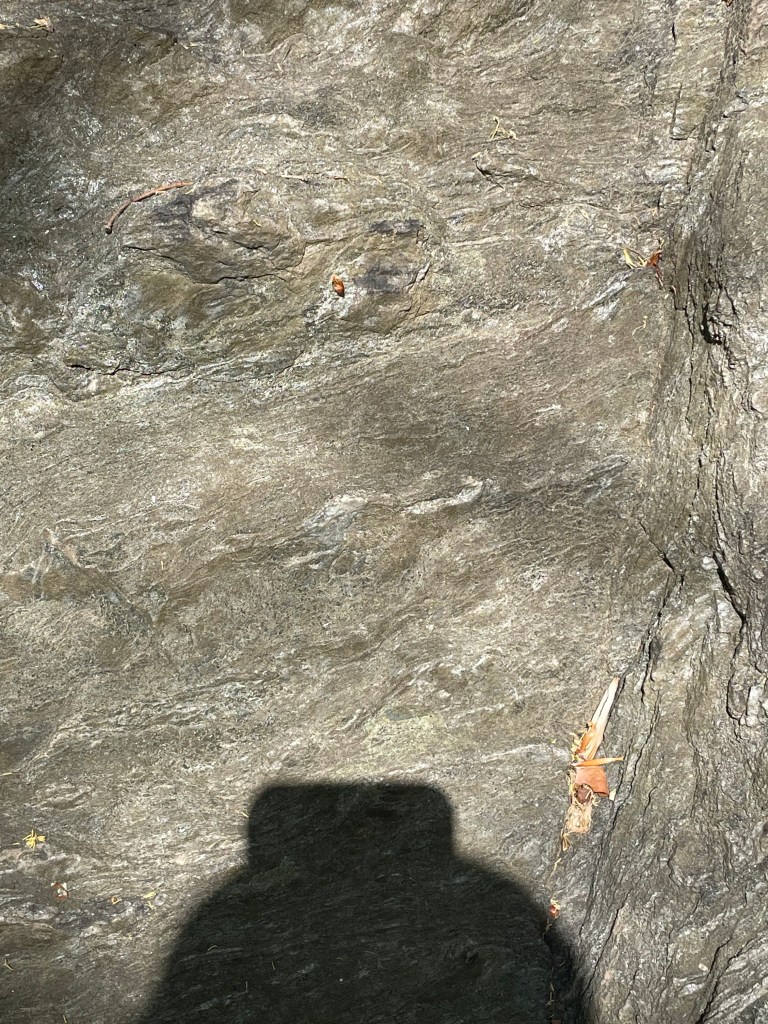

Difficult Run twists its way through a mass of hard rocks that we have met before, Precambrian Schist and gneiss, forming a series of quiet pools (Fig. 3) separated by resistant, rocky sections (Fig. 4).

It was a shady walk beneath a tall canopy of mature hickory, ash, and other temperate forest trees. There was plenty of evidence of the recent spring floods. Large trees were jammed up on rocky outcrops and among the trees covering the floodplain. After a short hike, we came to what looked like an abandoned quarry (Fig. 4), which can be identified by the bright spot in the relief map of Fig. 2, just above the label for Site “2”.

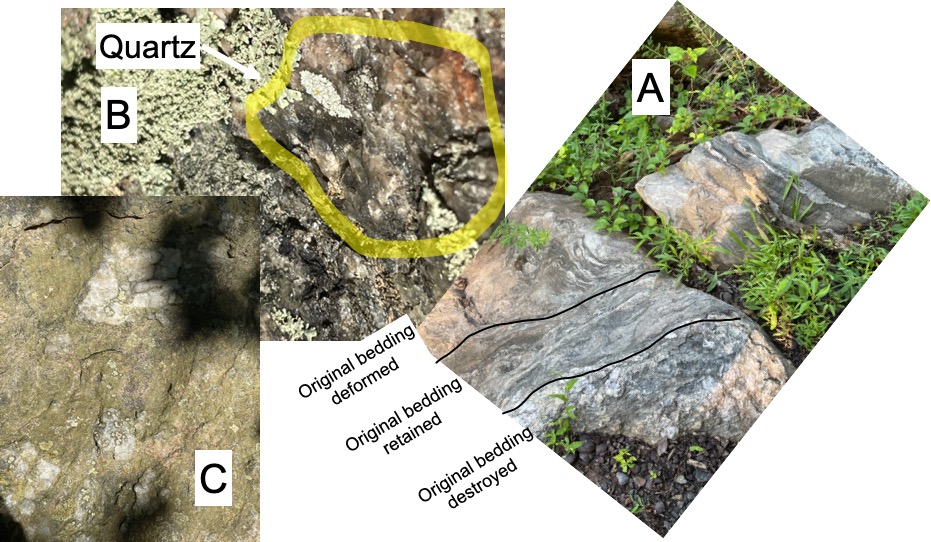

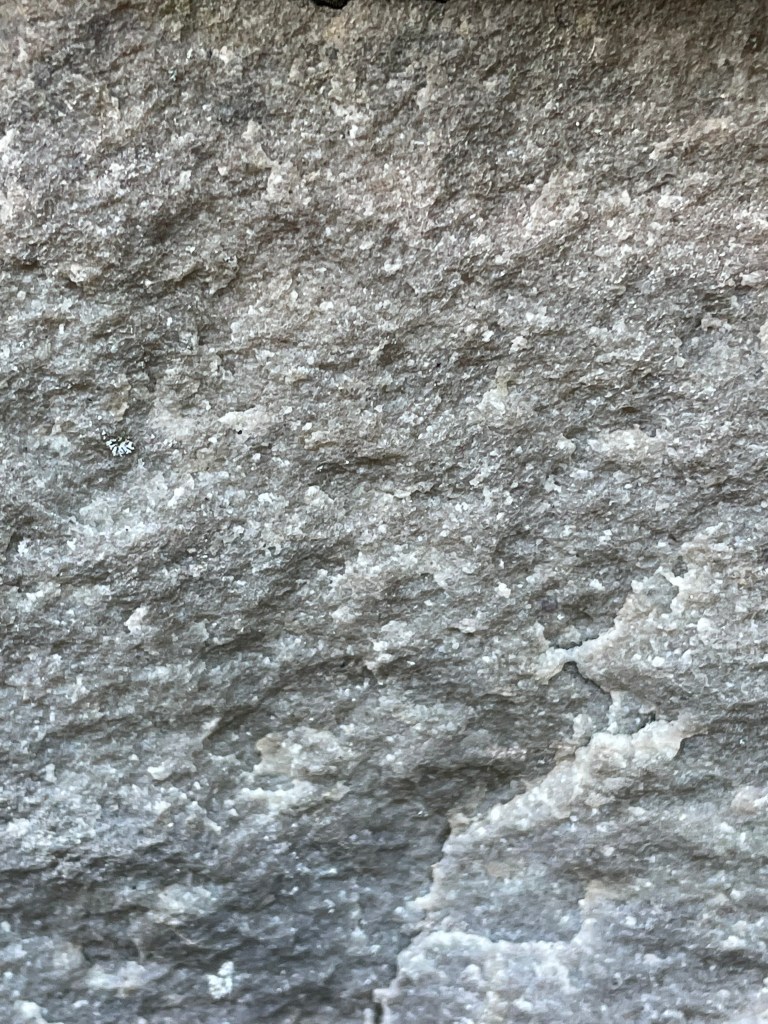

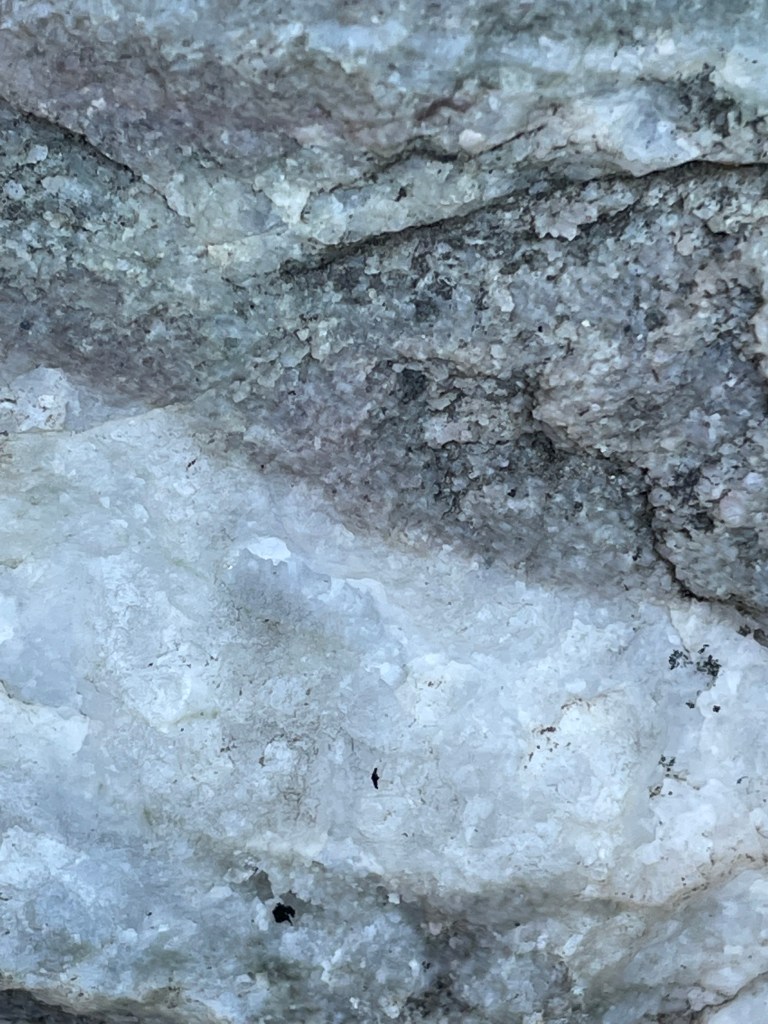

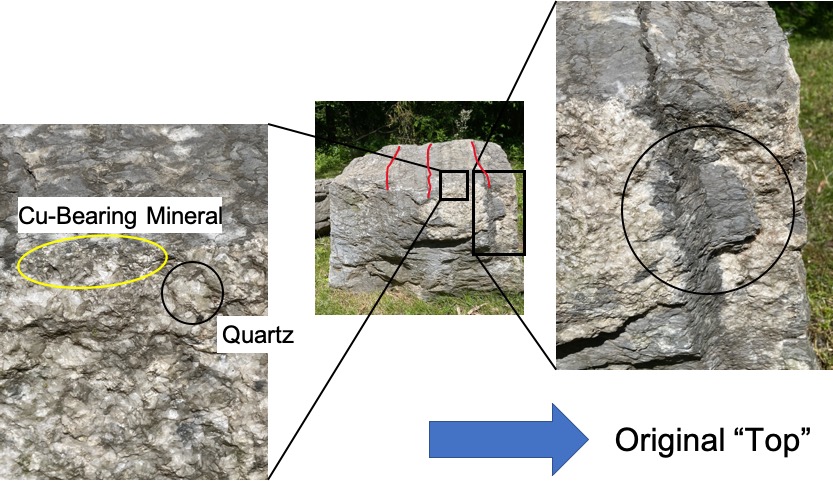

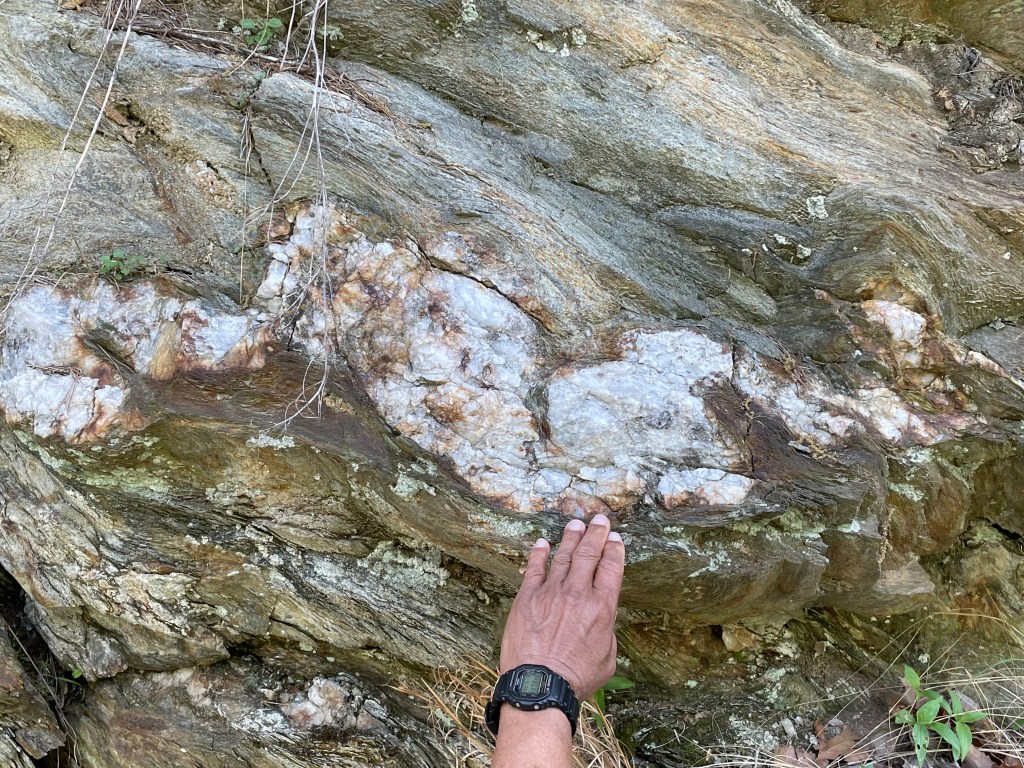

I was able to examine several slabs of the rock exposed in the quarry and along the river bed (see Fig. 1 for appearance) at Site 2, revealing foliation and inclusions similar to other exposures of this rock (Fig. 5).

We’ve seen the structures displayed in Fig. 5 before, in this same rock, at Great Falls and other locations along the Potomac River. I’m presenting these examples to give the reader some idea of the scale of these processes. For example, the juxtaposition of foliation in Fig. 5A suggests a frenzy of activity, like in a pan of boiling water; that analogy is reasonable if we adjust the viscosity, temperature, pressure, and time scale from water on the stove to rocks buried deep beneath the surface, but heated from below–just like the pan of water. I’m speculating here but, just to get an idea of what I’m talking about, the crazy structures in Fig. 5A probably took on the order of ten-million years to form.

It might help to see the problem from a more god-like perspective.

As you might expect, the exposure of such a deformed and mineralogically diverse set of lithologies along the Potomac’s course produces features like Great Falls, as well as what we’re examining today.

There is more to these rocks than metamorphic structures, including folding, foliation, and inclusions. All of those were formed between 1000 and 500 million-years ago. After deep burial (maybe 15 miles) beneath an enormous mountain range, these rocks hardened and were exhumed by erosion of the overlying rocks. They were brittle and, as isostatic pressure relaxed, they cracked just like a cooling pumpkin pie, forming joints.

Confused by what I had seen so far (i.e. Figs. 4, 5, and 8), I followed the trail to the confluence of Difficult Run and the Potomac river (Fig. 9).

Looking across Difficult Run to the south at Site 4 (see Fig. 2 for location), I was once again bewildered.

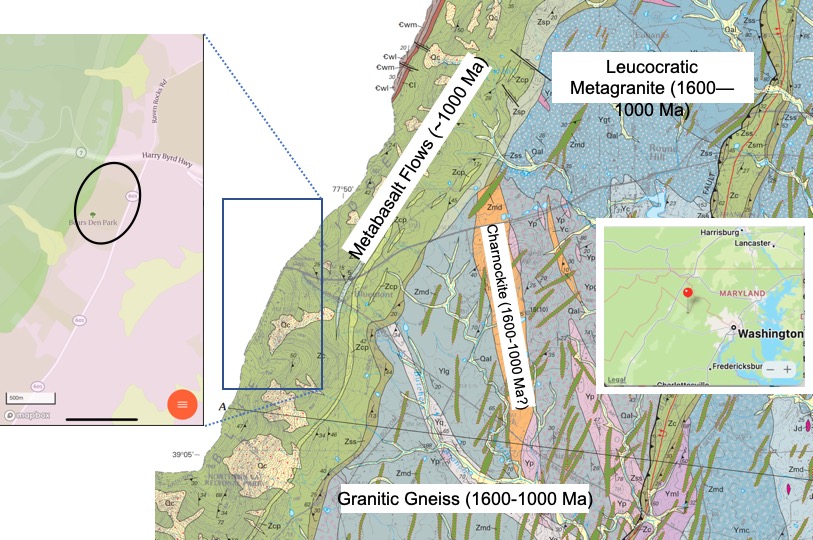

It is tempting to assume that the overlying rocks in Fig. 11 are sedimentary, deposited on an erosional surface in the underlying metamorphic rocks (angular unconformity); however, the geologic map (Fig. 12) reveals that these are similar in age and lithology.

I summarized the geologic history of this area in a previous post, so I’d like to wrap up by demonstrating how pervasive deformation is, in this post. Imagine the deformation seen in Fig. 5A scaled up several orders of magnitude, to the scale of a bluff (Fig. 11). We also saw evidence of rotation of porphyroblasts at another location along the Potomac and again, more than a hundred miles to the south, in Lynchburg. This deformation actually extends to the microscopic scale, but we had neither proper samples nor a microscope to demonstrate it for these rocks.

Think of metamorphosis and ductile deformation as being like a peach pie, the contents trapped between the bottom of the pan (deeper, more resistant rocks) and the pie crust (overburden); the filling is boiling in the oven, overturning, even displacing smaller pieces of fruit. That is what’s happening miles beneath the mountains, on time scales of millions of years rather than minutes.

A Geological Mystery at Bears Den

Beautiful landscapes and geological wonders are never far from your door here in Northern Virginia. Today, we took a hike to meet the Appalachian Trail near the border of West Virginia (Fig. 2).

To reach the Bears Den rest area on the Appalachian Trail (see oval area in Fig. 2), we had to follow a winding path along one of the many irregular crests that define the Blue Ridge Mountains (Fig. 3).

Along the way, we noted that the trail followed the top of a deeply eroded landscape, littered with boulders and weathered rocks (Figs. 4 and 5).

We finally reached the rocky point from which Fig. 1 was photographed. A large outcrop crosscut with veins greeted us (Figs. 6-8).

Intersecting joints like those seen in Figs. 7 and 8 occur when rocks that have been deeply buried are exhumed as overlying rocks erode. The upper mantle relaxes and lifts its overburden in a process called isostatic rebound. Rocks thus uplifted are no longer soft but respond like a solid in brittle deformation. What is intriguing about these rocks (whose age we haven’t yet determined) and the joints that permeate them, is the origin of the quartz and feldspar filling the joints.

It’s time to talk about the host rock seen in Figs. 4-8. The west side of the oval outlined in the inset map of Fig. 2 reveals that these are fluvial-to-shoreface sedimentary rocks deposited between 541 and 511 Ma (source: Rock D lists many sources for this interpretation).

An intrusive magma filled joints (Figs. 7 and 8) and heated the country rock to the point of remineralization (Fig. 9), yet sedimentary textures are retained (Fig. 10). What’s going on?

Summary

There are some general rules in determining relative geologic age. For example, layered rocks are younger as you ascend in a stack of them. This rule applies to both sedimentary and volcanic rocks, although the contacts aren’t as uniform in the latter. Another rule is that rocks that cut through other rocks (i.e. veins and dikes) are younger than the rocks they invade.

The sedimentary host rocks at Bears Den were deposited where rivers fed coastal deltas and a sandy beach (shore face) about 500 million years ago, long after the granites we see to the east (Fig. 2) were intruded and metamorphosed to become metagranites. In other words, the quartz veins and granitic dikes (Figs. 7-12) did not occur when the older (1600-1000 Ma) igneous rocks were emplaced; these veins and felsic intrusions must be associated with the Taconic orogeny, which started about 440 million years ago. The geologic map (Fig. 2) doesn’t show any evidence of granitic intrusions from this period, which could have filled joints created by isostatic rebound in these rocks.

These sedimentary layers were laid down during the collision that created Pangea, so they would have had to be buried deeply enough to become lithified, exhumed to a sufficiently shallow depth to form joints (a sure sign of brittle failure and thus uplift), then invaded by an undisclosed intrusive magma at a very shallow depth (probably less than 5 miles).

Alternatively, they could have remain buried until the breakup of Pangea, beginning in the Triassic period and progressing in stages. Magmatism has been associated with this event in Northern Virginia.

All of this is plausible, given the immense span of time involved, but…

Where are the rocks?

The Race to Ohio

Several of my posts in Northern Virginia have noted the presence of old canals which were part of the earliest transportation system to reach beyond the Atlantic Seaboard (e.g. The Potowmak Canal and Goose Creek canal). Today we crossed the Potomac River and followed the Chesapeake & Ohio Canal for several miles (between Locks 28 and 29), which took us along a scenic path through a metamorphic terrain in Maryland.

The cut for the tunnel (Fig. 1) reveals a dark rock with foliation oriented nearly vertical in the plane of the cut (Fig. 3) with blebs of pink and white material (Fig. 4).

These basalts originally flowed out of fissures and volcanoes, probably at the seafloor, during rifting of a continent (according to Rock-D‘s summary). The origin of magma can be correlated to tectonic regime (e.g., mid-ocean ridge, rifting continent, island arc) based on the chemical signature of the whole rock (not minerals, which are altered during metamorphosis). At any rate, the age range of the Catoctin Formation (1000-541 Ma) spans the final closing of an unnamed ocean to form a hypothesized supercontinent called Rodinia during the Grenville Orogeny between 1100 and 900 Ma — and the subsequent rifting of Rodinia, which occurred between 750 and 633 Ma. Unraveling that time discrepancy is beyond the scope of this blog.

Let’s just say that these basalts (and minor sedimentary rocks) were created during the tumultuous assembly, pleasant life, and violent breakup of a hypothesized supercontinent.

The Catoctin Formation (basalts with some sediments) were buried deeply and metamorphosed by heat and burial pressure but not compressed, at least not enough to produce folds visible at the scales of Figs. 3 through 6. This suggests that Rodinia wasn’t created by huge horizontal forces, crashing tectonic plates together like putty.

Jumping ahead in time to the present, we see these rocks still controlling the Potomac and the development of transportation during the early days of the United States.

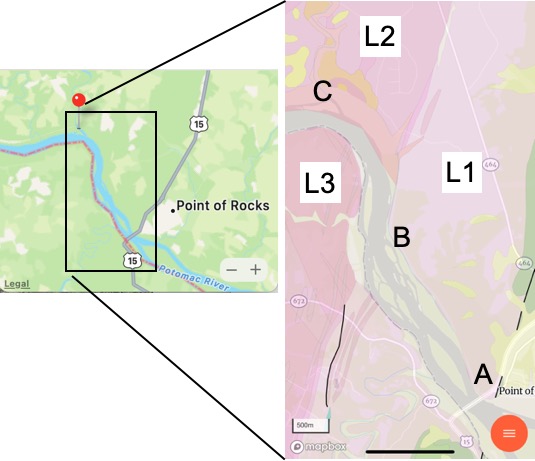

The outcrops seen in Fig. 7 occur very near the contact between the Catoctin Formation and a Pink leuocratic metagranite (1600 – 1000 Ma) with gneissic foliation (L3 in Fig. 2).

It is important to note that the outcrop in Fig. 8 has been exposed to the vagaries of the Potomac since the Pleistocene, so its irregular surface is not unexpected. Nevertheless, the estimated orientation is radically different than that of the Catoctin Fm, which is nearly vertical (see Fig. 6). One possibility is the presence of a fault between the two rock formations, as suggested by the geologic map (Fig. 2). The fault (indicated by the nearly vertical, black line south of Site B) may extend under the alluvial sediments around the Potomac and not be visible in Maryland.

We have one last stop today, Site C (see Fig. 2 for location), where we will try and get some closure on the fate of Rodinia (pun intended).

Let’s take a look at some samples that were conveniently made available by the Maryland DOT, probably during construction of the park.

The rocks we saw today were of similar ages (determined by radiometric dating, not guesswork), and were deposited, deformed, and intruded during the Grenville Orogeny. In other words, based on my brief examination of the literature, these rocks represent the collision of continents to form Rodinia (1100-900 Ma), its long lifespan (900-750 Ma), and its breakup to form the precursor of the Modern Atlantic Ocean (Iapetus) between 750 and 633 Ma.

I’m going out on a limb here (again). It is significant that there aren’t a lot of sedimentary rocks (even metasediments) here, which means they were removed by erosion. Keep that in mind, when I add that even the oldest metamorphic rocks (the granite gneiss, L2) aren’t folded like the schists at Great Falls. These rocks were buried deeply, relative to the impact they survived, which apparently didn’t affect the deeper parts of the crust (at least not along the modern Potomac River). There probably was a lot of folding of the sedimentary rocks that covered these igneous and metamorphic rocks, but they were eroded away during the 150 million years that Rodinia was a (quasi) stable supercontinent. That’s a long time. The youngest of the Catoctin rocks (~540 Ma) were deposited just as the so-called Taconic Orogeny was starting up in modern-day New England…

It is extremely difficult to wrap our minds around such four-dimensional events playing out on such long time scales but, to make it even more fun, the mantle and core are dancing to their own tune and directly influencing everything we experience and can observe from our perilous seat atop the earth’s crust.

Just look at all those canals we dug to avoid the rocks…

Goose Creek

This week we didn’t have to go far to find a quiet place on the Potomac River, its confluence with Goose Creek, where low bluffs of reddish sedimentary rocks watched over the calm water of this sometimes violent tributary (Fig. 1).

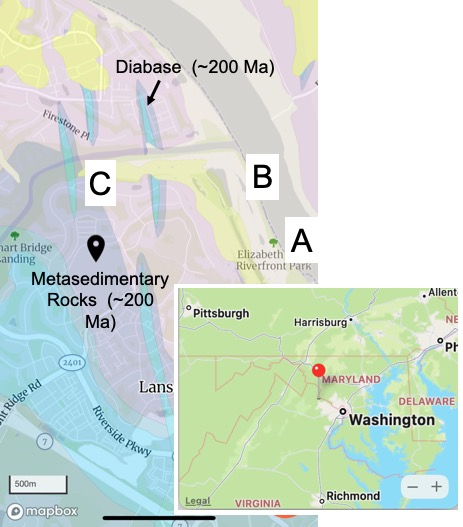

However, things aren’t as geologically simple as the sedate image in Fig. 1 would suggest. This photo was taken within a few hundred feet of the contact with thermally metamorphosed sedimentary rocks that were probably part of the original Balls Bluff Siltstone (Site C in Fig. 2).

We saw diabase in an earlier field trip. Those dikes and sills were part of the same intrusive episode, when North America split away from Europe. Diabase is a fine-grained, intrusive rock with a chemical composition like basalt.

I was unable to measure the orientation of the sedimentary rocks seen in Fig. 1, but my “field estimate” is that they were dipping ~30 degrees away from the camera, with a strike of about (you guessed it) 30 degrees east of north. Such an orientation is consistent with what we saw in a previous post.

The presence of diabase crossing Goose Creek (see Site C in Fig. 2) is indicated by shallow water and a rocky bottom just west of Site C (Fig. 3).

Because of the shallow water over the diabase intrusion in an otherwise navigable stream, a canal was constructed to run from this point downstream to deeper water, parallel to the stream seen in Fig. 2. This was the Goose Creek Canal, finished in 1859 to reach grain mills as far as twelve miles upstream.

Moving back to the Potomac River, there are a few more surprises for us on this field trip (Fig. 8).

This post worked forward in geologic time, in reverse to the counterclockwise path we followed (thin black line seen in Fig. 8). I was surprised to find so much geologic history on a short walk along the shore, surrounded by golf courses and million-dollar houses.

To summarize, as Pangaea began to be torn apart, the mixed sediments of the Balls Bluff Siltstone were deposited in grabens for millions of years, until oceanic crust intruded as diabase dikes and sills, heating these now-deeply buried sediments and altering them into what is called a hornfels metamorphic rock. The rocks we saw today were deposited and thermally metamorphosed between about 237 and 145 Ma (equivalent to millions of years), which is a very long time. But that 88 million-year span was brief compared to the 145 million years that have elapsed since these diabase intrusions forced their way into the picture.

As we’ve seen everywhere along the Potomac, modern fluvial processes are struggling to overcome tectonic events from a bygone era…

Exploring the Potomac: Red Rock and Balls Bluff

Observations at Red Rock Park

I have been exploring the Potomac River from Washington to Harpers Ferry in stages in recent posts. Most of the rocks we’ve seen were Precambrian schists, sedimentary rocks deformed during the closing of the precursor of the modern Atlantic Ocean (The Iapetus). The Potomac River has eroded into the roots of the ancient mountain range that was created by this event, superimposing floodplain processes on these metamorphic rocks. Today I travelled a little further upriver and found different basement rocks, which are the reason I’m excited about today’s post.

Accessing the river at Red Rock park required a short walk along a narrow ridge, left by erosion of gullies into the rocks.

Figure 1 was taken at Red Rock park, after following a steep trail about 100 feet to the river bed (Fig. 3).

A close-up of the outcrop seen in Fig. 1 reveals medium-to-thin bedded, fine-grained sedimentary rock with a reddish hue (thus the name of the park), as seen in Fig. 4.

The sedimentary environment implied by the siltstones and mudstone we see in Figs. 4-6 has (coincidentally) been reproduced today, with weathering of these same rocks and others found further west.

Summary of Red Rock Park

Fine-grained sediments were transported along rivers similar to the modern Potomac about 200 Ma and deposited on a flood plain like we see today. This was when the modern Atlantic Ocean was just beginning to form as the supercontinent Pangea was being torn apart. There would have been mountains much higher than the modern Blue Ridge to the west, and a narrow but widening (~1 inch/year) ocean to the east. Erosion of the ancestral Appalachian Mountains continued for the next 200 Ma, creating thick piles of sediment on the continental shelf of North America, depressing the earth’s crust and burying even terrestrial sediments deep enough to create the Balls Bluff siltstone from mud and silt. As erosion wore these mountains down, the crust rebounded to expose these ancient rocks to the ravages of water and ice. Now, these sedimentary rocks are being eroded as the process continues.

Requiem: Balls Bluff National Battlefield

A little further upstream (see Fig. 2 for location) is the probable type-locale of the Balls Bluff siltstone, but good exposures weren’t accessible because the bluff is higher and the bank narrower, there being no floodplain as we saw elsewhere (Fig. 7). In fact, the only rocks we saw were at the top of Balls Bluff (Fig. 10) and along a trail that led to the river, where I was able to estimate strike and dip.

These rocks contained original sedimentary layering and I was able to estimate that they were dipping to the WNW at about 20 degrees, with a strike similar to the rocks at Red Rock park (i.e. about 30 degrees east of north). This is an important finding, because this is the opposite to what we saw only a few miles downriver. I’ll try and summarize this interesting observation briefly.

Tilting of layered rocks like these siltstones can occur by either folding or faulting. Check out the links to understand these processes. Folding creates great arcs of rock, like sine waves, or ocean waves, as lithified sediments (hard rock) are compressed from both ends. This is what led to the steep folds we saw in the Precambrian rocks at Great Falls and in Lynchburg; our limited observations can’t allow us to decide what happened to these rocks on our own, but we can turn to reliable resources. The sediments that formed the Balls Bluff siltstone have never been compressed; we know this because the Atlantic Ocean is still spreading at a slow and steady rate of about 1 inch/year.

Rocks also become tilted when the earth’s crust is stretched. Even though buried deeply, if they are not in a metamorphic pressure-temperature regime, rocks break and slide around to form faults. This is a well-understood phenomenon that is occurring today in the Basin and Range province of western North America. It doesn’t take much imagination to picture new ocean crust appearing while a continent (Pangea) is being torn apart, snapping rocks buried several miles beneath the surface, like a slab of concrete being removed by a bulldozer.

Crustal stretching produces a series of opposing normal faults that create grabens. These collapsing structures occur at every scale, from outcrops to the birthplace of Humans.

Closing Thoughts

It was good to see some younger rocks, especially Triassic river sediments that are direct evidence for the splitting apart of Pangea. It was a bonus to discover evidence of block-faulting of these same sedimentary rocks after they had been buried several miles beneath the surface. Geological processes occur on time scales of millions of years, with annual displacements of inches or less. Because of the juxtaposition of fast, river-based erosion and deposition and the slow pace of plate-tectonic movements, these rocks record their entire life cycle.

And it continues to this day, as slivers of quartz and oxidized clay minerals are transported yet again towards the same ocean into which they were originally flowing, before being trapped on a primordial floodplain.

Maybe they’ll make it this time…

Update on the Potomac

We returned to Algonkian Park when the Potomac River was running bank-to-bank and about to spill onto its flood plain (Fig. 1).

The water level is several feet higher than on our last visit, and is expected to crest in two days. Unfortunately, I won’t be here to document that event, but I expect the water to be covering the picnic table placed on the active floodplain in Fig. 1. Low areas were inundated (Fig. 2).

Unfortunately, I didn’t take a photo of several large logs resting on the grassy floodplain, deposited by a previous high-water event. Nevertheless, a log can be seen lodged against the bank in Fig. 1, and many more were racing by at 3 feet/second, some more than twenty feet long.

Because of its dynamic height and flow strength, the Potomac is constantly switching from eroding its banks to depositing fine sediment and organic matter on its floodplain. Still, it is downcutting into previous river deposits and spring floods are nothing more than a temporary anomaly in the inexorable transport of sediment from the Blue Ridge Mountains to Chesapeake Bay.

What’s the Difference?

Recent posts have discussed metamorphic rocks found along the banks of the Potomac River in Northern Virginia, buried and deformed during closing of the Iapetus ocean, between 1000 and 500 Ma (million years ago). Those rocks are schist, which formed at depths of about 15 km (10 miles), and temperatures of approximately 500 C (about 1000 F). The original mudstone was ductile under these conditions and the sedimentary layers (bedding) were folded like taffy, while low-melting minerals like quartz were squeezed out and filled cracks and voids, to form veins and irregular, rounded bodies. As extreme as these conditions sound, these are intermediate-grade metamorphic rocks.

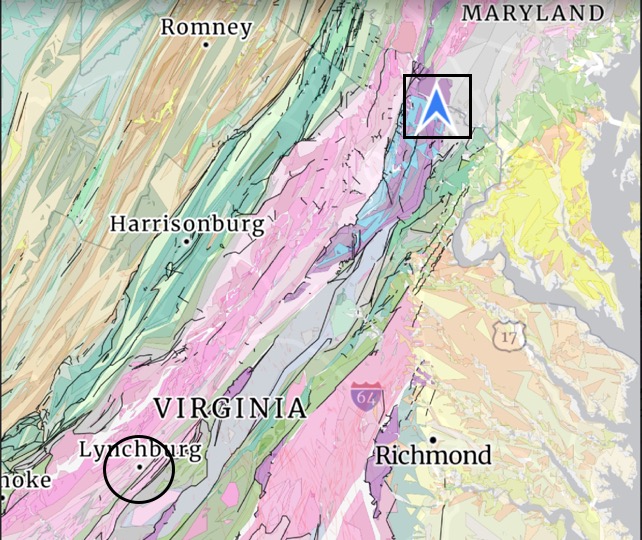

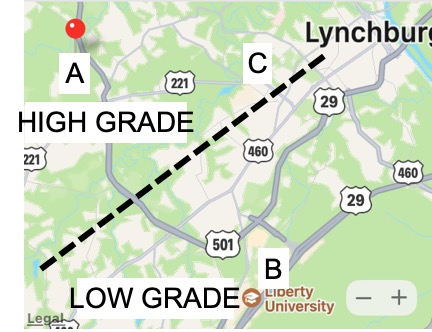

I took a trip to Lynchburg, Virginia (Fig. 1), to see some higher grade metamorphic rocks that were formed at about the same time.

I looked at three exposures of Precambrian rocks on this trip. I would love to show all of the photos I took of the metamorphic and igneous structures I saw, but I will have to restrain myself. (I’ll try anyway…)

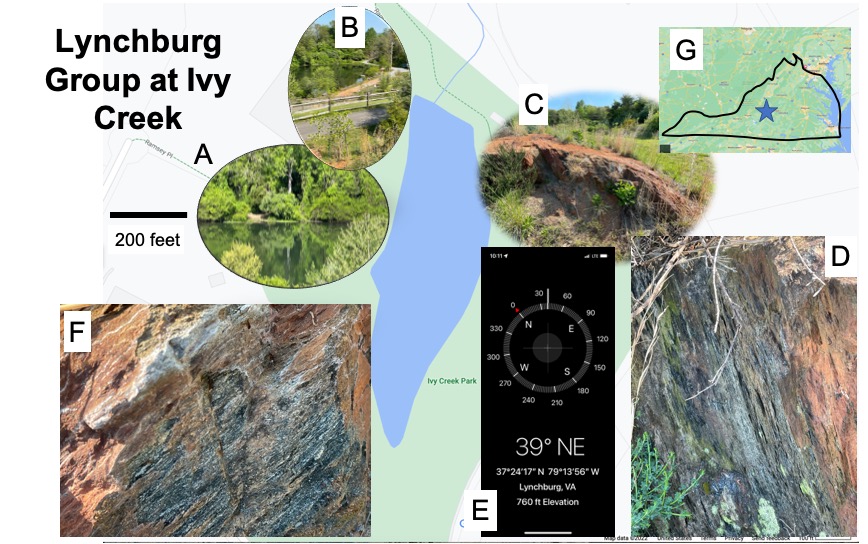

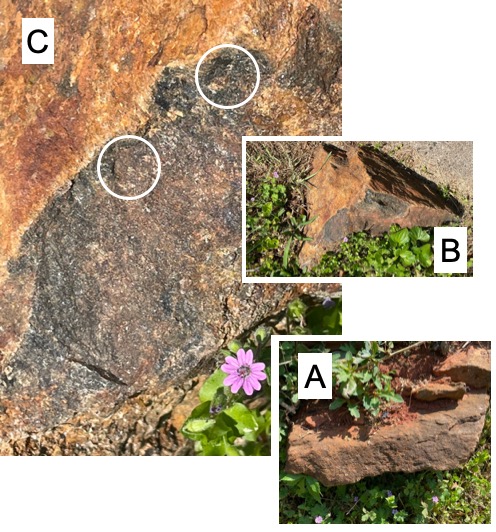

The first locale we visited was Ivy Creek Park (Fig. 2), where there was an exposure of the Lynchburg Group that revealed one of its many facies.

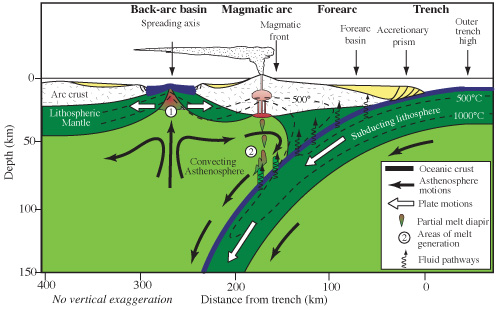

The rocks seen in Fig. 2 (especially Plate F) are probably either biotite schist or graphite schist. Without petrological analyses that are unavailable at this time, there is no way to tell–not that it would matter. The protoliths of these metamorphic rocks were fine-grained sediments, probably deposited in either a back-arc basin or continental subduction zone. They were buried to at least 10 miles and compressed by colliding tectonic plates; however, this small outcrop showed no evidence of ductile deformation (e.g., folds or quartz inclusions). Note that the strike of the foliation in these rocks (Fig. 2E) is consistent with the orientation of geologic trends seen in Fig. 1. So far, so good…

Our next stop took us to Candler Mountain, where a road cut exposed metamorphic rocks for more than 100 m along a narrow road, still part of the Lynchburg Group (Fig. 3).

This exposure revealed many fascinating metamorphic textures–too many to share here. I’m going to focus on extensional features, which might not be expected since I just said that these rocks were deformed during collision of solid land masses, at least island chains like Japan of the Philippines, if not continents.

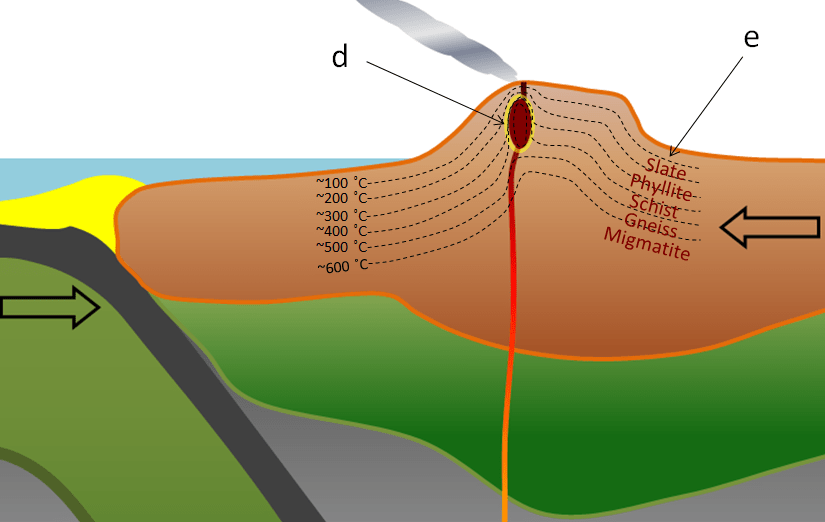

The context for this situation–stretched crust in a tectonic plate collision–is best illustrated in a cartoon (Fig. 4), which shows how the crust can actually stretch to release the stress caused by volcanism, as subducting crust melts under increasing pressure and temperature.

Keeping Fig. 4 in mind, let’s look at the rocks we found on Candler Mountain.

Phyllite is a low-grade metamorphic rock that forms from mud stone at fairly low temperature and pressure (Fig. 6). It is associated with convergent tectonic plate boundaries, and is found in both subduction zones (see Fig. 4) and continental collisions.

Focusing on extensional tectonics for this post, we can see some of the textures we’ve seen elsewhere on Candler Mountain.

The extensional features seen in Figs. 7 and 8 are consistent with these rocks being deformed as suggested in a back-arc basin (Site 1 in Fig. 4) but not buried too deeply (Site e in Fig. 6). However, they are not horizontal, as indicated by the steep dip seen in Fig. 8 (actually they are dipping at more than 60 degrees).

After being heated in the back-arc basin environment, they would have been crushed by the imminent collision of continental land masses, which cannot be subducted because of the low density of the granitic rocks that comprise them. During this compressional stress, they were folded and probably transported many miles along thrust faults, without being buried deeply enough to transform them into schist.

The tilting of these rocks is due to large-scale folding during this later compressional period. The rocks of this area are actually part of an anticlinorium–a region filled with anticlines of every scale, from inches to miles in width. There are a couple of additional superimposed structures I would like to mention before we move on.

There is one more piece of the puzzle that we observed on our field trip. Before we finish with a wave of our hands (and a good bit of conjecture), let’s review.

The dashed line in Fig. 12 is oriented approximately in line with the general lithological trends in Fig. 1, as well as several faults (solid lines in Fig. 1) that have been identified. This line is meant to delineate the schist and phyllite zones (~300 C isotherm in Fig. 6) within a back-arc basin. Schist is high grade. But what do we expect to find at Site C?

The last location we visited was a slope, the edge of a bulldozed lot covered by an apartment complex. None of the rocks we saw were in place, but they hadn’t been moved far, maybe a few yards. We weren’t looking for orientation data, so that wasn’t a problem. What we found was very interesting.

The exposure faced a ravine that had been partly filled to support a road, so we followed the slope until we found more loose boulders with a different lithology.

I cannot say, from the available photographs, which lithology in Fig. 14 is intrusive. However, those details are not the purpose of this post; between the high-grade (schist and gneiss) and low-grade (phyllite) metamorphic rocks we’ve observed, there is a line of intrusive and possibly volcanic rocks with the same general orientation (about 40 degrees east of north). We cannot say anything about post-emplacement deformation of these magmatic rocks, but it is curious that they lie between metamorphic rocks of different grade, in an area with several identified faults (see Fig. 1) having the same orientation.

I have followed one interpretation of the rocks discussed in this post, that they were deposited as muddy sediments about a billion years ago and deformed when volcanic processes stretched the crust. The subduction zone that created this tectonic environment was subsequently caught between opposing continental plates and crushed like a beer can. At some point–probably continuously until the final cataclysm–basaltic magma collected in a subterranean chamber and periodically emerged, creating submarine basaltic flows.

I had a lot of fun with this post (and crushed a few beer cans myself)…

Seneca Regional Park: The Rocks are Awakened

The title of this post refers to the furthest upstream exposure of Precambrian metamorphic rocks (see a previous post) along the Potomac River I have encountered; Precambrian schists rise from the riverbed and surrounding hills, reflecting the plate-tectonic processes that created them, but in a human-friendly form. The perfect harmony of rocks and life is revealed in the mature forests lining the Potomac River (Fig. 1).

I have been reporting on the geology along the Upper Potomac in recent posts (e.g., this post), revealing a braided river that is cutting into flood deposits, until it reaches a bottleneck at Great Falls, where the earth slows the Potomac’s rush to the sea.

This isn’t an overview post, however, so Fig. 2 shows only shows today’s study area. Note that there are three inset maps; the largest (Seneca Park) will be referred to most often in this post.

Starting from the parking lot (P in the Seneca Park inset of Fig. 2), we proceeded towards site A, surrounded by a mature forest (see Fig. 1) established on a thick soil horizon (Fig. 3) that was incised by creeks (runs in NOVA), cut into the regolith surmounting the Precambrian basement rocks (Fig. 4).

The Potomac River at Site A (Dave’s Lookout on Fig. 2) is made up of several islands (Fig. 5) and includes remnants of the Patowmack Canal (Fig. 6), which was part of George Washington’s lifelong dream to make the Potomac River navigable, to open up the frontier as far as Ohio.

The ready supply of fragments of flat rock to construct the canal came from many exposures of the same schist we saw at Great Falls and River Bend Park (1000 to 500 Ma old).

The chemical alteration of the original sedimentary rock (mud deposited more than one-billion years ago) to concentrate quartz (Fig. 8) is evidence of very high temperature and pressure caused by deep burial and deformation during a geological process called metamorphism.

The formation of quartz porphyroblasts within a foliated rock like schist suggests that heat and pressure were distributed irregularly within the study area, melting the silica out of the parent rock but not destroying its original sedimentary layering. This is a fine line that is poorly understood because the extreme temperatures and pressures that produce schist can only be reproduced in the lab at scales less than a millimeter.

Figures 8 and 9 are from the same exposure, taken less than 100 feet apart horizontally, and maybe (I’m guessing) about 30 feet separated them vertically (in their original reference frame). These schists were tilted by normal faults that occurred hundreds of millions of years after deformation, during the breakup of Pangea.

The path took us to Site B (see Fig. 2 for location), along a very shallow channel nearly blocked by a gravel bar (Fig. 10). The Potomac flood plain was wider here but erosion was just as evident as further upstream.

The Potomac’s floodplain is much narrower here than further upstream, as revealed in the topographic map (Fig. 2). Note the number of valleys leading to the Potomac in Seneca Park. However, because of the sudden decrease in channel size, a bottleneck is formed that causes substantial deposition. This created the islands seen in Fig.2 in the past as well as a well-developed flood plain (Fig. 11) characterized by greater foliage than at Horsepen Run. It floods frequently at this bottleneck because the river’s flow is constrained to a narrow and shallow channel as the Potomac approaches Great Falls.

The return to the parking lot (labeled P in Fig. 2) followed a steeper valley lined with outcrops of the same Precambrian schist we saw at Site A, with foliation oriented the same (dipping to the south). The stream followed the rocks (along strike) to the southwest, finding an irregular path around bedrock that surfaced constantly. There were many ledges and dead ends, resulting in shallow pools, along the meandering path the stream had forged in its effort to join the Potomac (Fig. 12).

This was an interesting field trip. We saw how the rocks can rise up from the bowels of the earth to change the character of rivers, where they flow and what they can transport.

Maybe someday we will understand the earth well enough to explain Figs. 5, 10 and 11, using the geological clues presented in Figs. 7-9. The highest mountains and deepest canyons are the result, in large part, to the secrets hidden within the material science of geochemical processes.

Someday we may move mountains…

Geological Bottleneck

Last week’s post showed some of the effects of erosion along the banks of the Potomac River, which flows lazily along a broad floodplain while not becoming so sluggish that it meanders. We know this condition doesn’t last, however, because the broad and anastomosed channels of the Potomac are forced into a narrow throat bordered by immovable Precambrian schist, as we discovered in a previous field trip. Today I am going to approach this series of cataracts from upstream and document the changing river morphology (Fig. 1).

Previous posts have described the floodplain morphology from Algonkian Regional Park (circled area to the upper left of Fig. 1) to the west (upstream), a terrain defined by relict riverbed topography incised by modern stream erosion from the surrounding terraces. At the other extreme, we visited Great Falls in a previous post, where we discovered Precambrian schists that resisted the river’s erosional power.

The field trip began at the Nature Center (black circle at top of Riverbend Park inset map). We followed a trail over poorly sorted gravelly sand (Fig. 2) cut by numerous channels, through what appeared to be a mature and healthy forest. I don’t know what kinds of trees they were but they were at least 80 feet in height.

The assortment of gravel and boulders seen in Fig. 2 is classified as a conglomerate. The rounded boulders and poor sorting suggests that these are fluvial. The boulders became round by rolling along the bottom of the river. This conglomerate (sediment is an unconsolidated rock to a geologist) is matrix supported, which suggests that high-flow events were common, but the majority of the sediment was the product of chemical weathering of rocks like the diabase we saw in a previous post. (Minerals with complex compositions react to water easily, compared to quartz.)

I will return to this later in the post.

However, there were angular pieces of a fissile, dark rock showing up as regolith along the trail (Fig. 3), suggesting that the conglomeratic sediments were a thin veneer over resistant bedrock.

The trail dropped to the river where outcrops of resistant bedrock appeared within the shallow river channel (Fig. 4). This was a substantial change from a few miles upstream

Our path follows the red line along the river bank in the Riverbend inset map of Fig. 2. We are approaching Great Falls. The trail is no longer constructed on conglomerate, but now is traversing sandy silt sediments deposited during the Holocene epoch (Fig. 5).

Schistose rocks with nearly vertical layering appear along the riverbank, and begin to obstruct the trail (Figs. 6 and 7).

Our short hike led to the Aqueduct damn, which supplies water to Washington DC (Fig. 9), where the river transforms into a raging torrent that is challenged only by experienced kayakers.

The transformation of the Potomac, from the placid stream in Fig. 4, to the convoluted and dangerous channel that follows no commonsense rules of river flow seen in Fig. 11, took place in less than two miles (see Fig. 1). I know because I walked the river bank, passing from one era to another before being confronted by a past that will not die…

There is one last point I’d like to make in this post. The imposition of Holocene erosion–streams fed by the Pleistocene highlands bounding the Potomac floodplain–applies here as well as in the gentler topography we saw upstream. The transition from the conglomerate we saw at a major stream draining into the Potomac (Fig. 2) to the more typical fluvial sediment (sand/silt/mud) we found further downstream (Fig. 5) reflects the input of erosion of bedrock only a few miles from the Potomac. This was documented in a previous post, which showed the breakdown of regolith into cobbles, which were transported inexorably to the Potomac.

It is my opinion that this is what has been recorded in the rocks along the banks of the Potomac River, creating the juxtaposition of sediment types along the path of a river that is draining the roots of an ancient mountain range.

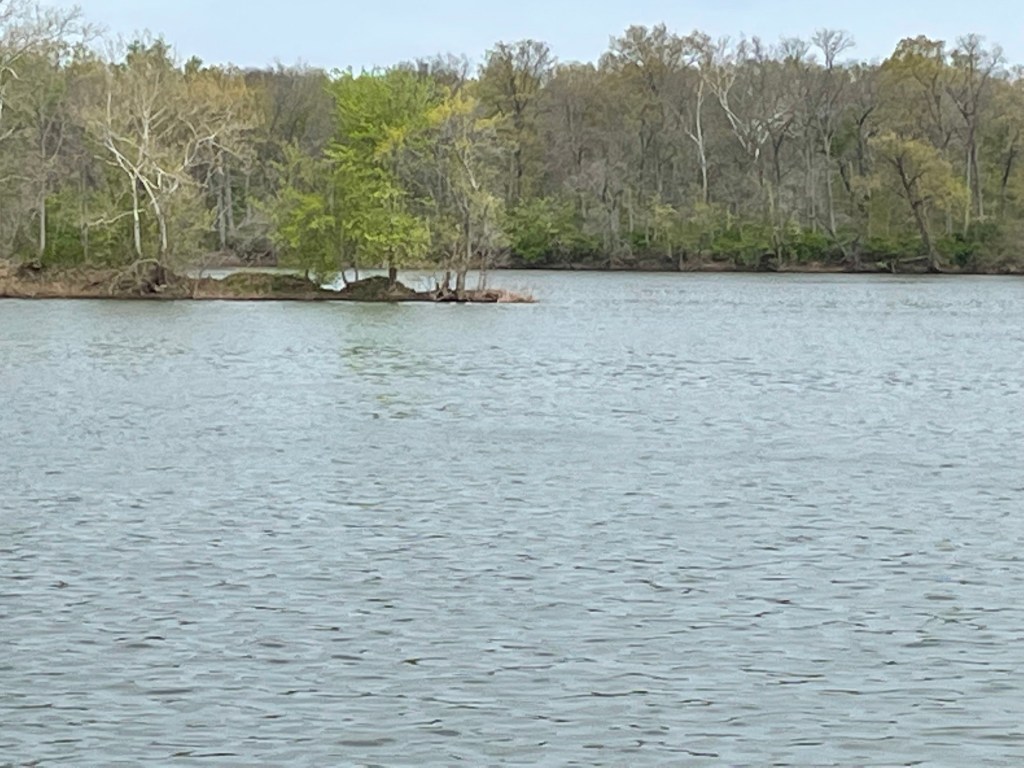

The Dynamic Potomac

This post returns to the Potomac River. We have previously discussed several features along this stretch of the famous waterway: Precambrian metamorphic rocks at Great Falls; sediment contributed by tributaries as well as erosion; and emplacement of intrusive rocks during rifting of Pangea to form the Atlantic Ocean. This time we’ll see evidence of recent erosion, as evidenced in Fig. 1, which shows a large block of stone that has collapsed along the steeply eroded south bank. The bank consists of silt and clay just like further upstream.

Site A (see Fig. 2) is where Fig. 1 was taken. The meandering stream to the east in Fig. 2 is Sugarland Run, which we examined further south, near its headwaters, in a previous post. The Rock-D geologic map suggests that the river is underlain by a Triassic (237-203 Ma) fining-upward sedimentary sequence consisting of sands to shales. A close-up image of the boulder at Site A (Fig. 3), despite a covering of mud and some biological material, reveals no apparent bedding. This is contrary to the description of the Balls Bluff (sedimentary) Member of the Bull Run Formation, contemporaneous with the Newark Supergroup although no longer considered stratigraphically equivalent.

Figure 3 doesn’t look sedimentary to me, but more like the diabase we saw further upstream on Sugarland Run. The streak of white material in the upper-left corner looks like quartz. If these are Triassic sedimentary rocks, they wouldn’t have been metamorphosed, so this exposed block is anomalous. It is possible that this is an outlier of sedimentary rocks that were thermally altered when intrusive rocks were emplaced during Triassic. The area consists of faulted and folded diabase, sedimentary rocks, and metasediments–intruded, deposited or altered, respectively, during the breakup of Pangea during the Triassic period.

The bank is steeply eroded with trees collapsing into the river, indicating rapid lateral erosion during the lifetime of a typical tree (less than a century).

This section of the southern flank of the Potomac River is characterized by a wide floodplain covered with hummocks that represent bars on the original river bed. Superimposed on this older morphology is a natural levee (Fig. 7) that varies in height, steepness, and distance from the modern channel along the river. This landscape has been cut by numerous streams that drain the Pleistocene highlands overlooking the incised river.

Substantial islands (Figs. 5 and 6)divide the Potomac river into two anastomosed channels (see Fig. 2) that have become unstable during the last ten thousand years, as demonstrated by rapid downcutting and lateral instability (Figs. 1 and 4).

Recent Comments