Catoctin Creek: Deep into the Precambrian

Figure 1. The Waterford mill was constructed in the 1820’s and operated until 1939. It was located along Catoctin Creek because there is a significant drop in stream elevation here. A low ridge behind the mill suggests part of the reason: resistant rocks that produce a series of sudden drops in the stream, perfect for collecting water behind a dam not too far from the mill. The shorter the length of the “head race”, the lower the construction costs. The “tail race” can be seen leading from the waterwheel. This small ditch leads around the facility and drains into Catoctin Creek a couple hundred yards downstream. This post will explore upstream on Catoctin Creek, as far as the mill pond (storage pond for hydraulic pressure), and see what the rocks tell us.

Figure 2. (A) Regional map of the study area. My house is labeled with a star. Bull Run fault is a continuous normal fault that we saw at Morven Park and Banshee Reeks Nature Preserve; its location in the figure is approximate. It demarcates younger Mesozoic rocks to the east from older, Precambrian, rocks to the west; the latter form an elongate ridge that cuts through the study area (rectangle centered on Waterford), as well as the Blue Ridge further west, which front the Shenandoah Valley. Vertical movement along Bull Run fault began about 220 Ma (Ma is a million years, but measured by radiometric techniques) when Pangea was torn apart by the newly forming Atlantic Ocean. (B) Geologic map from RockD of Waterford area. The section of Catoctin Creek discussed in this post is enclosed by a blue ellipse. Note that the Precambrian rocks fall into two distinct sequences: 1.6 Ga (billion years measured with radioisotopes) and gneiss, both metamorphosed; and 1 Ga to 600 Ma volcanics and associated sedimentary rocks. The contact between them is an unconformity but the type cannot be determined from field data. This might be a buried and disrupted late Precambrian (~600 my) thrust fault that pushed older rocks over younger, like we saw at Bull Run Nature Preserve.

Figure 3. (A) View looking downstream along Catoctin Creek, showing rounded cobbles (~2 inches) in a sandy matrix, with silt and mud. This unlikely assortment of sediment grain sizes suggests to me that there are multiple sources being mixed along the creek; for example, rounded cobbles suggest miles of transport along swift-flowing creeks whereas mud is the product of physical and chemical weathering of rocks with a small quartz content (quartz is very hard and chemically stable; i.e. sandy beaches). (B) Exposure of older Precambrian schist along the creek bed, forming a low obstruction. (C) The schist layers (schist is a fissile rock) present a weathered appearance; chemical weathering produces mud in-situ without bedload transport, producing few cobbles.

Figure 4. Examples of different rock types found along Catoctin Creek. (A) Collection of angular schist boulders (~one foot in size) at one of the tributaries to the main stream. (B) Quartz intrusion, probably from the oldest rocks (metamorphosed granites and gneisses). The sample is about one foot long. (C) Fresh surface of the schist, showing fissility and a sheen associated with lower-grade metamorphosis, such as in phyllite. This sample was several feet long and had been transported to the mill-pond dam during construction of the mill.

Figure 5. The dam constructed to retain water for Waterford mill contains a variety of large boulders, but the majority were schist (see Fig. 4C). I didn’t see any granite or gneiss, which isn’t surprising because these large stones would have been difficult to transport in the early nineteenth century. They used what was readily available; the exposure of schist along the creek bed (Fig. 3A) suggests that the ridge fronting the mill (Fig. 1) was a likely source of material; after all, rock had to be removed to build the mill and the town of Waterford.

SUMMARY.

More than 1.5 billion years ago, something was happening in Loudon County, Virginia, long before there were multicellular organisms (eukaryotes) or even land plants. There was a collision of tectonic plates massive enough to produce granite and gneiss (high-grade metamorphism) and then deform these very durable rocks.

Four-hundred-million years later, an episode of extreme volcanism occurred and thick sequences of basalt and volcaniclastic sediments were laid down in Loudon County at about the same time (give or take a hundred million years) as deeply buried shales were being transformed into schist at several locations along the eastern margin of modern North America: less than 50 miles from Waterford, at Great Falls; what would become New York City; and Vermont. This was the closing of Iapetus, which took hundreds of millions of years and stretched for thousands of miles, creating Pangea and the rise of eukaryotes, fish, amphibians, reptiles, and mammals, not to mention land plants.

About two-hundred-million years ago, Pangea was torn apart and grabens formed, filling with sediment eroded from the surrounding elevated terrain. These sedimentary rocks are found east of Bull Run fault (Fig. 2A) where they remained protected from the elements (chemical and physical weathering) while the older rocks were elevated to form mountain peaks in the modern world and eroded into boulders, sand, and mud.

Two-hundred-million years later, the shattered remnants of a once-majestic mountain range, stretching from Canada to the Gulf of Mexico, comprise its core of metamorphic and igneous rocks recording events we can only speculate about today.

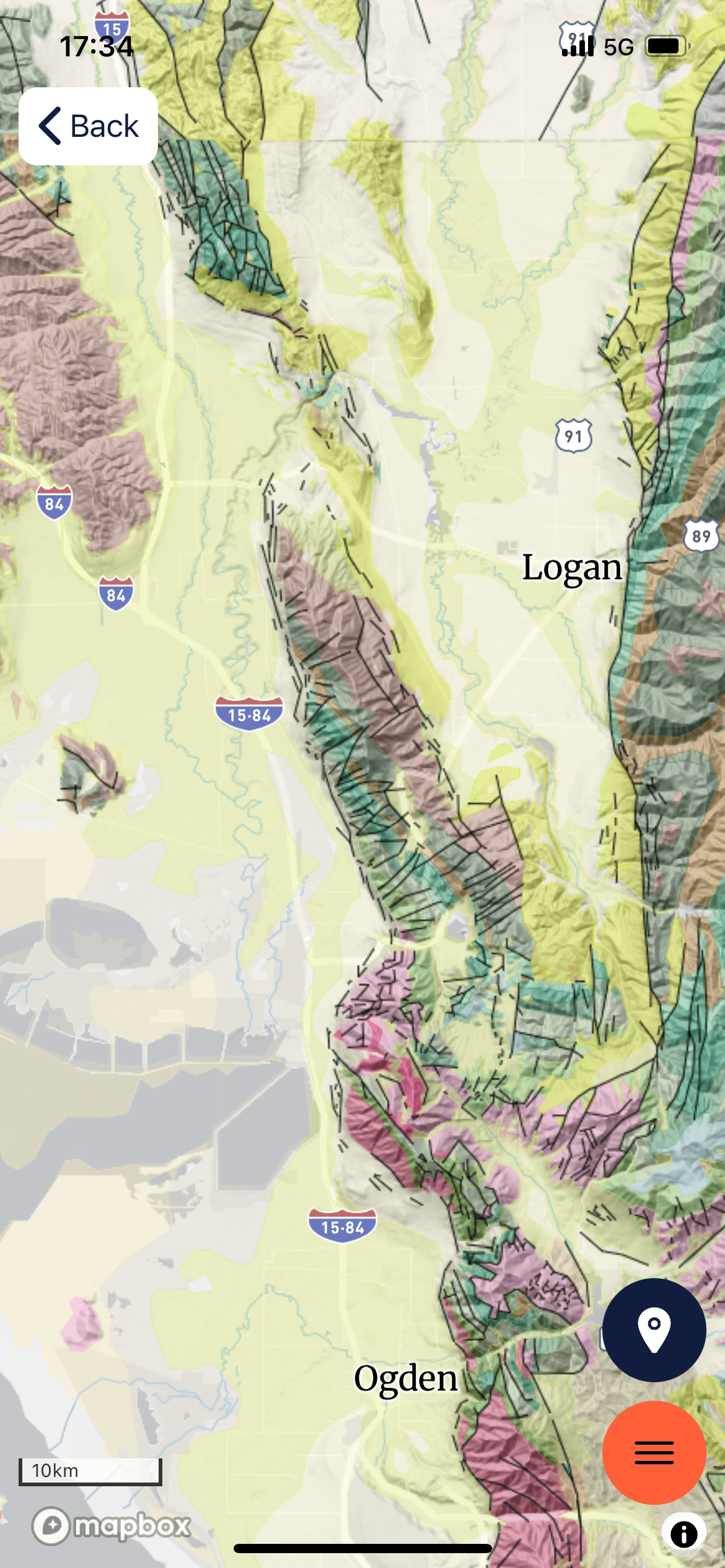

From There to Here: Wyoming

We discussed the tumultuous history of Precambrian rocks in Montana in my last post. The story of crustal shortening in western North America continues to this day. The huge, shield volcanoes comprising the Cascades Mountains show that this westward motion has not ceased at the current time.

The story of oceanic subduction and collision with multiple microcontinents is recorded in the rocks I had to drive past, so I have to resort to a geological map again.

Summary. This was a short post because I was occupied and didn’t have time to explore this fascinating region. Nevertheless, I can confidently say that when Pangea broke up, the North American tectonic plate began to “swallow” the proto-Pacific plate and any microcontinents it harbored.

This 200 my long process created the Rocky Mountains, the overthrust belts of Montana, the Black Hills of South Dakota, the Colorado Plateau, the volcanic Cascade Mountains, the complex system of faults that define California, and so many other geological features of the western North American craton.

It wasn’t as if another gigantic mountain range could form in the aftermath of Pangea’s break-up. The earth can only produce one of them every couple hundred million years, a tectonic pattern called a Wilson Cycle.

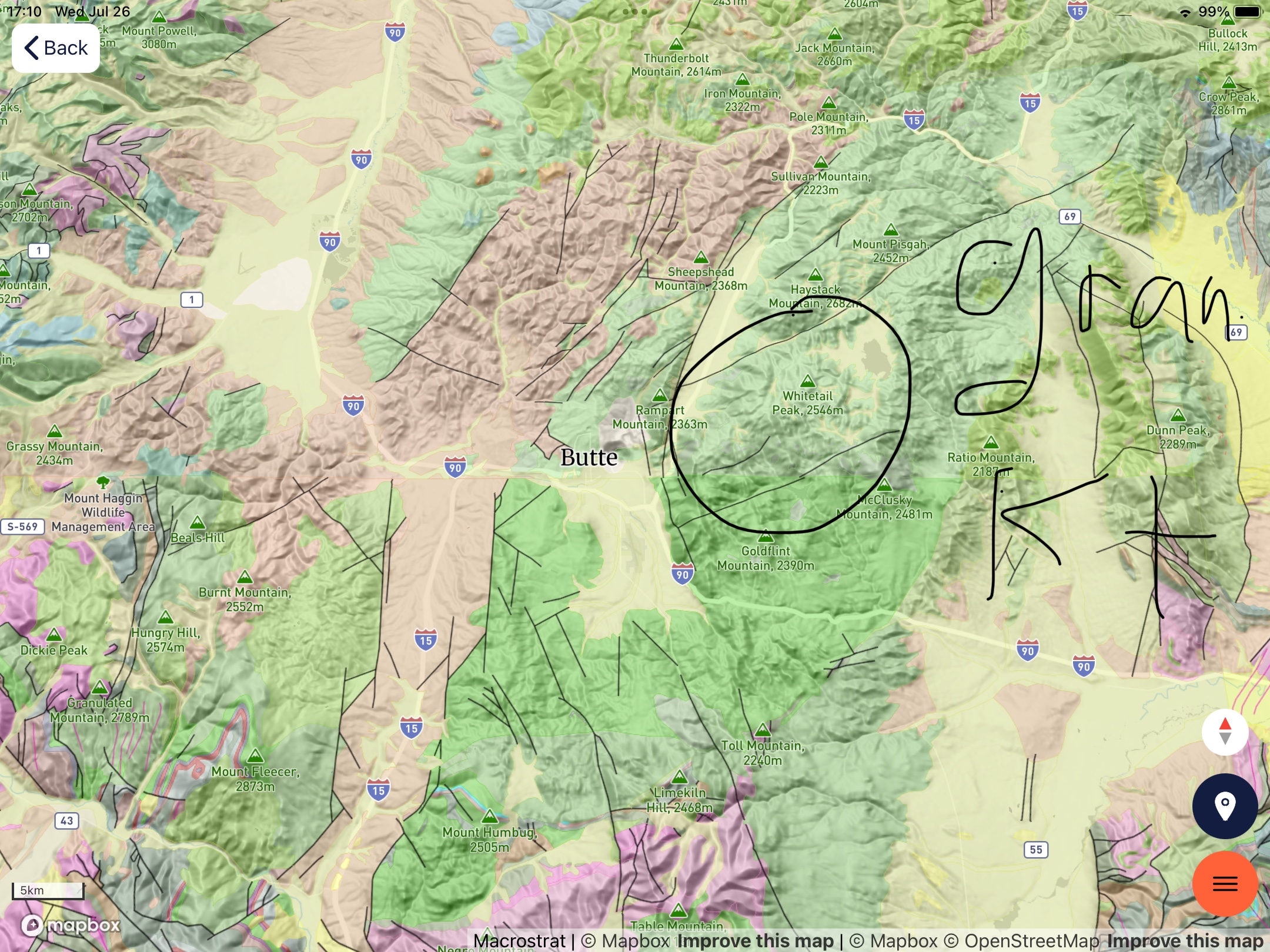

Spokane, Washington, to Gillette, Wyoming: Geology in the Rearview Mirror

This post is experimental and not particularly interesting, but it is the best I can do under the circumstances; I followed Interstate 90 through the Rocky Mountains at 70 mph, with no pull-offs, and trying to take photos in the heavy traffic would have been suicidal. Instead of including a map, photos of outcrops, and some close-ups to examine mineralogy, I am relying on geological maps and my memory. The most experimental part is that I’m working on an iPad, which is a blessing and a curse. Let’s see how it worked out.

Summary. The oldest rocks (Precambrian metasediments shown in purple shades) are scattered throughout the Rocky Mountains. These old rocks were pushed and pulled for hundreds of millions of years as microcontinents collided to form what we call western North America.

Paleozoic rocks (500-230 my) that would have been deposited on top of them, or intruded into them, are only found in scraps here and there (I’m speculating, but Paleozoic rocks have a habit of turning up in the unlikeliest places).

During the late Cretaceous (about 80 my), granitoid intrusions forced their way into these older rocks, as I saw at Butte and other small mountain ranges (pink and tan hues). This was a geologically active period in the evolution of western North America.

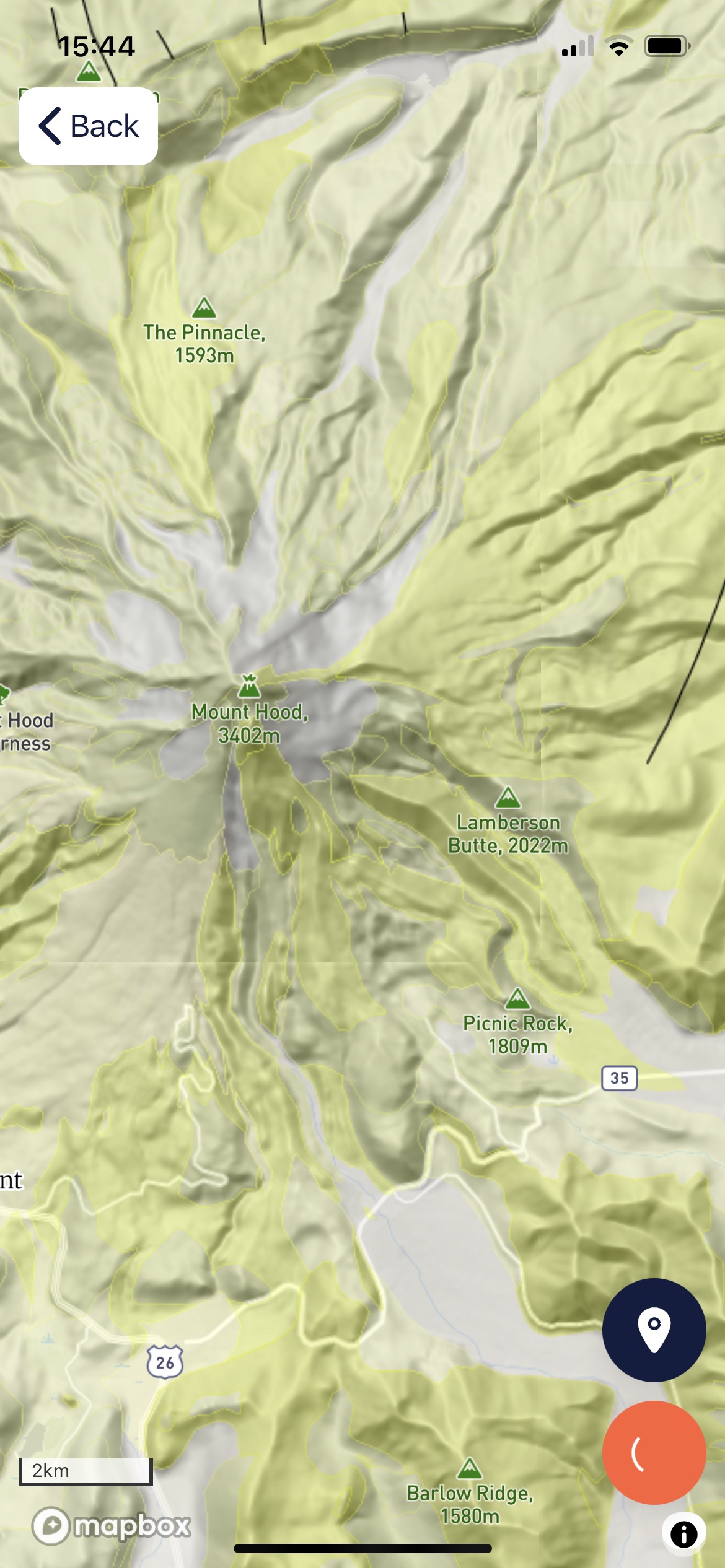

About fifty-million years ago, volcanoes formed along the western margin of North America (e.g. Mt Hood and other volcanoes produced thousands of feet of volcanic rock, forming the Columbia plateau (yellow shades in Fig. 5). At approximately the same time (50 – 5 my) sediment was collecting in lakes and shallow inland seas leftover from the Cretaceous Interior Seaway. These sediments are undeformed and not very well lithified (i.e. not buried deeply); they appear east of Bozeman MT as green in Fig. 5.

Hidden beneath the Precambrian rocks, which were pushed eastward as much as 150 miles in Canada, and Miocene sediments, lay the oil and coal rich Cretaceous sediments laid down between about 150 and 60 my ago. As proof of this, Billings MT (rightmost circled area in Fig. 2), with a population less than 150 thousand, has three oil refineries; but it is so remote, with so little infrastructure (e.g. pipelines), that trucks deliver refined petroleum products to rail cars. It is a modern western boom town.

We’ll see what tomorrow brings …

A question of scale: Indian Canyon Falls

Summary. I found Indian Canyon falls by looking for Lake Missoula park, which turned out to be closed to the public. However, the Park Service supplied a link to other geological attractions, with navigation instructions—GoogleMap took me to a nondescript, heavily wooded area, where I found something I hadn’t expected to see.

The rivulet of water flowing over the “fall” during the dry season is an omen of what is to come for this relatively unknown canyon (it was actually covered with biking and hiking trails). At first the trickle carries only mud, then sand, then gravel, then boulders, then …

Indian Canyon falls is how it begins. Where it ends …

Think big …

Volcaniclastic Deposits at Motel 6

This post is a little weak but I wanted to show that we can find evidence of the earth’s history in our back yard (literally). My interpretation may be completely wrong but it is consistent with my observations and (limited) understanding of volcaniclastic deposits.

I’m going to look at some more curious volcaniclastic deposits tomorrow …

Mount Hood: Volcaniclastic Deposits

Summary. Understanding volcanic stratigraphy is easy with a simple exercise. Spread your left hand out on the table, fingers apart. Each finger is a volcaniclastic flow, either pyroclastic, lava, or a lahar, separated by hundreds of thousands of years. Now, lay your right hand over the left but not with the fingers aligned. Imagine doing this hundreds of times, while peeling away the tops of your fingers randomly (i.e. erosion).

Remember the violent eruption of Mt. St. Helens? It was a pyroclastic eruption (mostly red-hot ash) but what made it destructive was the boiling hot mud encasing boulders of older volcanic material. The blast flattened the trees for miles and the lahar cleaned up the debris.

Imagine such an eruption occurring every year … thank god they are separated by centuries or millennia.

There’s only so much energy available, even for the dynamic earth …

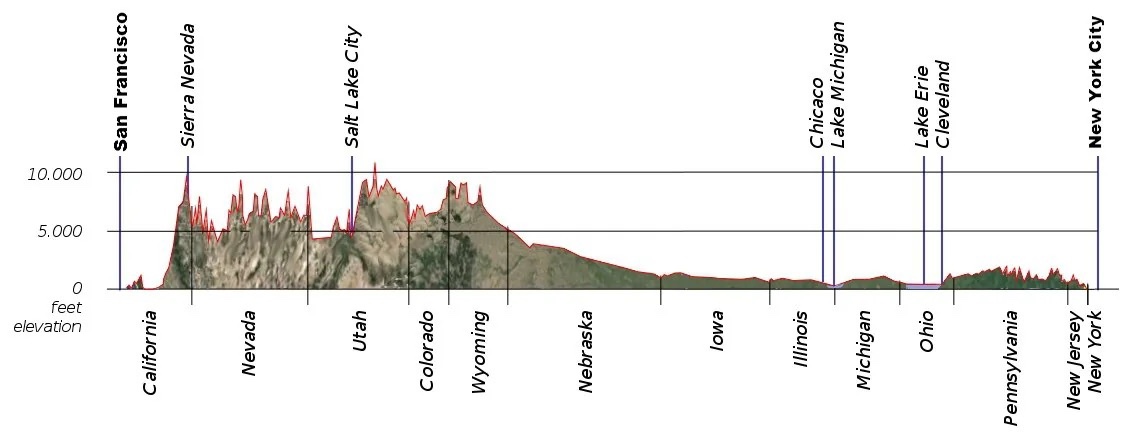

Road Trip Across the U.S.A.

This post is being written in Portland, Oregon, 2800 miles from Northern Virginia, where this journey began. I’m working on an iPad, which is new to me, so I’m going to limit this to a summary of previous posts, and briefly discuss some rocks I haven’t discussed before. I’ll go into more detail on the return trip, which will, however, take a different path.

I have said a lot about the rocks in NOVA (Northern Virginia), so I’ll refer to those posts. The eastern end of Fig. 1 is underlain by rocks more than one billion years old that record a collision on a continental scale.

We also found evidence of deposition in marine and coastal settings throughout the Paleozoic (~500 to 250 my), which I’ve discussed before. This period of erosion was interrupted in the Triassic Period, about 200 my ago, when the east coast began to stretch; coarse sediments filled newly developing basins throughout NOVA.

Our westward journey took us through Maryland and Pennsylvania (see profile above), where we found evidence of broad, shallow seas to the west and rising highlands to the east throughout the Paleozoic.

West of the ancestral Appalachian mountains, from Ohio to Illinois, we saw rolling hills covered with farms that replaced primordial forests. I don’t have any photos of this area, but there isn’t much to see. However, this is where extensive glaciation becomes evident, continuing across the Great Plains to Nebraska. I wrote about the moraines that dominate this region in a previous post.

This post picks up the story in eastern Wyoming (see profile above), where we find sediments deposited in coastal areas during the Late Cretaceous (~100 my) dominating the region.

Figure 2. Geologic map of the area around Rawlins, Wyoming. The majority of the rocks (green hues) are Cretaceous (~145-65 my). Faults (black lines) separate these older nearshore sands and muds from Miocene (~20 my) coarse sediments (yellow colors), Paleozoic marine sediments (aqua tints), and Mesozoic nearshore sediments (blue hues). Note the arch form of the Mesozoic layers; this is an anticline, folded layers of rock, the result of crustal shortening (i.e. compression).

SUMMARY. We started out in NOVA, where a titanic collision occurred more than 500 million years ago. We saw evidence of a similar orogeny in the Precambrian rocks exposed in Utah, Wyoming, and Idaho, long before they were deformed and pushed eastward.

During the Paleozoic era (500 – 230 my), thick layers of sediments were deposited in Pennsylvania (see Fig. 1) as the ancestral Appalachian Mountains rose, then eroded over hundreds of millions of years. The proto-Atlantic Ocean (Iapetus) opened and closed during this immense span of time.

We saw similar Paleozoic sedimentary rocks in Utah and Idaho (no photos available) but the big picture of continuous deposition along huge swaths of what is today western North America is recorded elsewhere (e.g. the Grand Canyon and Colorado Plateau).

The Mesozoic era is mostly recorded in sediments associated with the break-up of Pangea in NOVA, where stretching of the crust produced ridges and intervening grabens filled with coarse sediment. The Mesozoic and Cenozoic eras were spent eroding the ancestral Appalachian mountains as Eurasia and North America went their separate ways.

Vast expanses of shallow marine and lacustrine sediments were deposited in the (modern) central and western United States during the Mesozoic, accompanied by the eastward push of older rocks by episodic collisions; this was not a continental collision but probably a series of micro continents and island arcs being absorbed as oceanic crust was subducted. A vast interior seaway reached from the Gulf of Mexico to the Arctic Circle at this time.

The Cenozoic saw the eruption of vast quantities of volcanic material in Oregon and Idaho as Mt. Hood (and other volcanic centers) reached its peak of activity. The Cretaceous seaway dried up and terrestrial sediments replaced marine deposits, as the Colorado Plateau rose more than 5000 feet, shedding sediments everywhere. Finally, great ice sheets carved the earth’s surface into a new landscape defined by moraines and glacial valleys.

The Cenozoic is mostly under represented in NOVA because sediment collected on the continental shelf of North America, which was (and still is) a passive margin. Everything that was carried westward by the Mississippi River system was deposited ultimately in the Gulf of Mexico, where huge oil and gas fields developed from organic material transported by an ancestral Mississippi River drainage system. There was no room for sediment as the Appalachian mountains rose, in response to the removal of miles of overlying rock.

This has been a brief and probably inaccurate comparison and contrast of eastern and western geology of the United States, but it is only what I’ve seen with my own eyes, enhanced by the vast knowledge accumulated by generations of geologists tying the story together.

We’ll see what I learn on the return journey …

Galway … and Beyond

Figure 1. This photo shows the post-glacial, Pleistocene surface of the Carboniferous (320-300 Ma) limestone we’ve seen throughout Southern Ireland. The paucity of stone walls in the area suggests that boulders deposited by a glacier were less common here; the absence of drumlins or moraines further suggests that this area was scraped clean of loose material before the glacier retreated for the last time about 20 thousand years ago.

Figure 2. These layers of limestone are dipping at less than 20 degrees (field guesstimate), revealing different strata within the section. Low hills within the area indicated by a pin in the inset map of Fig. 1 were constructed of such tilted strata.

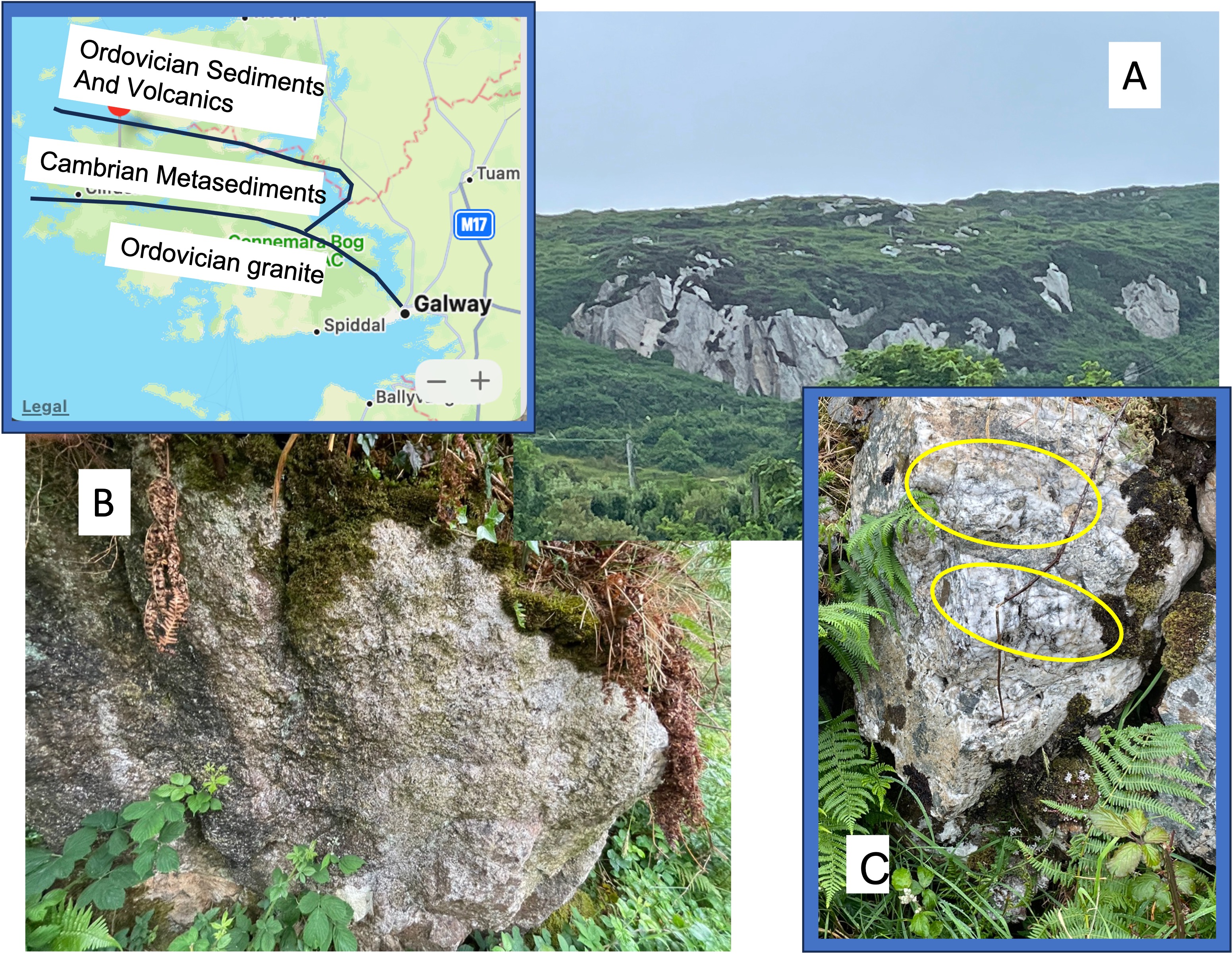

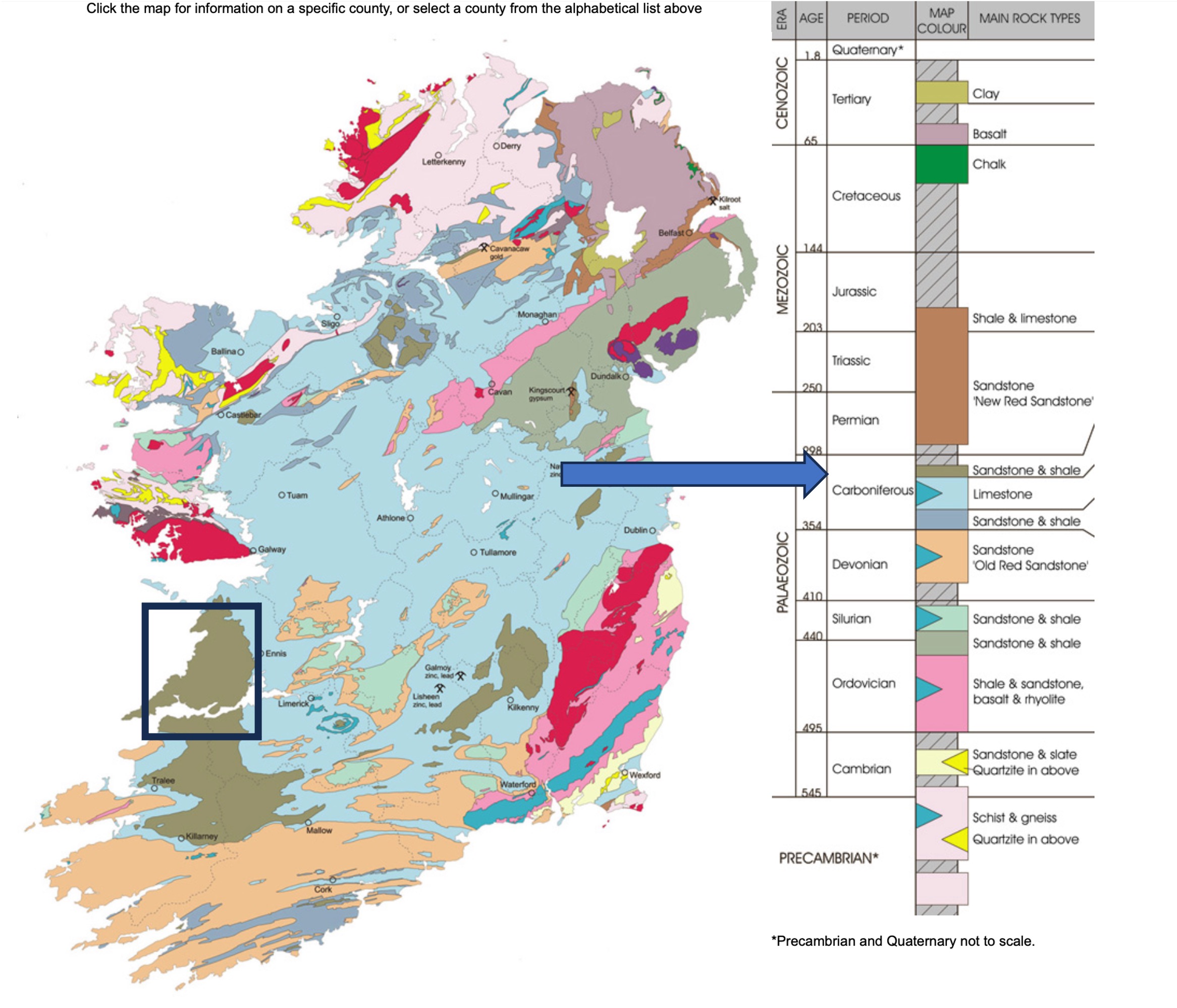

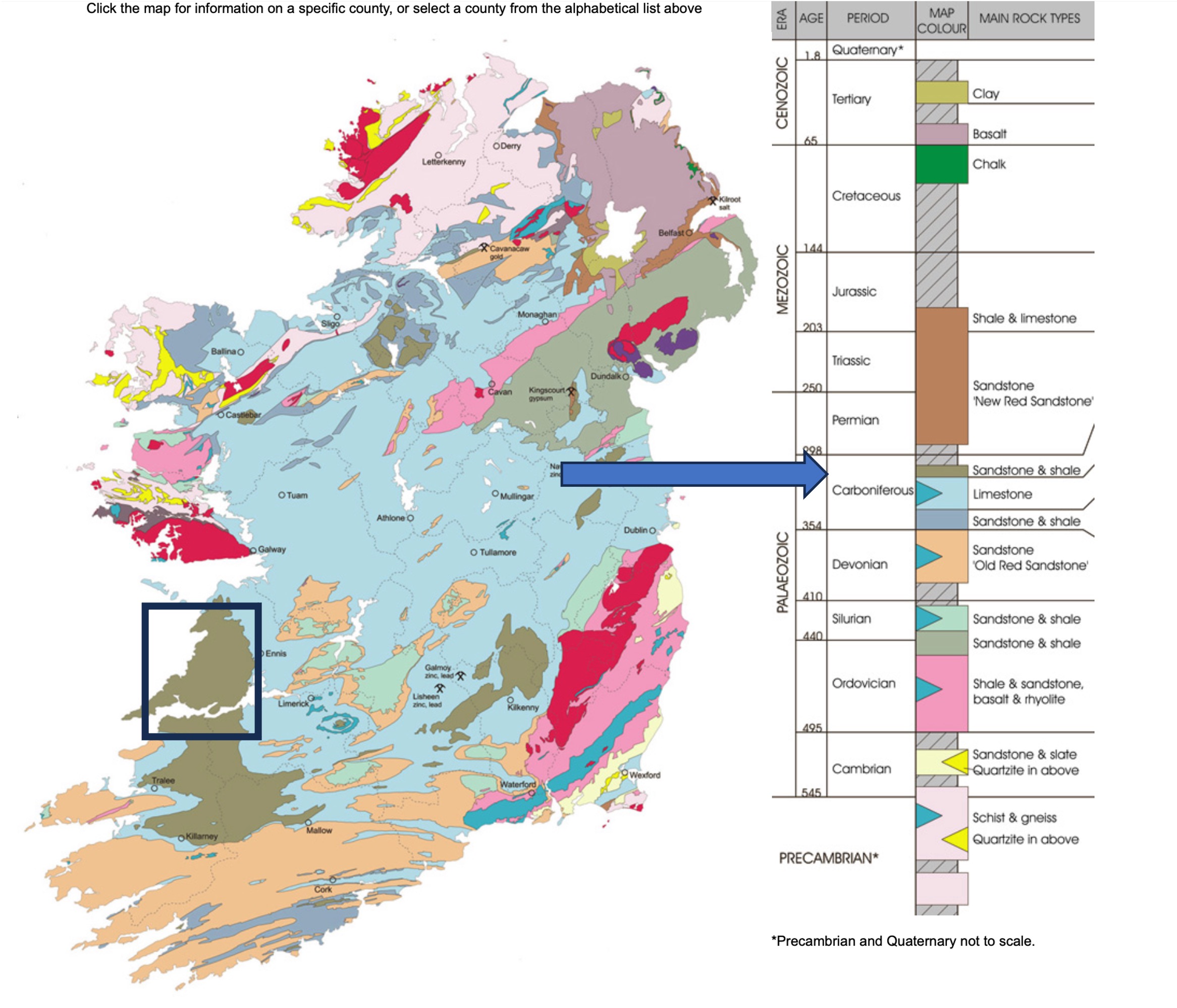

Figure 3. Geologic map of Ireland with the region discussed in this post highlighted by a black rectangle. The blue areas are the limestones we’ve seen before, indicated in the stratigraphic column (right of figure) with a matching arrow. These are the youngest rocks in this area. The pink area at the top of the study area is Ordovician (gray arrow in stratigraphic column), between 495 and 440 million-years old; these sedimentary and volcanic rocks are much older than the limestone. We’ll be focusing on Cambrian (545-495 Ma) sandstones that have been metamorphosed after burial and heating. This is the yellow-shaded area on the map and stratigraphic column. These are the oldest rocks we’ve seen in Ireland. Note the red area, and arrow in the lower map key (igneous rocks are shown separately in this map). These are Ordovician in age and thus much younger than the metasediments we’ll be looking at in this post.

Figure 4. The inset map focuses on the upper-left portion of the inset map in Fig. 3. The three main rock types introduced above are labeled for clarity; note the presence of older (Cambrian) metasediments sandwiched between intrusive granite and sedimentary and volcanic rocks of Ordovician age. This curious stratigraphic relationship is due to an orogeny that occurred during the Ordovician geologic period. Cambrian sediments, mostly sand and shale, were buried several miles beneath the surface, when even deeper rocks melted to form magma, which rose as granite. The sediments were heated under moderate pressure, and then injected with fluids from the magma. The Ordovician sediments were deposited during this orogeny but were not buried as deeply as the subjacent Cambrian rocks.

Plate A shows a typical exposure of the Cambrian metasediments. Note the general appearance of a bedding plane, tilted steeply, facing towards the camera. Plate B is a boulder (possibly loose) of weathered meta-sandstone that reveals a dense area (lower right of outcrop) and indistinct bedding with resistant grains (probably quartz) set in a weathered matrix of darker material. Plate C, a photo taken less than a mile from Plate B, shows a small boulder comprising mixed grain sizes, with quartz inclusions (circled in yellow). The heterogeneity of this sample indicates that these sediments weren’t buried deeply enough for recrystallization to occur AND they were close enough to the magma to be injected with fluids .

These samples were observed near the boundary with the Ordovician granite (see inset map). These same sediments look very different further from the granitic intrusion.

Figure 5. Photo of the Cambrian metasediments further from the boundary with the Ordovician granite. The topography here (see inset map of Fig. 4) consists of a series of high, steep mountains comprising these resistant rocks.

Figure 6. Images of outcrops (in-place rock) away from the intrusive contact zone. (A) This photo (two-feet across) shows nearly vertical bedding planes, indicated by a yellow line. Note the uniform surface of this quartzite, which retains original bedding, as shown by dark laminae. (B) This photo shows a contact (yellow line) between the quartzite and a dark rock, which cuts across sediment layers (horizontal in the photo). This stratigraphic enigma may be caused by differential weathering along a fracture, long after deposition and subsequent deformation. (C) This close-up (photo is two-feet across) shows quartz veins dispersed within quartzite.

Let’s quickly return to the inset map of Fig. 4. Now that we know that the sedimentary layers were tilted almost 90 degrees during a mountain-building period, it makes sense that the Cambrian sediments are juxtaposed between younger rocks; they were intruded by granite, while younger sediments were deposited on top of them. These older rocks were heated to a higher temperature by contact metamorphism, and injected with magmatic fluids.

Figure 7. This figure shows a high-resolution image (inset) of the area we discussed in this post. The lower part of the map coincides with the Ordovician granite and the upper part reflects glacial carving of the Cambrian metasediments. Granite weathers much faster than quartzite and is less resistant to physical erosion; thus, the bogs we encountered on our drive are located to the south. This weathering occurred after all of these rocks were tilted during the Paleozoic, and uplifted during the Mesozoic; but before glaciers moved southward (black arrow), forming steep hillsides devoid of soil and trees, during the Pleistocene. That’s a time span of 200 million years.

Summary. Mountain building in Northern Virginia was active between 1000 and 500 Ma. Erosion has removed all geological evidence from the rocks I’ve seen in Virginia, until 200 Ma, when Pangea was torn apart; and North America and Europe were created.

About 550 Ma, sandy sediment was being deposited in shallow seas of Southern Ireland, continuing for at least 100 million years while magma collected in the shallow crust, producing granite intrusions for another hundred-million years. During this dark age in Virginia, the mountains grew then eroded in Ireland and a shallow sea formed, filling with sand, silt, and mud; the shells of marine invertebrates collected in this now-quiet marine environment.

Glaciers never reached Virginia but they covered Ireland throughout the Pleistocene, transforming its landscape.

That’s it in a nutshell …

So far.

The Big Picture: Moher Cliffs

This is a famous photo (taken by me) of the Moher Cliffs that reveals the Late Carboniferous (320-300 Ma) mud/silt/sand stone we saw at Foynes and again at Kilkee. The silt/sand layers are thinner at the bottom of the cliff (white accentuates them) and thicker towards the upper parts. This pattern suggests a transition to shallower water, from turbidites and other delta-front sand deposits, to massive nearshore submarine bars. The land was rising relative to the sea.

These layers of sedimentary rock are flat while gently dipping to the south, unlike the steeply tilted strata at Foynes, or the undulating rocks at Kilkee. The delta system represented by these rocks was extensive and not subjected to major deformation during the collision of tectonic plates that created Pangea.

This figure shows the geology of Ireland with the delta sequence colored in brown. Note its extent south from the rectangle that includes the locations discussed in this and previous posts. This area was a delta several hundred miles in extent, about 310 million years ago. The green rocks that cover most of Ireland are the same ones we saw before, and will see again. These limestones were deposited in the extensive, shallow sea that waited for the imminent collision.

My next post will look at the red area on the map, due north of the rectangle, as well as the glacial topography that defines Ireland today.

Kilkee Cliffs: A Closer Look at Late Carboniferous Delta Sediments

Figure 1. Wide view of the area called Kilkee Cliffs, showing the nearly horizontal bedding plane of these Late Carboniferous (about 310 Ma) rocks. Note the slight dip towards the right (northeast) of the cliff in the distance. These are the same rocks I saw at Foynes.

Figure 2. Geologic map of Ireland, showing the area reported on today and in the next post, colored brown and offset with a black rectangle. The view in Fig. 1 is looking to the northwest near the center of the rectangle. The stratigraphy of Ireland is shown on the right, with the arrow indicating where these rocks fall within the sequence that has been identified in Ireland. The limestones I reported on earlier are just below these rocks in the stratigraphic column.

Figure 3. These rocks comprise thin beds of sandstone and shale towards the top of this image, and thicker beds of sandstone and siltstone lower in the section. These rocks have been identified as turbidites and delta sediments. I discussed this in the previous post.

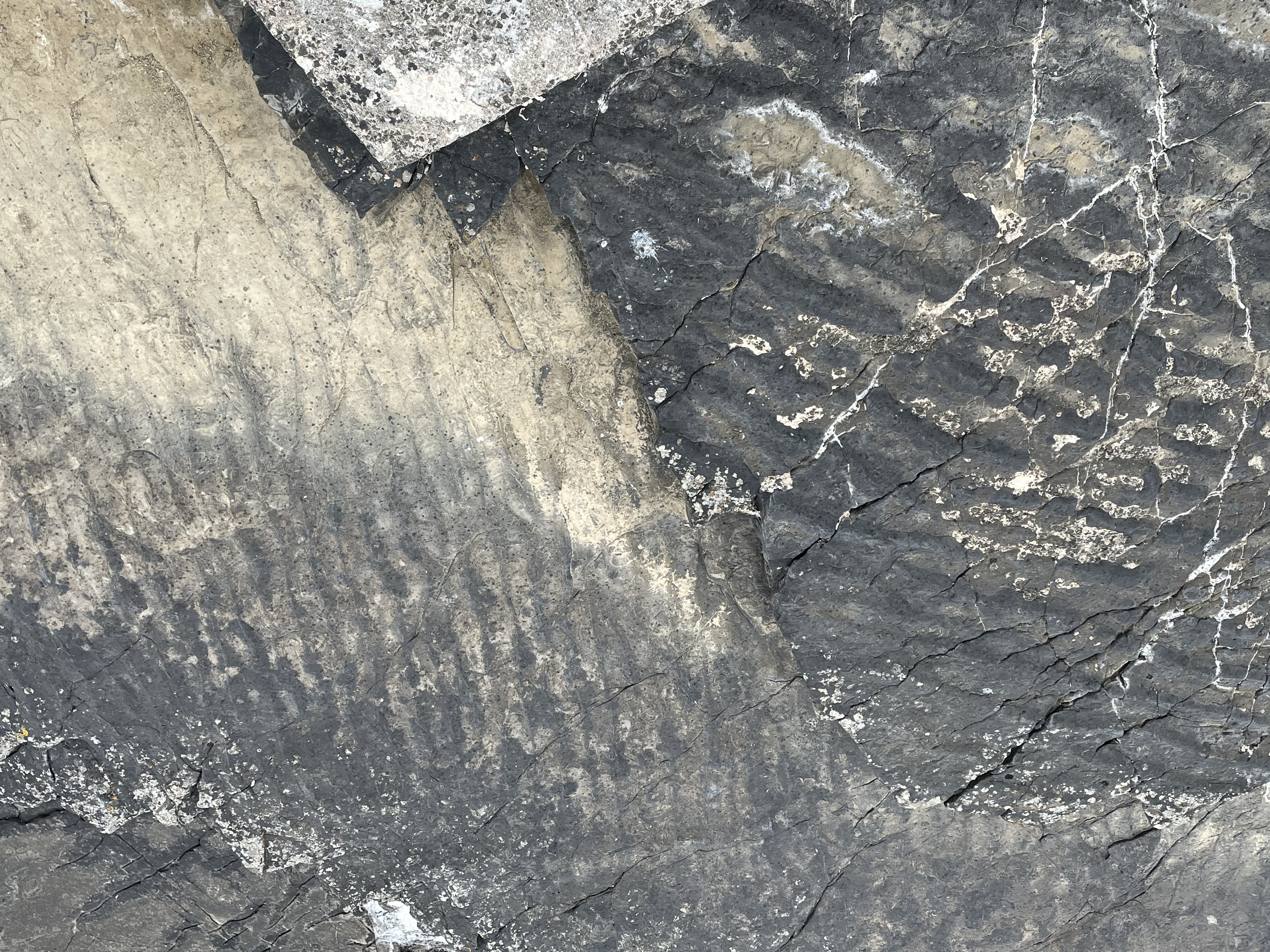

Figure 4. Close-up of a bedding plane within the thin beds shown in Fig. 3. The surface is covered with elongate ripples in the background, and more lunate ripples towards the lower-right. These ripple marks are more common in a nearshore environment (e.g. water shallower than 100 feet) than in turbidity flows, which are not as spatially uniform.

Figure 5. Detail of wave ripple marks. The water depth of the silty sediment in which they formed depends on several factors: grain size, surface wave properties (e.g. wave height and period), water depth; thus, the exact water depth cannot be determined. However, if these ripples were buried by a sudden influx of sand/silt during a storm, the water would have been deeper than if the waves were fair-weather and the silt/sand was introduced by a river flood.

Figure 6. This image (looking down) shows ripple marks on bedding planes less than six inches apart vertically, in sediment deposited within months. The upper ripple marks (finer and more continuous) indicate waves arriving from the left of the photo; the lower (darker and larger) ripple marks suggest waves coming from the top of the photo. If I had to guess, I’d say that the older ripples were formed during a storm (i.e. larger waves produce larger and more irregular sand ripples); the younger set (buried within a few months) suggest quieter conditions. We don’t see details of past environments preserved much better than this.

Figure 7. This photo shows a set of uniform joints as X’s in the center of the image. They are very dense and form right angles. Sets of these joints occurred about 20 feet apart. These sets of joints were aligned with fracturing and preferential erosion along lines oriented from the top to bottom of this photo; the ‘V’ at the top of the image is the seaward extension of one such set of joints; the white patch in the upper-center shows where a layer has spalled off. The same delamination can be seen in the foreground. Imagine layers of paper being folded slightly; they slip against each other. The rock seen in this photo did that and, because it was no longer soft from burial and geothermal heating, it fractured on the outside of bends as the layers slipped.

Figure 8. This photo (image width is about two inches) shows crystals filling some of the joints as seen in Fig. 7; this could be quartz or calcite, but the orientation of the crystals’ long axes at an angle to the joint margins suggests that they formed during slippage, i.e. as the layers were sliding past each other. This is probably calcite, which precipitates readily from ground water (e.g. stalactites in caves) whereas hydrothermal fluids rich in quartz are rare without a nearby source of magma. There is no evidence of that in this region at this time.

These rocks weren’t folded or faulted as we would expect if this area was compressed during collision of the porto-North American and porto-European tectonic plates during the Paleozoic era. Maybe these sediments were deposited when mountains were uplifted during that ancient orogeny.

As I said before, mountains are as often as not identified by their erosional remains rather than their cores …

Recent Comments