Jurassic Diabase Exposed by Drought!

Plate 1. View looking south from the northern end of Beaver Dam reservoir, which serves as a secondary water reserve for Loudon County, Virginia. According to signs posted around the shore, it was drained for maintenance. This photo shows an outcrop of Jurassic diabase that is unusually leucocratic (light colored minerals).

Plate 2. Geologic map of the area around Beaver Dam Reservoir. The outcrop seen in Plate 1 is a high-titanium, quartz-normative tholeiitic diabase, which occurs in dikes and differentiated sheets throughout the map area labeled as Jdh on the map (Jurassic age). The high titanium content and available quartz indicate that this intrusive rock originated within a larger magma chamber (deeper within the crust) and multiple intrusions were emplaced over a period of time as the chemistry evolved. Tholeiitic magma is associated with mid-ocean ridges, which indicates a mantle source rather than melted crustal rocks. A different diabase (Jdg on the map) is younger and was injected into the pre-existing diabase (Jdg) as granophyre, an intrusive rock that indicates a highly evolved magma chamber. These intrusive rocks were injected along bedding planes, faults, and fractures within the Jurassic-Triassic Bull Run Siltstone (JTrtm on the map). Two other Jurassic diabase units (Jdl and Jd) are indicated by circled areas where they cut across Triassic sedimentary rocks (lower area where Jd cuts JTrtm) and Jurassic diabase (upper circled area where Jdl cuts Jdh).

Plate 3. View of the reservoir showing the man-made shoreline and boulders scattered on a sandy-muddy substrate. The title of this post is intended as geological humor disguised as a newspaper headline. I wondered why the reservoir was so low.

Plate 4. This image (approximately 2 feet across) reveals a medium-sized crystalline texture and color similar to granite, which was the initial field identification. An important difference between these rocks and granite is the lower quartz and alkali feldspar content, which isn’t visible in this exposure. Note at least one set of joints, indicated by the weathered “X” rotated slightly to the left, in the center of the photo; then let your eye go down a little and you will notice another X, this time rotated to the right. This second X is repeated throughout the exposure. This type of joint is associated with fracturing of the rock as it cools and pressure is reduced because of erosion of overlying rocks. The suggestion of multiple patterns (I admit it isn’t that obvious) implies several steps in cooling; however, interpreting joints is complex, requiring many detailed measurements, and beyond this post. I just wanted to mention it because joints tell us about the geologic history of a rock after its formation, millions of years later.

Plate 5. This photo shows a large outcrop at the high-water mark of the reservoir. Note the angular structure of the outcrop (lighter rock at the upper left of the image) and the pieces broken off during construction of the reservoir.

Plate 6. View looking north towards the outflow gate of Beaver Dam reservoir, showing the weirs and maximum water level (about fifteen feet above present level). The low water level suggests that evaporation and ground-seepage (not much with the subsurface comprising diabase) exceed local run-off. This is the reason for the post title. Rainfall has been low enough that the water level keeps dropping, even after the reservoir was emptied. Is it a drought?

The last post reported a generic Jurassic diabase (Jd) west of the Bull Run fault (BRF), less than 10 miles NNW of Beaver Dam reservoir, which was intruded into Precambrian sediments. However, Jd also occurs as small intrusions throughout Loudon County (not shown). In other words, it wasn’t emplaced as sills or sheets, but rather filled fault and other fractures in older rocks. Using general principles of stratigraphy (e.g. Steno’s Laws), we can speculate about what we’ve seen in these two recent field trips.

The unspecified Jurassic diabase dike we saw at Morven Park (Jd in Plate 1 of the last post) cuts through Proterozoic sediments but wasn’t seen east of Bull Run fault in that area. The younger (Triassic) sedimentary rocks in the area of Beaver Dam reservoir (JTrtm in Plate 2), as well as Jurassic intrusive rocks (e.g. Jdh on Plate 2) are cut by dikes of diabase (Jd and Jdl, circled areas in Plate 2) that suggest the continuous chemical fractionation of a magma chamber, which produced smaller amounts of magma that had less space to fill.

I propose that magma with a composition like most of the world’s ocean floor formed (tholeiitic basalt, or Mid-Ocean-Ridge Basalt–MORB) beneath the oldest rocks in the area (more than 500 million years old) when Pangea was stretched by upper mantle convection during the early Jurassic (about 200 million years ago), sending tentacles of molten rock to fill every weak point in the overlying rock, sheets and dikes were created, possibly even laccoliths, between layers of sediments. This stage created the large area of diabase in the study area (Jdh in Plate 2). As the magma chamber lost material and cooled, it injected smaller volumes of magma into even smaller fissures and weak points in the overlying rock, including earlier diabase. These late-stage injections are seen as dikes of Jd and Jdl in Plate 2.

Finally, the crust throughout this area stretched to the breaking point and Bull Run fault formed, with the east side sliding downward and to the east. All of the Paleozoic and Mesozoic rocks on the west side of Bull run fault, including diabase sills and dikes, were eroded by wind, water, and ice, leaving only the final, highly fractionated late-stage magmatic dikes (e.g. the granophyre of Plate 2) protruding out of the Precambrian sediments. The deep source of all of these diabase plutonic rocks remains buried deep beneath western Loudon County.

Finally … the only Jurassic diabase I found on the USGS geologic map of Loudon County occurs as thin exposures parallel to Bull Run fault and within a mile of it, which suggests that BRF defines the western limit of the fault zone associated with the break-up of Pangea.

That’s my story and I’m sticking to it …

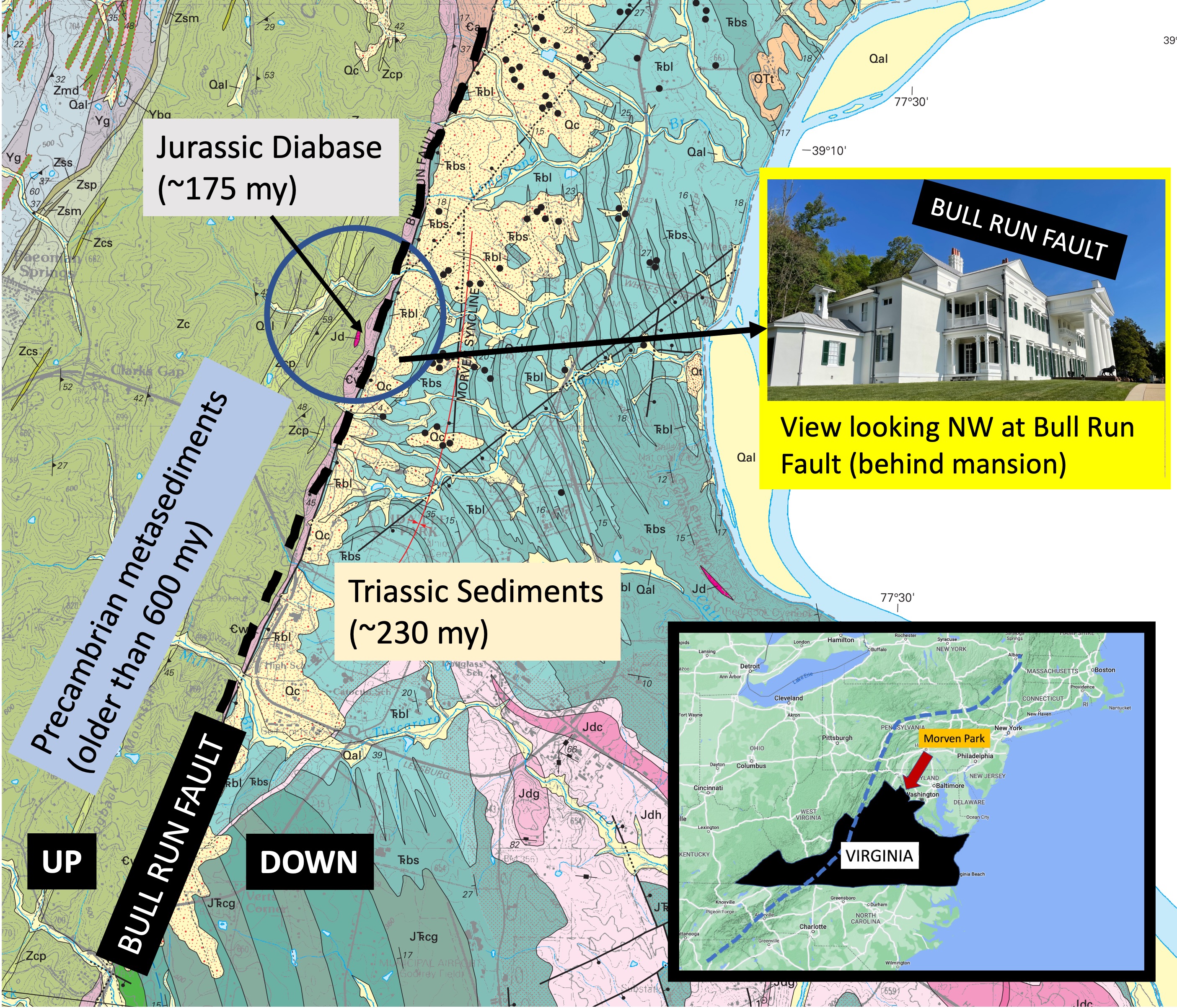

Morven Park: Making and Breaking Pangea

Plate 1. Geologic map of study area in northern Virginia (see inset map). The area is bisected by the Bull Run Fault (BRF, dash line), which separates older metasedimentary rocks from younger sedimentary rocks. The west side of BRF has moved upward relative to the east side, following the regional trend along the east coast of North America (dash line in inset map). The inset photo shows how BRF appears today, forming a topographic rise with less than 100 feet of relief. The study area (blue circle) is located on the western part of Morven Park, which is the location of a mansion (inset photo) occupied by an early twentieth century governor of Virginia, now a historic site, museum, and equestrian park. The image is approximately 4.5 miles across.

Plate 2. photos of an outcrop of Catoctin Formation metamorphic rocks from the southern end of the study area (see Plate 1). These rocks are between 1 by and 540 my old; they were originally basalts, tuffs, sandstone, siltstone; before being buried and metamorphosed into their current lithologies. This plate shows the outcrop along strike (A) and along dip (B), revealing sedimentary structures and grain sizes that suggest this is a cross-bedded sandstone with intercalated siltstone. These sediments (and associated volcanics not seen in the study area) were deposited when proto-North America collided with proto-Europe during the late Proterozoic. They were then buried deeply enough to be altered but not so much to become gneiss, or melt to become igneous rocks. Their current orientation has a strike of 35 east of north, and a dip of approximately 30 degrees, but this deformation was not caused during the collision that formed Pangea.

Plate 3. Close-up of the outcrop in Plate 2. The top of the sequence is a bed 12 inches thick. Below this is are several cross-bedded layers (identified by the lines that dip to the left) that are discontinuous, and intercalated with thin, massive (no lamination) beds. The lowest visible beds are lenticular in this view. This kind of cross-bedding suggests that these sandy sediments were deposited in a river, where one-directional currents create uniform cross-beds. There is no evidence of gravel and the sand is fairly well sorted (as best as I could tell from the outcrop), suggesting that this was not near the source but in an alluvial fan. The heterogeneous lithologies of the Catoctin Formation are likely due to delta switching, i.e., the main channel moving across a relatively flat area before entering either a sea or lake. There are no fossils in these rocks because they predate the appearance of shell-forming invertebrates like clams, snails, etc. There were no land plants either, so their organic carbon content is practically zero.

Plate 4. Close-up from the outcrop in Plate 3, showing lenses of white minerals within laminated, slightly folded sandstone beds. Such lenticular bedding is common in metamorphic rocks because of the high heat and pressure caused by deep burial. Incompatible elements (e.g., calcium or silicon) are squeezed out of the rocks and form blebs of new minerals, such as calcite (excess calcium) or quartz (excess silicon). There were no shell-forming animals (invertebrates form their shells of calcium minerals) when these sediments were deposited, but carbonate rocks have been produced by abiotic processes as long as 4 billion years ago; not to mention algal mats created by stromatolites. Marble (metamorphosed carbonate rock) is reported as lenses within the Catoctin Formation. These lenses would have been originally deposited as either algal mats or chemical sediments.

Plate 5. Close-up from Plate 3, showing details of one of the lenses. Note the lamination in the sandstone and transition between the two mineralogies where they are in contact in middle of the photo. I didn’t use acid to test for calcite (it fizzes under dilute HCL) because the motto of Rocks and (no) Roads is to use our eyes and available information. However, note the white rectangle at the top-center of the photo; it is very similar to the shape of calcite crystals. Other such shapes are visible if you open the image, zoom in, and pan around. I am going with this being a lens of calcite, crystallized from mineralogically incompatible calcium, because that is consistent with the official description of the Catoctin Formation lithologies.

Plate 6. Photos of phyllite found loose on the ridge west of the Bull Run Fault (see Plate 1). (A) The sheen of this sample is caused by aligned muscovite minerals during burial. (B) A close-up reveals the platy texture typical of phyllite, which typically forms from shale and is intermediate in metamorphic grade between slate and schist. The chemistry of these rocks suggests that they were originally deposited as tuff (a fine-grained volcanic deposit) rather than mud. Of course, once the ash settled it would have been transported by rivers and become intercalated with the sandstone seen in Plate 2. This sample shows no sign of stream transport (e.g. rounded into a cobble), so it is probably a remnant of eroded, overlying (i.e. younger) volcanic sediments, after the quiescent period represented by the older sediments from Plate 2.

Plate 7. Photo looking north at an outcrop of the Jurassic diabase (age ~175 my) indicated in Plate 1, exposed by a stream that cuts across the Bull Run Fault. These are the youngest rocks within the region after rifting of Pangea had begun. Deeply buried rocks melt and some of the magma rises, following joints and weak lines in the overlying, solid rocks. Diabase, which has a composition similar to basalt, is formed like this although it often feeds volcanoes. The continental crust was stretched thin and fractured, allowing the diabase to work its way towards the surface. It only appears as lenses like those seen in Plate 2 in this area.

Plate 8. This image shows the typical growth for trees along the rocky crest of the hill seen in Plate 1. These large trees started out growing in fractures in the rock and, in some kind of enhanced biochemical and physical weathering, thrived and grew to be tall trees, probably almost a hundred years old. I’ve seen trees growing from large joints in rocks before, but never a forest that looks like it is set in concrete. There is absolutely no soil on these ridges but that didn’t stop Mother Nature.

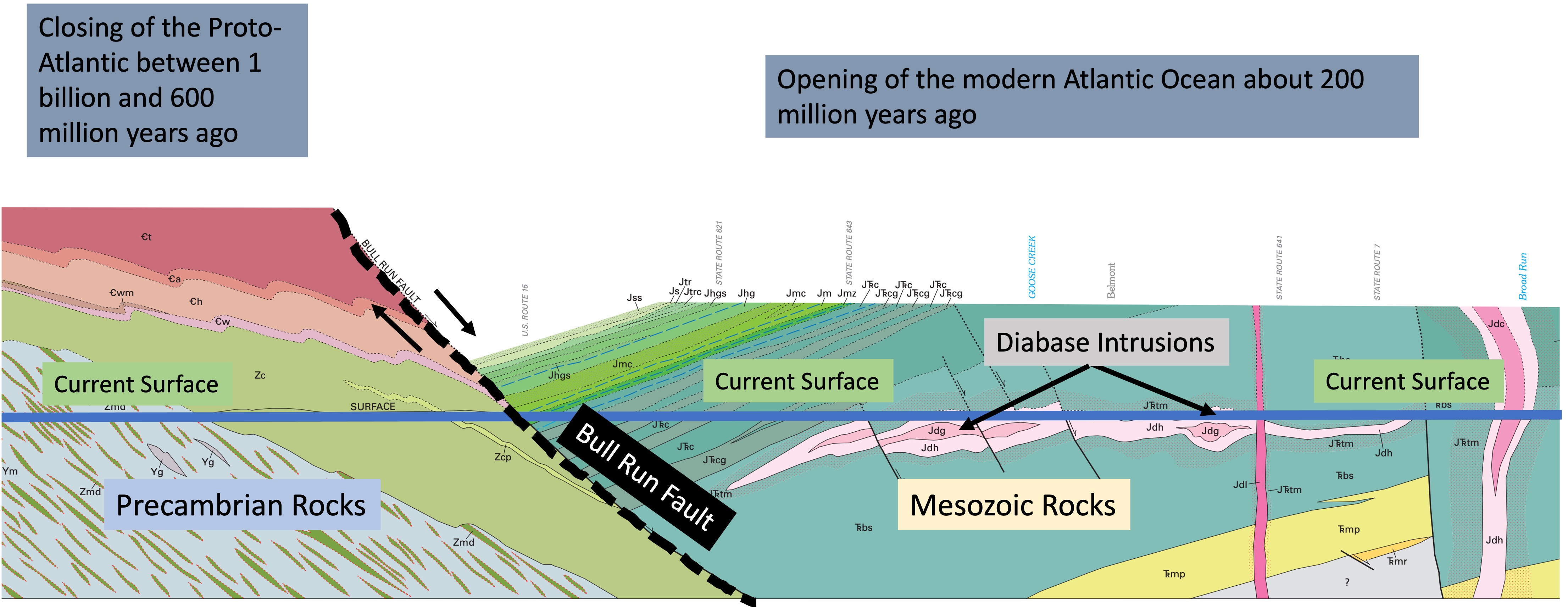

Plate 9. Cross-section across Loudon County, Virginia, from west to east. Bull Run Fault became active during the rifting of Pangea as the supercontinent stretched. The younger rocks on the east (right side of BRF) slipped down this fault surface, leaving the older rocks several thousand feet higher than where they belong stratigraphically (beneath the younger rocks). The arrows indicate the relative movement along BRF. The current erosional surface is indicated by the blue, horizontal line. This displacement has juxtaposed sedimentary and volcanic rocks that were created during the closing of an ocean basin (e.g. Plates 2-6), more than 600 my ago, with sedimentary and igneous rocks emplaced during the opening of another ocean basin, about 200 my ago (previous post ). The diabase intrusions (Plate 7) were emplaced during the latter event, cutting through rocks that weren’t much older than them (if you call 20 my a short time interval). The earth’s crust moves slowly over a semi-molten mantle, but it never stops moving back and forth; and the result is there to be seen if we’re looking for it.

Sugarland Run: Reaching Towards the Potomac

The confluence of Sugarland Run (left) and the Potomac River (right). This is where today’s trip ends. The trees haven’t recovered their foliage yet because it is late March. We’re going to start upriver about a mile and end up here.

The last post covered the area inside the blue ellipse. We encountered 200 Ma shales and sandstones of the Balls Bluff shale. we expect to see similar rocks today, but we’ll be entering the Potomac flood plain. The red ellipse is where we are in this post. The numbers will be referred to later as the locations where photos were taken. The dashed lines for “rock” and “gravel” are approximate locations where the bed of Sugarland Run changed composition. It should be interesting.

Here at Site 1, the bed consists of large, angular boulders with rounded corners. These rocks didn’t travel far, probably eroded from now-gone cliffs like we saw upstream. This location, as with similar rocky transits we saw upstream, represents a point where the stream flows over an exposed ledge of bedrock. This is very common for streams in this area.

View looking downstream (north) at Site 1. Note the dramatic change in stream bed composition. The bar on the right consists of silt and gravel. Note also the eroded, soft bank on the left. We have entered the ancestral Potomac flood plain.

At Site 2 (see map above for location) gravel bars like this were found where a smaller stream entered Sugarland Run. It is probable that the current stream is cutting through ancient sediments because there is no source for gravel like this anywhere around. These are recycled deposits.

Confluence of Sugarland Run and a side channel at Site 2. Channels like this criss-cross the ancient flood plain. These are larger than those we saw further upstream on the Potomac in a previous post.

This photo from Site 2 is the last appearance of bedrock in the stream bed. Note the flat surface across the stream that tilts slightly towards the camera. This is a bedding surface for the Balls Bluff Siltstone. Upstream, these rocks form low cliffs and are tilted away from the modern stream. It is likely that overlying beds have been eroded after tens-of-millions of years by the ancestral Potomac River. The change in dip suggests, further, that there is a structural feature between this location and a mile upstream. There is some evidence for a fault that runs along Sugarland Run several miles upstream. It was probably part of regional adjustment during uplift over the last 200 my.

As with other streams on the Potomac River flood plain, there has been rapid erosion. This example from Site 3 can be dated by the age of the tree. I don’t know how old it is, but it is certainly less than a century. What is unusual is that this erosion is occurring inside a bend. Usually streams cut on the inside of a meander and deposit point bars on the outside. We’ve seen this at every scale in previous posts. From what I’ve read there has been rapid erosion in the last few decades because of urbanization. We saw an extreme example in the last post. The field data suggests that Sugarland Run is widening but not meandering. This is not a natural process in unconsolidated sediments like these. The ancestral Sugarland Run certainly does meander (see map above), but this rapid erosion unaccompanied by channel migration is not natural.

There are several small lakes near the modern Potomac River, such as this one (just north of the Site 3 label in the map above). Sugarland Run passes it within 100 yards, through unconsolidated muddy sediments. Features like this are difficult to understand because the age relationship between the stream and lake cannot be unambiguously identified through radiometric dating. Both developed in sediments of the same age, older than either feature. These lakes (see map above) don’t look like oxbow lakes. Given the common occurrence of depressions throughout the area, which form small ponds and lakes during the wet season, the geological fact that the Potomac floodplain has wandered across a wide swath of the area (see for example a previous post), and the lack of any outflow to a modern stream (see map), it is probable that these lakes represent undulations in the ancient flood plain and Sugarland Run is younger. It just happened to miss the lake as it cut down through the soft sediments without meandering.

This meander at Site 3 shows how Sugarland Run is becoming incised rather than following a typical meandering trajectory, as at Horseshoe Bend on the Colorado River. The scale is drastically smaller but the processes are similar; the stream lacks the energy to erode the banks and becomes “trapped”, so it cuts downward as the upriver source is uplifted relative to the outflow. In addition, this small stream appears to be widening, as seen in the eroded tree on the bank in a previous photo.

Another interesting feature we saw between Sites 3 and 4 was a couple of elevated flat surfaces like this one, seen in the center-left of the photo, about halfway between the current stream bed and surface. These benches were small in area (less than 100 feet) and at the current water level of the stream. My best guess (a common occurrence in geology) is that they were point bars when Sugarland Run was smaller and are relict features on the modern Potomac flood plain.

Here we are about 100 yards from the Potomac. There is no delta associated with Sugarland Run but there is a bar at its mouth (see first photo).

Sugarland Run is an intermediate-sized stream flowing into the Potomac River. Goose Creek is one of the larger ones, which supplies drinking water for the region, whereas Horsepen Run is a small one. Despite the difference in flow between these tributaries, they display similar geomorphic features (e.g. meandering, point bars, gravel and muddy beds, recent erosion and entrenchment) because they all cross the wide, ancient Potomac floodplain composed of mixed sediment types. The modern Potomac River itself is less than four-million years old although there is evidence of the ancestral river flowing though this area back 20 my. The supply of sediment has decreased over the eons as the ancestral Appalachian Mountains eroded, so we don’t see the kind of sedimentation today that would have been occurring several million years ago.

The sediments being eroded by modern streams like Sugarland Run record a climate and topography very different from what we see today. However, the physical processes were the same and the landscape was shaped, ultimately, by geological processes occurring deep within the earth’s crust. These same constraints produced the ice age that is closing in our times and associated fluctuations in sea level, adding nuances and new themes to the unfolding story of our Earth.

Recent Comments