BHCC 2013: Full Size and Mixed Geology

This is the final post from the Black Hills Cruiser Classic in July 2013. I don’t know if the organizers planned it this way, but the final trail was mixed 4-5s over a varied terrane near the camp.

This trail started on some alluvium near a creek and climbed thru a fault zone with Paleozoic LS and pC basement rocks, but no granite on the outcrop map. We were too far north for the Harney Granite pluton to be exposed except possibly in faults…

Off we go, thru the creek, which was a sign of water everywhere but NO mud, for those who h8 mud!

and a stop in the vale to air down (most were using ~10 psi)…

I never saw the white pickup on the trail; I think there were plenty of exits on this trail…

Then we traversed some faulted and weathered LS along several gullies. One of these had a 5 feet ledge for the left wheel and a LARGE rock (house size) on the right that gave a lot of problem to limited articulation suspension systems, e.g., a vintage FJ40 ahead almost never got over one. I made it but smashed the right rear corner. It was so scary I didn’t notice at the time.

Then we climbed out of the gully (i.e. fault zone) and were in pC crystalline basement (really HARD rock). I wimped out and took the easier routes after realizing the damage I had already done.

It was hard enough that a group of photographers collected.

I wish (almost) that I had done those 4+/5 challenges. Oh well, there’s always next time! These rocks were more like Jake from the first day. I didn’t get images from the “rock pile”, which was an erosional feature at the base of a cliff in the pC metamorphics, but I saw a lot of teetering (high centered on top of a pile of rubble) by those who opted for it.

BHCC 2013: The Iceman Cometh

The next day came with no permanent damage but a set of badly damaged wheels, seriously dented muffler and tailpipe, and pieces of FJ Cruiser plastic missing. Today we were doing the Iceman trail (rating 4), which means hard but not fatal most of the time. The same group showed up so we were getting used to it. Iceman is located in the Paleozoic limestones that form the sedimentary cover of the Black Hills Pluton/Batholith complex. Here is the overview image that shows where Iceman is located.

This trail starts out in a wide( ~300 yd) entrance to a gently sloping canyon. It traverses the nearly horizontal limestone and we negotiated a series of ledges that got progressively higher downhill. The trail ends at a very narrow entrance to a fissure that our guide, Raylon, said he walked once when he broke down here. He informed us it could not be negotiated by any vehicle and was difficult even on foot.

The limestone forms ledges where water flows over it and thus the name no doubt comes from attempts to negotiate this creek/stream/glacier? when ice is still present. We had an epic failure of the IFS on Rayon’s Forerunner and left it on the trail. I had to show you this image, which shows the extremes we go to when a non-field-repairable vehicle blocks the exit (like pushing a damaged aircraft over the side of a carrier).

We had to climb those LS (limestone) ledges to get out, and it was obvious that others hadn’t thought that far ahead from all of the ramps that had been constructed to ease the exit. Note the ramp built of cobbles used on this ledge as I descend it.

Two last points about LS; it is not as hard as granite (i.e. quartz, which has a hardness of 7.5), with a hardness of only 3.5 whereas steel is ~5-6. However, it has a higher density (specific gravity ~3.2) than quartz (sg =2.65), so it bends steel better than granite, which just cuts through metal!

It sprinkled and sleeted as we drove back up Iceman, thus earning the name, and the exit was now a slippery muddy slope that required full throttle by everyone to get out. The reward was happy hour at a drive-in straight out of Happy Days or American Graffiti.

One final word; only damaged the muffler some more and learned how to drive the automatic transmission over rocks while using the sliders to wedge the FJ through narrow openings.

BHCC 2013: When Geology and Offroading Meet

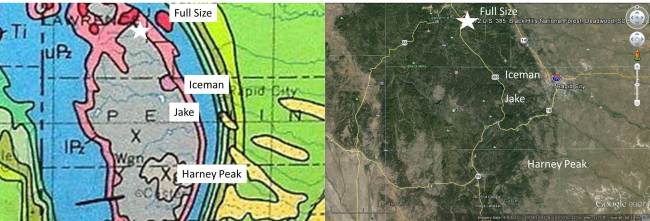

This post covers three trails that were part of the BHCC 2013: (1) Jake; (2) Iceman; and (3) Full Size. Each trail required most of a day and was located several miles from the main camp at Wild Bill’s near Deadwood. I am only going to discuss the relationship between the geology and the off-roading experience today. The maps below are approximately the same region; the projections are different so they don’t match exactly but I have labeled important locations that are shown in later photos.

The star indicates the location of the campground where the event activities and camping were located. Unlike some events, this one occurred in a national forest instead of an ORV (Off-Road Vehicle) park. Wild Bill’s is at the top of a long climb up from the mineralized zone around Lead and Deadwood. Many faults and dikes are visible in these roadcuts. This image shows 30 MA dikes (light colored) along bedding/structural weaknesses in >2 GA metasediments, which hit the angular unconformity at the Great Unconformity that separates ~1.5 GA rocks from 600 MA rocks. These Cambrian sediments are not metamorphic (no great heat or pressure) and they are nearly flat; the hot molten magma turns horizontal to follow their bedding surfaces.

Before hitting the trails, I drove south to Harney Peak and hiked to the fire tower at the top (~7300 feet). This is the backbone of the Harney Granite that was intruded ~1.6 GA. This image shows the trail and the overall shape of the pluton. The fire tower is above the word “Black” in the GoogleEarth image.

The complex relationships between the surrounding metasedimentary rock and the Harney Granite are seen in this image from the Mt. Rushmore monument.

The first trail we followed was Jake (see image above). We drove into the pC metamorphic rocks and followed a forest service trail to a narrow gully that began climbing to the east. These rocks were originally deposited as mud/sand in nearshore environments like Louisiana ~2.3 GA and were buried. At ~1.5 GA the Harney Granite was emplaced (over tens of millions of years) and they were warped during the coeval orogeny. This occurred at about 8 miles below the surface. When they were uplifted at ~30 MA, they fractured into a common hexagonal fracture pattern that leaves their edges like knives. They are also very dense because of the high pressure. They form a truly tiring trail that sliced my aluminum wheels like butter.

Black Hills Cruiser Classic 2013: Getting There

The next couple of posts are describing a trip I made in July 2013 to the Black Hills Cruiser Classic (BHCC). This first post describes the geologic and social settings in getting there, which is ~1500 miles from home.

This post is kept brief by referring to our Family web page for a trip we took in 2010 (timkeen.net), as well as the excellent Roadside Geology of South Dakota (J. P. Gries, Mountain Press Pub., Missoula, MO).

After driving across the coastal plain into Arkansas, I turned west at Hot Springs and drove along the axis of the Ouachita Mtns, which bisect AR. I began the northward trek when I intersected US 71 N and traversed the Arkansas Valley as well as the Ozark Mtns in the north. Paleozoic limestones are nearly horizontal in this area, with erosion being responsible for the steep grades seen in this image in the AR valley province (terrane).

I crossed the Missouri R. at Kansas City and stayed to the east of the Great Plains following the same route we did in 2010. This choice followed the bluffs along the western border of Iowa and stayed close to the river, which allowed me to review my history by visiting a MO stated park dedicated to the Lewis and Clark expedition. I wish I could go up the river in a boat like this reproduction; that would have been cool.

Instead, I continued north and spent the night at one of my favorite American traditions, a small motel in the middle of nowhere. I think I could have driven thru the walls, they were so flimsy–like the sign (does that say Bates Motel?).

The next day I crossed the northern Great Plains on the Pierre Shale. This is a Late Cretaceous (66-90 MA) mostly clay formation that was deposited by the inland sea that covered the entire central US at that time. It has irregular landscape because of glaciation between ~200 and 15 KA. It is just plain flat today, except for the Missouri R. valley (timkeen.net).

Stream gravel caps small buttes like these, indicating erosion of a younger surface above the current Pierre Shale topography. After Wall, SD, the land climbs because of the doming associated with the Black Hills…

It’s not my Fault

This post finds us back in Central Highlands of AZ, but we continue examining batholiths. We are going to take another day trip north of Lake Pleasant (see Day Tripping post). This time we are going to traverse a faulted region with the Tertiary volcanics and a pC granitic batholith, as seen in the geologic map of this area.

The goal of this trip is a back door to Crown King, up the Agua Fria river drainage basin. This route traverses a complex terrain composed of 1.6 GA (billion years ago) granite and metamorphic rocks, and younger volcanics and sediments. This trip is different from the previous posts because the granite (pluton/batholith) is not entire, but has been broken by a number of geologic faults. These breaks in the Earth’s crust are indicated by heavy lines on a geologic map of this area.

The pC granites (xG, colored gray on the map) are differentiated based on the distribution of elements Na (sodium), Ca (calcium), and K (potassium) within the minerals that construct them. The observed variability is astounding, probably because (1) this is a mining area and there have been many detailed geochemical studies; and (2) this is a batholith that represents many pulses of intrusion between 1.5 and 1.8 GA; that is a period of ~300 million years.

This blog isn’t about geology only, however. The ride up all of those faults from <1200 feet to 5800 feet at Crown King is not possible without road building; this brings us to an important concept in offroading. Much of the adventure lies in traversing roads that were built but not maintained. This is one example, as seen in this photo of the switchbacks required to make the climb on unmaintained access trails from Pleasant to Crown King.

The need for access and thus roads in underlined by the evidence of abandoned habitation along the way.

As with other steep climbs, this one also ends in a high-altitude wonderland of pine and deciduous trees and a lake.

To summarize this easy 4×4 day trip; we climbed through Holocene colluvium and river sediments (again) and through a highly faulted and mineralized (mining) zone thru Tertiary volcanics into a pC batholith that is the highest elevation in the region (i.e., Crown KING), where Americans have extracted vast amounts of copper, tin, lead (not much gold) at great effort.

Their efforts (and Mother Natures’) allow us to take this fun day trip today!

Rubicon and the Sierra Nevada Batholith

If an orogeny lasts a long time over a great extent of space, plutons overlap and produce batholiths like the Sierra Nevada. This batholith is seen from space as the large white area in this GoogleEarth image.

The extent of the batholith is seen in in a geologic map of California.

The small rectangle is the approximate location of the famous Rubicon Run from Morristown to L. Tahoe, California. I made this run with some fellow offroaders in 1983. The granites are shown in red, which is a lot bigger than the Harney Granite pluton. It isn’t much higher, however, with peaks at ~8700 feet. These intrusive rocks are also much younger, being intruded over millions of years during the Mesozoic period (~88-210 million).

The climb into the Sierra Nevada batholith is thru scenic forests that become primordial on the trail, with streams and many boulders. The trail is difficult to find without a guide over the solid granite mountain.

More “gates” that keep large vehicles out finally lead to a glacial valley at the top, where a couple of days are spent camping.

After a rest and any needed repairs, we head downhill to the south shore of L. Tahoe and a great meal before heading back to the Basin and Range.

Granite and Plutons

I have been avoiding dealing too much with absolute age in these early posts because geology is about looking at the earth and seeing differences in the rocks, soils, plants, and (yes) even weather. What does all of this have to do with a pluton/batholith?

Sediments are deposited in more-or-less horizontal form and thus we see younger over older. Intrusive rocks do not obey this rule (Steno’s Law) but they can appear anytime. However, unlike sediments, which are generally not directly datable using a proven scientific method, we can date various unstable radioactive isotopes in igneous rock because they melted and the minerals (mostly) participated in this operation.

I am not going to talk about radioactive dating but it allows a quantitative date to be assigned to igneous and metamorphic rocks under most circumstances. Plutons are emplaced from the lower crust and thus Steno’s Law does not apply.

When we go off road, we see a LOT of granite, which is an intrusive rock. Granite forms really nice gravel roads and it is quite popular in CO where granite allows a reduced road paving budget.

Here is a textbook example of a granite pluton, Mount Rushmore in the Black Hills of S. Dakota. The first image shows how it looks from space and the second shows colored geology over a relief map.

The granitic rock is the oval covered with trees because of its higher elevation. This is the Harney Granite (~1.6 billion). It can be seen in some close-up images that show how it melts the rock it is intruded into the surrounding sedimentary rocks at our family web page. This example is small enough to be viewed in its entirety from Harney Peak.

This beautiful pluton has had all of the overlying softer limestone eroded. It is also a great hike to the top at about 7300 feet.

Day Tripping

I am developing this reporting method using old pictures from my time as a Geology student at Arizona State University (ASU). A lot of fun and challenging off-roading could be had in a day; I often spent Saturday doing this. This post is a revisionist day trip blog post, i.e., I don’t remember much (it was 1983) but I have the kind of pictures I still take (incomplete and episodic), so this is kind of what to expect in newer reports.

Eventually, I needed a smaller and more capable vehicle than the 6500 lb truck, so I swapped it for a 1980 Jeep CJ5 and dropped 3000 lbs and several feet of length and width.

This proved a wise choice, for this report describes a trip with a new friend, who rode with me in the Jeep because his truck couldn’t get through the gate (i.e., a really narrow crevice that even squeezed the Jeep). I met a fellow off-roader (anonymous) on this day, and never saw them again. We met by accident at the gate, which we both hoped led to a new route to Bartlett Reservoir that didn’t involve a road. This Google Earth image shows the region NE of Phx.

This image has been annotated to show the overview of the geology on the recent image. We (independently) drove out of Phx on the Beeline Hwy (route 87) and left at a randomly chosen trail (elevation ~2500 feet). We followed (sort of) the solid black line and met somewhere within 1/2 mile of the road where an interesting wash (possibly Log Corral Wash) was blocked by a LARGE (house-size) block of pC metamorphic rock–no picture?

We drove up a narrow rocky wash, which suggests that we were travelling thru a very hard rock rather than the recent volcanics, as seen in the geologic map. To be sure, I should have gotten a sample, because, if memory serves, this looked like pC Mazatzal Quartzite (really hard metamorphic rock), which I later studied as a geology student. It is possible that we were in a fault zone where some of the older rocks could be expected to be exposed.

After passing thru the narrow point in the wash, we climbed up the ridge in the Quaternary lava flows (< 2.6 million yrs.) to an elevation of ~3000 feet, and came to a real gate (this is open range), which we followed downhill towards the reservoir.

We joined up with the service road for the 115 kV power line and continued downhill on this unmaintained trail. The peaks in the background of this image and the previous are remnants of the PC Mazatzal Quartzite, which forms most peaks in the area. The reservoir can be seen in the background.

The road on the opposite side of the lake is the main access seen in the satellite image above. We continued through the pC rocks, which are highly faulted in this area and followed the service “road” around the east side of Bartlett Dam, constructed in 1936-1939 (spillway elevation is 1600 feet). The image below is a poor-man’s panorama. I missed the middle of the sequence. Downstream is to the left and the dam is to the right.

It turns out that service roads are not really trails or roads; this one ended in a bare exposure of pC rock that could not be climbed without (possibly) modern rock-crawler rigs! We had to backtrack and retrieve the truck anyway. One last photo op at Bartlett Dam.

This post hopefully demonstrates why we like to go offroad. This view and great ride can’t be had any other way, except for hiking. I can’t hike (never could) because of my knees so this is my best shot, not to mention it doesn’t require a week to do. The second point is the summary of this trip. We explored the Central Highlands of AZ, which is a transition between the Basin and Range and the CO Plateau in this area. We saw the change in geomorphology and rock type as we passed from young volcanic rocks to pC metamorphic and igneous rocks. We also saw the impact of extensive normal faulting, which produced this juxtaposition of different rocks.

One final point: these volcanic rocks look like the ones from the L. Pleasant area (see previous post) but they are millions of years younger. Only radiometric dating methods could have determined this in such a variable geological terrane.

Cheers to a great day!

Putting it Together

Eventually, I could get my own vehicle. I started with a 1968 International Harvester Pickup with 4WD. It was okay but I upgraded to a new 1979 Ford F250 and started exploring the Basin and Range with more confidence.

It was very easy to go offroad back then NW of Phx. This post gives a simple example of what this blog is about.

This image shows a friend standing on a ridge within the Hieroglyphic Mtns. southwest of Lake Pleasant, which is NW of Phx. In the background is the Central Arizona Project canal, which was constructed between 1973 and 1994. This area can be seen from satellite images, which weren’t publically available in 1981

The CAP crosses this image along the south with a couple of bends near the residential area west of 303. L. Pleasant is the body of water to the north. The canal goes through tunnels where it crosses the Hieroglyphic Mts. In order to understand where the photo was taken, and what it shows, we can look at the bedrock plotted over the relief as seen below.

This geologic map is coarse and doesn’t show the necessary detail where we were. We can use the Roadside Geology book to see that the Hieroglyphic Mountains are Precambrian schist (metamorphic). They show up as small ranges within the sediment that fills the Phx Basin.

The approximate location of the photo is indicated by a black rectangle in this image. We were driving up a ridge constructed of Precambrian (pC) metamorphic (purple color to the W) rocks. The volcanic rocks (extrusive) on the map are the remnants of a faulted and eroded lava plateau from Mid-Tertiary (~30 Million) mountain building (orogeny) The pC rocks are schists (modified mud stone)that were uplifted from deep in the crust, not necessarily when the volcanics were produced. This image shows one of the many small ridges within the Hieroglyphic Mtns, and a dry river bed that drains the Central Highland terrane west of L. Pleasant.

To summarize this easy day trip, we drove north along some recent colluvium (Holocene river/slope deposits) and climbed into a ridge of pC metamorphic rocks overlooking a depression (L. Pleasant) that probably formed along a fault (break in the Earth’s crust) during the Basin and Range event. To the west we had a nice view of one of the many ranges that were uplifted many miles to be seen by offroaders like us today.

The crux of this post is that >1 billion years ago, there was an ocean/coastline here and sediments were deposited in an environment we can only estimate. These were buried deep to be heated and crushed to form metamorphic rocks (schists). They waited…and then were uplifted. Eventually, volcanics were produced (like Hawaii today) and flowed out over them. Erosion from water wore all of these down to produce the Agua Fria river drainage system and finally, we (people) built a dam and dug a canal across it all.

Awesome!

When Geography and Geology Meet

These early posts will be interspersed with any new activities but I am going to follow the introductory theme today by merging geology with geomorphology or physical geography. I mentioned travelling around AZ in our cars on roads, which can be quite an experience in the western US. The concept of a terrane is convenient to merge the rocks and geography. A picture is really worth a thousand words when it comes to geography, as seen in this USGS relief map of AZ.

These maps use shading to give the impression of elevation. For example, the entire NE part of AZ is the Colorado Plateau at 5000-7000 feet above sea level. Phoenix is at an elevation of ~1100′. These are excellent examples of terranes; The Colorado Plateau and the Basin and Range–PHX is in a basin but it is surrounded by small ranges, like Phx Mtns, South Mtn, White Tank Mtns, etc).

The soils within these basins are sandy with clean sand in the river beds (note how many there are in the Phx area, as indicated by blue lines). They can be very fertile because the sediment was carried from the distant mountains (and chemical/physical weathering are strong in rivers); such soils, like those in Maricopa County, i.e., modern Phx, are an ideal combination of sand and clay.

These terranes are also seen in the geologic map of AZ.

This map shows relief with shading as well as the rock types. It shows that the CO Plateau is fairly uniform sedimentary rocks whereas the Basin and Range terrane includes small patches of darker colored metamorphic (purple) and igneous (red/brown) rocks associated with local high relief in the small mountain ranges. These are surrounded by sediment that eroded from these mountains. I am not going to get into these specific rocks types on this page because excellent layman descriptions can be found in Roadside Geology of Arizona by Halka Chronic (Mtn. Press Publishing, Missoula, Montana), and

Recent Comments