Cool Pleistocene Basalts

The title of this post, besides being a bad pun, refers to the fascinating secondary fabric we found in some basalt flows not far from our house in Melbourne. An hour-long car ride took us to Organ Pipes National Park, near the Melbourne International Airport. The sign at the park entrance gives an overview of the park (Fig. 1). We’re going to see some of this for ourselves.

The now-familiar Victoria geologic map (Fig. 2) reveals that the park is located well within the Pleistocene volcanic field, with radiometric ages of approximately 700 ka to 1 ma. Note also the thin slice of Paleozoic sedimentary rocks in the area (indicated by the purple color). We’ll see those as well today.

The terrain consists of a plateau dissected by streams like Jacksons Creek running through Organ Pipes National Park (OPNP). The flat surface was created by the lava flows that emanated from numerous volcanic cones. The landscape seen in Fig. 3 hasn’t changed that much since these flows covered the land, filling creeks and leveling the terrain.

The asphalt path seen in Fig. 3 leads down a steep slope to Jacksons Creek, ~150 feet below the pediment level. We’ll take a look at the basalt from the top of the plateau later. This week, we’re going to start from the oldest rocks and work our way upward. So let’s get going.

Jacksons Creek, about twenty feet wide and probably no more than a few feet deep, winds its way along the canyon. On the other bank, where we couldn’t get, we discovered Silurian sandstones (according to the park info about 420 million years old), with an apparent dip of more than 60 degrees to the NE (Fig. 4 is looking towards the SE).

This is as close as we could get. These sedimentary rocks were tilted (folded and faulted) during collision with suspect terranes and finally Gondwana throughout the Paleozoic, ending in the early Mesozoic period (about 200 MY ago). The red color of these sediments suggest that they were nonmarine, probably deposited in a river floodplain, which is consistent with the nearshore marine depositional environment we saw in Ordovician rocks we encountered in a previous post. Those were of late Ordovician age, only a few million years before these nonmarine sediments were deposited. The land was rising (relative to sea level) about 400 MY ago, but not suddenly.

The Ordovician marine rocks from the last post were also tilted and even overturned. They showed evidence of compression shifting from SE early to SW during a later episode of deformation. We can’t be certain of the direction of compression of these Silurian rocks, but it appears to have been (in OPNP anyway) directed along a NE line, i.e., about 90 from the viewing direction of Fig. 4. Before we leave this fragment of the distant past, let’s see what else we can get out of these rocks. Figure 5 shows a very simple analysis of the compression directions I have estimated from these rocks and the Ordovician sediments from last week.

This analysis comes with (at least) two warnings: 1) deformation has nothing to do with the age of the rocks except that it couldn’t have occurred for millions of years after deposition of the youngest deformed rocks (Silurian); and 2) I have put an arrowhead on the stress line for Phase I based on what I know of the Tasman Orogeny. Phase I occurred first and was mild, based on low-angle anticlines seen at Yarra Bend Park. Phase II was later and stress was towards the NE (present coordinates) because of the steep dip angle of an anticline axis at Yarra Bend. This is for certain. The Silurian rocks at OPNP may reflect Phase I deformation, but we couldn’t see them, or any evidence, from across Jacksons Creek. However, they are consistent with strong compression towards the NE.

No younger sedimentary rocks are found in the area, so it is assumed that whatever rocks were deposited or erupted (volcanic) in this area between Silurian and Pleistocene were eroded away. So, we’ll skip over the Mesozoic and focus on this post’s titular rocks.

Figure 6 shows an unconformity between the tilted Silurian rocks and younger volcanic rocks that overlay them. This could probably be called an angular unconformity because lava is deposited in layers, just like sediments.

The viewing angle is different from Fig. 4, but the general bedding of the Silurian sedimentary rocks is indicated by yellow hand-drawn lines. The black line is the approximate contact between the older rocks and the Pleistocene volcanics. That was the approximate land surface ~one million years ago. Pretty cool (another bad pun). The white square indicates Fig. 7.

The viewing angle has changed again, but the bump of the black line in Fig. 6 is the point in Fig. 7. The angular fragments of basalt in Fig. 7 indicate the thin soil that has developed over a million years in this semi-arid climate. It isn’t very often that a contact like this can be seen, a hiatus of more than 300 million years unobscured by soil and vegetation. Alas, it was hidden from us by logistics and our unwillingness to find a way to get over/around the creek, in violation of the law, to get a closer look. Before we move on, I want to share an interesting photograph of this exposure (Fig. 8). It demonstrates how dangerous it is to use color in assessing a rock from a distance. The white exposure is the same as the yellow rock but something was different when it was buried and became cemented…diagenesis is a complex process.

Moving upstream, and higher into Pleistocene basalt, we see some interesting features of this particular lava flow in this particular location. This is tricky because we don’t know how thick the flow is; nevertheless, let’s go to the feature that gives the park its name to begin.

This is classic columnar jointing. It is thought to occur during uniform cooling of igneous rock. A famous example is Devil’s Tower, Wyoming. The rocks of OPNP are definitely extrusive, unlike other examples. We have seen the contact between this basalt and the surface it flowed over. If experts cannot agree on how an igneous rock that never saw the light of day formed this unique structure, they certainly aren’t going to agree on these basalts, especially the more spectacular fabric seen throughout the park.

This is a back-of-the-envelope estimation of the orientation of the columns visible at the main exposure along Jacksons Creek. I’m not going to talk about the mechanics of the analysis because there are some notes on the figure. The white ellipses, representing the ends of columns, tell a story too unbelievable to accept if the pictures weren’t telling the story. Within a few hundred yards (at most) from their contact with the land surface this basalt flowed over, they were cooling so uniformly that these elongate fractures formed. More unbelievable, the cooling joints are twisted. It gets more bizarre.

Figure 1 indicates a site called “Rosette Rock.” We went to take a look. Figure 11 shows what we found.

For scale, this is an exposure of basalt approximately 50 feet in height, along Jacksons Creek. The yellow lines represent the directions of the cooling joints. I didn’t use ellipses because there was very little variation out of the plane orthogonal to an axis pointing at the observer. In other words, this is a wheel, with the joints radiating from a central point, a hub if you like. I have no more explanation of this now than I did when I first saw it in person. I don’t think anyone does. This makes Devil’s Tower look like a stick figure. We followed the creek to see these curious structures up close.

About 500 yards upstream, around a meander (See Fig. 1), we came upon the “Tesselated Pavement” (Fig. 12), a “bedding plane” of the basalt probably created by the pounding of basalt boulders and pebbles over the millennia (Fig. 13).

This exposure seemed to be part of a resistant tongue protruding from the thick flows supporting the hill in the background of Fig. 13. There were several other such resistant tongues along a couple of hundred yards of Jacksons Creek’s quiet surface. The exposure in Fig. 13 was continuous with the massive outcrop seen in Fig. 14.

This rock wasn’t as columnar and it was fractured badly. It was threatening to collapse on the trail. The length of Jacksons Creek was a surreal geological experience. For example, the rocks shown in Fig. 14 were crumbling, yet there is no scree collected at the base of the low cliff. Very strange, especially in a protected national park. The smooth surface in Fig. 13 was less than 100 feet from Fig. 14 and at the same elevation, at creek level. Very strange. It’s as if someone built a scene for a movie but didn’t understand geological processes. Very strange, especially in a semiarid environment.

I looked for evidence of paleosol within the basalt, but all I found were irregular areas of remineralization (Fig. 15).

This was either a single flow, or a series that occurred before weathering had proceeded enough to leave evidence. However, the erosional terrace seen in Fig. 9 suggests that there were multiple flows. We retraced our steps back to the top of the basalt flow at OPNP and noted changes in the rock that support rapid deposition of all of the basalts observed in the area.

Figure 16 reminds us of the columnar jointing deeper within the flow. Note the top of the photo shows the present surface.

Here are some photos of exposed basalt from near the top of the sequence (Fig. 17). Note brittle fractures (left photo), and thin bedding reminiscent of the blocks seen in Fig. 14, but weathered.

A close-up view of the rocks seen in Fig. 17 reveals vesicles and a hint of depositional flattening, as if the lava were dense enough to condense (Fig. 18).

At the top of the plateau, the basalt contains more vesicles and shows no sign of compression under its own weight (Fig. 19).

To summarize this trip, which covered more than 400 million years, most of it unrecorded, what is today Organ Pipes National Park was a river plain that was buried before being deformed by the pressure of tectonic plates colliding to form Gondwana. This took several hundred million years. Whatever rocks were pushed up to form mountains were long gone, leaving an erosional surface not unlike that today, which was covered by lava flows that filled every gully, creek, and canyon in the area. Erosion had to begin again to erode Jacksons Creek anew. It seems to me that OPNP is filled with a single flow that ended with gaseous magma capping a fine-grained volcanic rock that cooled and later fractured by mechanisms that are not well understood.

The rocks tell us it is so.

Deformed Ordovician Nearshore Marine Rocks in Melbourne

We didn’t have to travel very far to observe an interesting geologic exposure, on the outskirts of Melbourne. We went to Yarra Bend Park, situated along the banks of the Yarra River, where a small stone dam creates some rapidly flowing water.

Our location in Fig. 1 is at the confluence of the Yarra River and Merri Creek, the smaller stream on the left (western) side of the map, where the highway first enters the park area (colored in the map). The Yarra is a meandering river here and reverses direction, thus the name of the area (Yarra Bend). There is an exposure of interbedded sandstone and mudstone along the southern bank of the river, at the entrance to the park, near an observation deck. Figure 2, taken from the northern bank shows the exposure nicely.

A plaque mounted on the observation deck summarizes the geologic history of the area (Fig. 3).

The dark and light layers in Fig. 3 schematically represent the tilted sandstone/mudstone sequence seen across the river in Fig. 4. However, there’s more going on than that. Let’s look at the geologic map to get an idea (Fig. 5).

This report describes rocks ESE of Melbourne, where the orange (volcanic) rocks are in contact with the purple sedimentary rocks in Fig. 5. Yarra Bend park is located where the volcanic rock field forms a point that touches the main road (below the “o” in Melbourne). A previous post identified some older basalts along the coast to the SW, but those were about 30 MY old. These are much younger. They came from a volcanic field to the west, as suggested by the massive field of volcanic rocks west of Melbourne (see Fig. 5). In other words, Yarra Bend is at the eastern edge of a volcanic flow. There were no exposures of these basalts in Yarra Bend, however, because the rocks had eroded to form slopes and a black soil. Figure 6 shows some loose boulders used to reinforce the bank of Merri Creek under a highway overpass.

They ranged from a few feet across to the size of a small car.

Figure 7 is a close-up of a boulder. Note the holes (vesicles), suggesting this was a gaseous basalt. Large phenocrysts are not visible. The rusty surface suggests that the lava contained significant iron-bearing minerals (probably amphiboles or pyroxenes). There is no evidence of older sedimentary rocks on the north side of the river. In fact, elevations are much lower on the north side. Thus, the north and south banks of the Yarra River have completely different geology. According to the sign (Fig. 3), the basalts redirected the river against the bluffs to the south, implying that the different geomorphology existed at that time.

We drove to the south bank of the river and parked the car at the top of a ridge (seen in the background of Fig. 2), on a paved road less than a hundred feet above the river. We walked along the paved road that led down to the river, following a footpath (dash-dot line in Fig. 1) to the river at the extreme left of Fig. 1. Ridges of resistant rock formed the northward pointing headlands that defined the river’s meanders.

The ridge where we parked was directly underlain by thin-bedded sandstone/mudstone beds tilted in a generally SE direction (no strikes or dips were measured). However, small-amplitude folds were visible (Fig. 8, looking to the north).

The SE dip angle varied from about 45 degrees to vertical. The variation of bed orientation by so much over distances of less than twenty feet suggests that the sediments were very ductile during deformation. This inference is supported by remineralization, as seen in Fig. 9. Note that this thin bed was protruding from the layers shown in Fig. 8.

There was also evidence of brittle deformation, including hexagonal fracturing (not shown), which probably occurred during uplift and a reduction in temperature and pressure.

Without reviewing the geological literature on SE Australia, especially the Tasman fold belt, we can use our field data to construct a preliminary structural history of Yarra Bend Park. First, sand and mud were deposited about 420 MY ago, during the Ordovician period, along a coastline not that different than that existing today in the area.

Over an unknown time interval (certainly millions of years), the layers of sand and mud were buried 6 to 50 km beneath the surface (detailed mineralogy would limit this depth range substantially) and cemented to become rock. The entire region was then compressed along an approximately N-S axis and the lithified rocks seen here were folded. Only small folds are visible in this area (wavelengths less than 10 m and amplitudes less than 1 m), but they certainly would have been associated with larger scale folds during regional compression. The sediments were heated and compressed enough during this interval (lasting possibly millions of years) for the original sediment grains to remineralize as seen in Fig. 9.

The anticline seen in Fig. 8 was tilted more than 45 degrees in a generally easterly direction. A key observation for these rocks is that they were overturned after being folded; i.e., the fold itself was compressed along its axis and became nearly vertical. Rocks buried many kilometers beneath the surface rotated more than 90 degrees (overturned) indicates compression, usually associated with extreme folding. However, this small exposure reveals two compression directions, oriented at right angles, from N-S and E-W (rough estimates), which suggests a rotational stress regime. The rocks only recorded two members of what was probably continuous (but variable) compression while the tectonic plate carrying Yarra Bend Park rotated, dragged along by upper mantle convection.

Imagine slapping two balls of play dough together and rolling them (slowly) in your palms, in a circular motion. That is what happened to these sediments/rocks. But we don’t know when, not from our observations. Such a complex squeezing explains the fabric of these rocks. They were first pushed (like a rug that folds up) from one direction, then another.

There is another problem, however. Did the second compression regime occur when the rocks were ductile (folding) or when they were brittle (faulting)? Answering this question would tell us a lot about the timing of the compression; e.g., whether it continued while these rocks were being unburied by erosion of overlaying rocks; or if the stress changed direction while the rocks were still deeply buried. Since our observations don’t include microfabric analysis, and no faults are evident, we have to use indirect methods to address the problem.

The top of the low hill seen in Fig. 4 reveals thin layers of sandstone (Fig. 10).

The apparent dip on these beds is consistently 30-40 degrees and there is no evidence of folds (compare Fig. 10 to Fig. 8). There is also no sign of the variability in dip angle that was seen further up the hill, much less overturned beds. Folding is not uniform throughout a thickness of sedimentary rock. Invariably, different kinds of sediment/rock compress at different rates, depending on lithology, water content, etc. Thus, there is always some slippage along low-angle delimitation planes (usually bedding surfaces) whenever a thickness of rock is compressed. The difference in deformation style cannot therefore be used as evidence of brittle deformation during the second phase of compression, although it is consistent with the substantial difference in dip angle, especially overturned beds.

Indirect support for inferring brittle deformation also comes from the difference in geology and geomorphology across the Yarra River. The absence of Paleozoic rocks on the north side, taken in concert with the lower elevations there, suggests the presence of a fault underneath the river. This could be a normal fault, with the northern side of the river dropping to form a graben. However, the lengthy compressional stress suggested by the deformation of the sediments is more consistent with a reverse fault, with the south bank being the hanging wall. There is no basalt on the south side, and only a few cobbles along the river bank.

Figure 11 shows a thick bed of massive sandstone exposed 100 feet further along the trail, maybe 20 feet down-section. Closer examination of the photograph reveals low-angle cross-bedding, i.e., generated by waves with very little transport of sand.

We can do a back-of-the-envelope calculation (aka guesstimate) to get an idea of the time between the massive nearshore sand and the later deposition of alternating sand and mud. I’m going to use SI units because they’re easier for estimating. If my field estimate of 7 m (about 20 feet) is okay (not likely), then we can easily estimate the time in years between the thick sandy layer in Fig. 11 and the interbedded sand/mud layers in Fig. 10. Using a conservative sedimentation rate for a deltaic environment (like the central Gulf of Mexico) of 0.002 m/year (2 mm/year), we can confidently calculate a reasonable age difference. Dividing 7 m of total sediment by a sedimentation rate of 0.002 m/year means that only 3500 years were required to go from the depositional environment represented by Fig. 11 to that seen in Fig. 10.

The sediments immediately below the massive bed (Fig. 12) are like those above.

That thick (more than 6 feet) layer of sand was deposited in a sandy nearshore environment, as indicated by thin bedding (visible by zooming in on the photo) and no mud at all. Figure 12 suggests that we should be wary of projecting a single stratigraphic section (one-dimensional) into three-dimensions, i.e., it is very likely that a massive bed as seen in Fig. 12 was deposited someplace else at any time during the time span represented by these rocks. The low-angle crossbedding suggests that this may have been a shoal or bar deposited on a mixed clastic coastline. It’s time to go further down section, into the past.

We followed a trail (including some cement steps cast into a flood-control levee) to river level. This short hike took us another 60 feet down section, which means we travelled ten-thousand years further back in time from Fig. 12. Here’s what we found.

This is a section that could be taken straight out of the northern Gulf of Mexico, in another ten-million years. Sand and mud are equally available. That only happens when there is active erosion in an upland with a variety of rocks available, and plenty of accommodation space for the sediment; i.e., relative sea level is rising, whether due to sea level increasing or subsidence. Yarra Bend Park was located in an active delta. Let’s look at those sediment layers closely.

Figure 14 is a close-up of the strata in Fig. 13, which reveals irregular bedding typical of nearshore marine sediments. Finer grained sedimentary particles have weathered out to reveal low-angle, planar cross-beds. There was plenty of mud available. I want to emphasize that this exposure is less than an acre in horizontal extent, so this entire thickness of maybe 50 m represents on the order of 25 thousand years of deposition and erosion of sand and mud on an acre of seafloor. In other words, the sedimentary environments represented by Figs. 11 and 12 were certainly found within a few kilometers of each other at ANY given time.

The massive (almost 6 feet) thick bed in Fig. 11 can be examined at river-bank level because of the dip of the sedimentary rock layers (see Fig. 4). We went down-section and then turned to go back up section, but at a different angle, which is why I’m estimating distances and ages. These could all be much more accurate with some geometry. Figure 15 shows a 3-foot thick cross-bedded section at approximately a right angle to Fig. 11. This allows us to examine two different potential flow directions at the same time, albeit separated by maybe fifty feet.

Note how the dark/light lineations (laminae) are tilted slightly towards the left, the angle decreasing from the bottom of the “bed” to the top. Figure 15 suggests weak bedload transport with a leftward component. This transport weakened upwards. This is consistent with sand being transported along the bed by weak currents that varied irregularly, preventing consistent cross-bedding sets to develop. The more planar nature of lamination in Fig. 11 supports this conclusion because the flow would have been approximately “into” the rock surface in Fig. 11. This is an environment typically encountered below fair-weather wave base (e.g. deeper than 30 feet). The sediment size is uniform, suggesting continuous deposition rather than episodic. Storm and flood beds tend to have a lag deposit at the bottom and fine upward.

Using a “standard” deltaic sedimentation rate of 2 mm/year, we can [switch back to SI mode and] estimate that this meter-thick sand layer was deposited during five thousand years of continuous input from a land source. However, average sedimentation rates are meaningless for a sand body like Fig. 15 because sand will be concentrated by waves and currents into shoals at any given time. Furthermore, our estimate assumes a steady rate of subsidence; space had to be made between the ocean surface and bottom for this sand to accumulate.

Figure 16 reveals a sand layer with similar crossbedding to the overlaying bed but a different color and appearance; it is more rounded and less massive. This is probably an artifact of diagenesis that tells us nothing about its depositional environment.

A little further down-section (Fig. 17) shows crossbedding similar to Fig. 14, but with less mud.

I have described the sedimentary rocks of Yarra Bend Park in the order they were encountered in the field. Rather than rewrite this post, I’m going to summarize the geological history and refer to the photos in chronological sequence. I won’t make this mistake again.

Around 420 million years ago, the study area was receiving predominantly muddy sediment, with sand being deposited in thin beds (Figs. 13 and 14). Sand increased for several thousand years as the muddy layers decreased in thickness (Fig. 17), until an interval of major sand deposition occurs over a very short time span (Fig. 12), producing several massive, cross bedded layers (Figs. 4, 11, 15, and 16). These were probably shoals or barrier islands, possibly due to the river mouth migrating to the local area (delta switching). Subequal sand/mud deposition resumed in discrete beds (Figs. 8 and 10) for tens of thousands of years. If these rocks are 150 m in thickness, Yarra Bend Park was part of a stable clastic shelf for 75 thousand years.

Deposition continued and the sediments were buried to at least 6 km, where they were cemented to become sandstone and shale. This almost certainly took several million years. Compression, probably caused by collision with Gondwana, more than likely occurred during deposition of these sediments in a foreland basin. They were first folded from current south while still deeply buried but the direction of collision rotated ninety degrees clockwise as the rocks were unburied. With lower pressure and temperature, the deformation changed from ductile to brittle and faults would have occurred along planes of weakness, leading to a fault that defines the Yarra River’s modern channel.

Volcanism was continuous for the last 30 million years, culminating with the basalt flow that reached Yarra Bend Park about 700,000 years ago, pushing the river against this promontory of hard, Ordovician sedimentary rocks. They resisted erosion as the basalt weathered away from their flank, leaving us to ponder the amazing history of this unknown park on the fringe of civilization, buried in one of the most complex orogenic belts in the world.

Coastal Geology of Victoria, Australia

This blog has been quiet for a while, not because I wasn’t traversing lands with a rich geological history; instead, my primary audience (off-road enthusiasts) had expressed no interest in geology. It turns out that they were typical Americans. Also, I’ve been busy writing novels and doing other literary actions, but now I’m writing this for myself. This is a record of my travels, with enough details to remind me of where I went and why it’s worth remembering.

This post reports on my first excursion since coming to Australia, a trip from Melbourne to Apollo Bay along the coastline of Bass Strait. Let’s get some perspective.

This is the SE tip of Australia. Melbourne is labeled, as is Tasmania and Bass Strait, which is 150 miles (~350 km) across. This post covers the very short distance from Melbourne to the tip of the continent to the SW. This was a day trip of only 200 km, which took about four hours because we stopped a lot.

Time for some geology. This trip is entirely located within the state of Victoria. The geologic map I’ll be using is from 1982 but I don’t think it’s very out of date because the geology of Australia has not been explored in detail. Here’s a portion of the Victoria geologic map, with city names. It is a rectangle bounded by Melbourne on the NE and the NW corner of Bass Strait on the SW.

We drove our trusty Toyota Yaris along Highway A1 and turned south, reaching the coast at Torquay, due south of the western tip of Port Phillip Bay. This is a geologically interesting area at the southern edge of a Quaternary volcanic zone (orange background with v’s scattered in the geologic map), overlain on Tertiary (25-65 MYA) marine sediments (tan area in center of above figure).

The underlying sediments of Tertiary age formed ridges along the shoreline covered by sand from the eroding poorly cemented sandstones, as seen in these photos from Spring Creek Park in Torquay.

Note the yellowish, non-marine coloration of the sediments in the right photo. They erode rapidly and don’t form bluffs. The absolute (radiometric) age of these sediments was unknown at the time of this writing, but this exposure is the top of the stratigraphic column in this area; in other words, we will be going further back in time as we head westward.

Many faults have been inferred for the region, as shown in a hypothesized cross-section along the coast.

Note the field geologists’ interpretation of faults, shown by nearly vertical lines, in the middle of the section. The green colors represent sections of the earth’s upper crust dominated by non-marine sediments whereas the red are volcanics from about 29 MYA. The slivers of orange in the center are the sediments shown in the previous photos. They are riding on older Cretaceous (green) sediments with volcanics systematically exposed and subsequently eroded, because of uplift along faults (vertical lines).

Our trip westward along the coast took us into the older, Cretaceous, sediments (shown in green in the previous maps) beginning southwest of Anglesea, where the Great Ocean Road entered a National nature preserve that resembles Southern California near San Diego. This photo was taken near the edge of a bluff overlooking the coast, but it was closed because of recent cliff collapse.

There are a number of rivers flowing to the coast from the inland uplands, but few of them reach their destination by late spring. The underlying rocky ridges form barriers that the river channels are forced to follow parallel to the coast for kilometers, forming structural lagoons with seasonal mixing with the ocean. The Anglesea River is a good example. The channel formed a lagoon that did not debouch into the ocean, although at high tide, during storms, there was inflow from the ocean. Here’s a look at this phenomenon.

The first photo shows an anatomizing river, with side channels and bars, as if reaching its destination. The second shows the berm that prevents the river’s flow from reaching the ocean. The berm is overtopped only during storms from sea, or high-water flows from land. All of the river’s flow is absorbed into the dry sand in this arid environment. The river flow is not sediment laden, as shown in this photo of birds bathing in the shallow water.

We tasted the water, and it was slightly brackish, from seawater overtopping the berm. The rivers don’t carry a lot of sediment from the arid, low-relief landscape through which they run. Thus, the substantial wave energy impacting this coastline is not spent redistributing sediment from rivers and instead erodes the coastline. The next two images show how this process occurs.

The first photo looks west from the Anglesea River, where the rocks are weaker and form a less-steep bluff. They also reveal changes in dip, from almost horizontal to dipping seaward at more than 30 degrees to the right of the photo, near the river’s mouth. This may well have been a fault zone during a regional uplift event. The photo on the right is from east of the river, where the bluffs are much stronger. However, rubble piles at the base of the cliff indicate where collapse has occurred. This is the area where the previous image was taken from the top of the cliff.

Note the dark coloration of the lower half of the bluff face in the second photo above. This region experienced extensive volcanism about 30 million years ago, when Australia is hypothesized to have passed over an upper mantle “hot spot.” There is an extensive volcanic field north of this area and basalt blocks have been brought in to reduce coastal erosion; however, the dark layer in the photo is a layer of ash that has formed a weak volcanic rock called tuff. Here’s an example of this tuff in place over older sandy sediments.

It is much less resistant to erosion by wave action than the blocks brought in for erosion control (seen in the left foreground of the previous photo). As the cliff retreats, the lower rock forms a table covered by a thin veneer of sand reworked continuously by waves. Slightly more resistant rock forms ledges that are exposed at low tide, as seen in this photo.

These exposed outcrops are visible along this entire section of coast, which is underlain by these same sandstone/conglomerate rocks. For example, here’s a photo taken at Aireys Inlet a few miles to the southwest. Note the tuff layer at the base of the pillar, seen clearly in the close-up photo below.

Because of the variable wave approach (from SW to SE), and heterogeneities in rock strength as well as structural factors such as faulting, many small pocket beaches have formed, many of which are the mouths of seasonal rivers and streams. Here is a good example.

Some of these bays are very large, as is this example from near Aireys Inlet.

The coast is lined with steep mountains eroded within Cretaceous, non nonmarine sedimentary rocks, forming very short streams that are prone to flash floods during heavy rain. The streams are so steep, that waterfalls can be found within a kilometer of the coast, such as Sheoak Fall, near Lorne, shown below.

The second image shows flood debris in the foreground, more than fifty feet above the stream bed seen in the distance, deposited during a flash flood. Another feature of these coastal sediments are the presence of calcareous concretions, formed during burial and diagenesis, which dissolve out when exposed to slightly acid rainwater. They leave large voids like this.

There are even caves higher up the slopes. The entire drive to Apollo Bay was similar to what I’ve described above, sandy beaches overlaying rock shelves, with seasonal rivers debouching into the ocean. We finished the drive by following a two-lane road through Otway National Park and seeing a spectacular primordial forest that stood out in sharp contrast against the semiarid coastal environment.

Colorado’s Turbulent Past: Epilogue

We descended from our last camp site in the San Juan Mts and discovered another environmental consequence of the weathering of the volcanic and intrusive rocks from this area. As the plagioclase feldspar weathers it forms the mud we see everywhere that is low, but it also forms a thin soil on the underlying rock that is weathering in place to form regolith. The trees cannot put roots very far into this broken and weathering rock so they have very shallow roots, which allow them to be blown over by a strong wind or just fall over when they get too large. We encountered a fallen tree as we headed for Dove Creek and the highway; we think it was an aspen but none of us were experts.

We didn’t have a saw (not too well prepared) but a couple of motorcyclists riding the TAT had a small hand axe and we had a hand saw, which together were used to cut about half-way through the trunk. The winch on the lead vehicle was then used to finish breaking the fallen tree and drag it out of the road.

Our path took us through some Paleozoic rocks that survived on the flanks of the uplift associated with both Laramide and Tertiary magmatism. These older sediments had been eroded from the top of the San Juan Mts before the Tertiary volcanism but they are very thick to the south and west in New Mexico and Utah. I am not going to discuss these areas in this series of posts because we didn’t really travel through it at a leisurely rate but just headed to Monticello, UT where we ended our trip.

Here is our afterward group shot in front of the Abajo Mountains as we were preparing to head east to Louisiana, New York, and New Hampshire.

Here is our afterward group shot in front of the Abajo Mountains as we were preparing to head east to Louisiana, New York, and New Hampshire.

I like to end these trip posts with a summary. This journey covered a long period of time, from the Proterozoic (~1.7 billion year ago) granites of the Wet Mts to the Miocene (~6 million years ago) basalts of the Raton Mesa in SE Colorado. It is typical of CO’s complex geologic history that these oldest and youngest rocks are near each other where our trip began on I-25.

These two regions not only represent the entire time interval we covered in this trip, but also the end members of the igneous rocks that are produced within the earth’s crust; the Proterozoic granites were formed deep beneath the surface from magma that originated from melting of continental crust during an ancient orogeny whereas the Miocene basalts flowed out onto the land from fissures. This basalt also represents a significant contribution of their source magma from ocean crust, which has led many geologists to propose that part of the Pacific Ocean’s crust was overridden by N. America and melted beneath the continental interior to produce basalt, which is typical of ocean crust only.

Between these two extremes of igneous rock, we find granitic rocks with intermediate composition from the Laramide orogeny (~60 million years ago), which began the slow process of raising the Rocky Mts to their present elevation, and both volcanic and plutonic igneous rocks that were produced as this event wound down between approximately 36 and 20 million years ago. Many of these igneous episodes produced gold and silver deposits that occur along deep fractures in the earth’s crust, originating from mountain building ~1.7 billion years ago.

My final comment on this trip refers back to the name of this blog; the most exciting and geologically interesting parts of this journey were only possible because of roads built over the last 150 years to extract gold and silver from these mountains. The few areas where we were able to travel over designated trails that weren’t much more than tracks were limited to meadows and mesas in the SW part of the state. For this journey, we might refer to the blog as “Rocks and Roads”.

Colorado’s Turbulent Past: Tertiary Intrusive Rocks

We camped along a creek in Silverton across from a silver mine and mill, as shown in this satellite image; the mill is indicated by a white triangle. The mine and mill are now open for tours but I didn’t have the opportunity to visit them.

Here is a photo of the mill. The mine went into the mountain behind the mill, which appears to be a fault. Veins of silver and gold are frequently found along faults, which are weak lines in the crust where the high-pressure fluids can penetrate. Silverton was settled in 1874 and had a peak population of 5000 in the early 1900s. The mill is nestled against the ridge south of town.

Gold and silver milling technology was changing rapidly while Silverton was active but this mill probably first used an “arrastra” method with a horse (or maybe water power) to drag a heavy stone around a central post to crush the ore brought from the adjacent mine shaft. Water and chemicals like mercury would have been mixed with the crushed ore to form an amalgam (silver/gold plus mercury), which was heated to boil off the mercury. It is likely that this inefficient method was replaced with a Comstock mill, which used a heavy piston to crush the ore and a cyanide process would have been used to extract gold more efficiently.

After leaving Silverton, we headed west toward Ophir Pass (see photo above) where the landscape changed dramatically. This photo shows the view looking west from Ophir Pass; note the lack of vegetation in this rocky terrain. It would be extremely difficult for trees or shrubs to take root, or for lichen to grow on these constantly shifting fragments of the original volcanic rocks. It is noteworthy, however, that grass is growing at this same elevation in the background where the rocks are not as fragmented.

Note also the muddy matrix supporting the trail, which implies that these rocks contain minerals that weather rapidly to form clay, i.e., these rocks comprise much more Ca-bearing feldspars like plagioclase rather than the K-feldspars we saw early in our journey, which form gravel. This next photo shows that these rocks are very resistant to erosion where they are less fractured.

As an aside, this kind of scree is impossible to climb in a wheeled vehicle, and off-roaders avoid it like the plaque. There is no cohesion amongst these fragments and our tires just churn it up like water from a paddle wheel; of course, with enough horsepower and large enough tires it can be climbed but not consistently.

A close-up view of one of the larger fragments shows that this rock can be classified as an andesite porphyry.

The lighter colored cobble is a piece of host rock and not a mineral crystal. Zooming in shows many smaller particles of rock (not mineral) and an irregular surface texture that suggests a squeezing of the ash as it was deposited from the air and compressed as it cooled.

We continued traveling eastward until we encountered some sedimentary rocks containing sandstones and layers of coal. I have no photos of these formation however, but according to the USGS geologic map these are Cretaceous (85-60 mya) Mancos Shale, a nearshore marine deposit with coal beds, which probably contributed to the naming of Black Mesa. We chose a camp site among the Tertiary intrusive rocks as indicated by location 6 in this image.

Our campsite, among spruce and aspens, was apparently used by hunters and boy scouts. Here is a photo that includes a generic hand sample of an andesite and a 15x photo of a sample from our campsite.

The rocks (there were no exposures where we stayed) looked like this andesite porphyry from geology.com. The larger photo shows that the hand sample color of grey is probably caused by the areas of grey glassy material, which are not likely to be quartz as in the granites we saw earlier because quartz is not present in intermediate igneous rocks like this. The best general reference to understand the rocks where we stayed is the Roadside Geology of Colorado, suggests that intermediate intrusive magmas penetrated into the thick sequence of volcanic rocks to form diorite with unusually small grains because of rapid cooling so near the surface.

The rocks (there were no exposures where we stayed) looked like this andesite porphyry from geology.com. The larger photo shows that the hand sample color of grey is probably caused by the areas of grey glassy material, which are not likely to be quartz as in the granites we saw earlier because quartz is not present in intermediate igneous rocks like this. The best general reference to understand the rocks where we stayed is the Roadside Geology of Colorado, suggests that intermediate intrusive magmas penetrated into the thick sequence of volcanic rocks to form diorite with unusually small grains because of rapid cooling so near the surface.

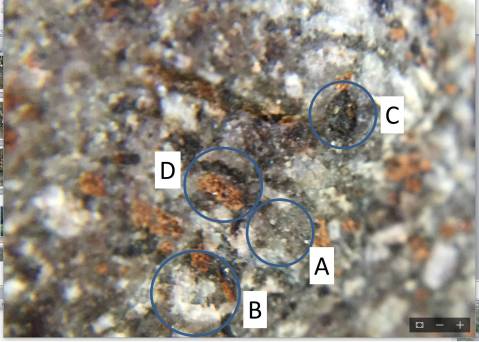

Here is another 15x photo of this rock from our campsite. This is a 15x magnification of a rock fragment at location 6.

If this hand sample had been light colored, the area indicated by circle A would be reasonably interpreted as quartz, as we saw in the sample from the Wet Mountains and the Sangre de Cristobal Mountains. However, the overall grey color of the sample, and the evidence of crystal terminations in A suggests to me, as a field geologist, that these are actually plagioclase feldspar with more Ca than Na (i.e. the more Ca the darker the plagioclase). Circle B is focusing on the white crystals that, though small, are clearly crystalline and not glass. These minerals are interlaced with the darker crystals and thus I interpret them to be a more Na-rich plagioclase feldspar (Na and Ca plagioclase form a continuous spectrum in this mineral). Area C shows a crystal of a dark mineral with much smaller crystals embedded or adjacent to it. I cannot tell if this is pyroxene or amphibole (a pyroxene-like mineral with water included in its crystal structure) but both contain Ca as well as Mg (magnesium). The most ambiguous (to me) mineral is indicated by circle D, which highlights an orange crystal; we saw pinkish to orange K-feldspar in the Proterozoic granites from the Wet Mountains but there should be no potassium in an andesite. However, some combinations of Na and Ca in the plagioclase series are this color and it is reasonable to assume (lacking thin-section analysis) that this is another phase of these common minerals.

If we estimate the composition of this sample as we did for the granites discussed in a previous post, we get the following: Ca-plagioclase = 50%; Na-plagioclase = 35%; mixed-plagioclase = 10%; amphibole = 5%. The fact that we can see crystal structures even in the smallest minerals in this sample suggests that this is one of the rapidly cooled diorites from the area rather than an andesite (volcanic), which would not have visible crystals at less than 100x magnification (e.g. under a microscope). The grey areas, in other words, are not glass by very small crystals formed near the surface.

We see the end result of this in the following photo of a local muddy area, where it was almost impossible from sliding sideways into the ruts.

As mentioned in previous posts, minerals containing Ca weather rapidly and produce by-products like clays that form MUD; however, as we saw later in our travels, when these clays form a veneer over subjacent regolith, they can be negotiated with care.

Colorado’s Turbulent Past: The Road Follows the Gold

After passing thru the narrow canyon along Mill Creek (see previous post), we spent the night at Deer Lakes in Grand Mesa-Uncompahgre-Gunnison Natl Forest before ascending the lofty passes of the San Juan Mts. It stopped raining long enough to set up camp and then continued intermittently throughout the night and next day.

We continued deeper into the middle phase (30-26 mya) volcanic rocks and the outcrops became darker colored, reflecting the chemical evolution of the magma source for these ash layers and flows. This general area is indicated as site 5 on this photo.

We continued following wide gravel roads and paved highways until we reached Lake San Cristobal (elevation 9000 feet), where the resistant welded tuffs and flows produced by this volcanic phase formed peaks such as this one overlooking the lake.

The road followed money to Lake San Cristobal, where condos are everywhere and there is even a marina with small sailboats and row boats. The pavement and new gold (money) stopped at the inlet to the lake, where Upper Lake Fork Rd became a single lane gravel trail with intermittent wide spots to let opposing traffic by.

There was a lot of traffic heading back to the lake because the trail eventually encounters andesite flows that form ledges that a bulldozer could not level. Cars were not going to Cinnamon Pass, which is where we ended up.

Here is a photo that suggests why there is a road to Cinnamon Pass and beyond. I snapped this image while trying to avoid going over the side, but it shows a vein of what is probably pyrite (fool’s gold) in the cliff overlooking the Gunnison River.

Cinnamon Pass was the second highest elevation we reached during our trip (12640 feet). The peaks, which weren’t much higher, were composed of the alternating layers of ash and lava flows. These photos show the appearance of these rocks; note the small angular shards that litter the slopes. These result from dense joint patterns that indicate extreme brittle deformation, probably from faulting that followed volcanism continually.

The headwaters of the Gunnison River ended in a shallow, flat meadow that appears to be another cirque (glacier origin area) from the recent ice ages. After crossing Cinnamon Pass, where the horizontal rain and fog/clouds made for miserable conditions, we dropped down into Animas Forks, which must have been a bustling mining community at one time. Today, however, it is represented by a few old mines (some for sale) and a USFS toilet.

This is where the road from Lake San Cristobal led. Apparently, these mines produced enough gold and silver to justify the road we followed to California Pass (elevation 12930 feet). There was snow on the ridges and their concave shapes suggests that glacial erosion was a significant factor here.

Note the sharp edges along the ridge, and the tilting of the bedding planes (original horizontal surface upon which the ash flows and lava were deposited); faulting was ubiquitous over the several million years during which middle phase volcanism took place. This was followed by the late phase volcanism associated with the Rio Grande Rift, which was discussed in the Prologue.

This image shows the irregular surface of the San Juan Mts but it cannot prepare you for the 3000 foot descent that lies ahead on the trail to Silverton.

I saw several veins of what looked like K-feldspar as we began our descent, such as this one that had not been explored by miners.

Further on, I noticed this area that had been dug in an exploratory manner but apparently it did not look promising.

This vein is more promising from an economic geology standpoint because it appears to contain much more quartz, which is associated with the last stage of magmatic fractionation that produces fluids high in elements that don’t fit well into most silicate minerals (e.g. gold, silver, rare earths).

It would appear, however, that none of these veins west of Animas Forks contained economic concentrations of gold and silver. We made our final descent to Silverton via the potentially deadly Corkscrew Gulch trail in the rain, which is why I have no photos of the trail or the rocks. As we approached US-550, the hills were dominated by light-colored talus that did not originate from mines, but from weathering of the volcanic rocks. This could be another example of dense fracture patterns associated with faulting after the original ash flows were deposited.

Colorado’s Turbulent Past: Tertiary Volcanics

We camped at Marshall Pass (location 3 in the photo below) among what we thought were Aspens, which apparently like the rocky soil that probably originated from weathering of the shales we saw in the previous post. The rocks were angular and uniformly about 8 inches in length; their size and shape are consistent with the origin of Poncha Creek following a fault through Marshall Pass. I will discuss this later.

After descending from Marshall Pass, we followed some the TAT until we entered the San Juan volcanic field. Our route took us into the early phase of this volcanic period in CO’s history about 35 mya, when volcanoes in this area were producing large amounts of ash and a lava similar in composition to the granites we have seen in previous posts. This photo shows the sudden appearance of such a volcano as we entered the San Juan Mts.

Note the rounded ridges and small peaks around the base of the main cone. The ridges are weathered lava flows, which often originate from the bottom of volcanoes and the small peaks are evidence of minor eruptions around the base of the main volcano. The flows are more visible in this photo that shows several such flows. We had the opportunity to follow a trail along one such flow, which still formed a scarp that is ~5-15 feet high after 30 my of erosion.

This photo shows one of the many well-preserved cones from the early phase of volcanism.

These volcanoes were producing mostly ash and debris that formed immobile layers that did not flow; however, they also produced ahs flows like Mt. St. Helens that would have moved rapidly down the slopes and destroyed anything in their path. These photos were taken at the approximate location indicated as “4” in the base map below.

I have some photos of these rocks that show some of the textures of these volcanic layers. This photo shows a tuff that does not appear to have melted together after the material was deposited from the air. If the fragments are hot enough and are buried under later volcanic material, they can become fused to form a “welded tuff” but that is not the case for this sample.

It has the coloration of the orthoclase (K-Feldspar) we saw in the granitic rocks from previous posts but it also has many holes (vesicles), which originally contained gas that later escaped; some of these holes are left from weathered minerals and rock fragments that were entrained during eruption. I suggest using your browser to zoom in on this image to see the remarkable number of different particles it contains, many of which are probably from the sedimentary rock through which it passed during extrusion. Here is another sample that has a different weathering color but is essentially the same.

The bulk of these tuffs is silica glass that didn’t have time to cool and form quartz crystals; it is about the same as the glass we produce for windows. I think I should again suggest that anyone looking at this post should click on these photos and zoom in with the browser to appreciate their composition.

The next photo shows a sample with easily identified quartz (the gray areas) and areas that show one of the weathering products, as shown by the white coloration. My first guess about the white material is a salt or carbonate formed from rapid decomposition of the glass to release common rock elements like Ca or Na, which formed minerals like NaCl (salt) or carbonates like calcite (CaCO3); possibly with metals included, e.g., Fe or Mg. Only laboratory analyses can identify these weathering products as well as the particles included in the original tuff.

This photo shows what an exposure of these tuffs looks like. Note the cliff at the top and the substantial debris at its base because of erosion of these relatively weak ash flows.

As we travelled to the SW, however, we entered a region where volcanism occurred several million years later, the middle phase of volcanism in the San Juan Mts. These volcanic rocks include layers of more resistant lava and welded tuffs. Here is a photo of a canyon formed from mixed layers of tuff, welded tuff, and lava flows.

The nearest outcrop also shows what could be termed a volcanic breccia because it contains large (~12 inch) cobbles in a fine-grained matrix. This photo also shows the variability of the different flows in the cliff. Note the irregularity of the layers as if they were being deposited on an eroded terrain.

As a volcano releases pressure and material from a magma chamber, a number of different types of effusives are produced; for example, we have just seen examples of tuffs that are formed from exploding liquid magma and any material it picks up as it exits the magma chamber thru channels in the rock. Here is an example of a tuff that appears to have been so hot that this liquid rock melted together to form a welded tuff.

Again, I urge the reader to zoom in on this photo, which shows fewer and smaller vesicles, as well as a layering and white minerals that I cannot identify from the photo.

The previous hand sample shows obvious layering but no evidence of flow; i.e., this material was deposited from the air and formed separate layers, possibly over a short period of time (e.g. days to weeks). I think this because there is some evidence of mixing between layers, which would not occur if it flowed or solidified between layers. This relationship is better seen in the following photo, which shows a kind of settling of an upper layer into a subjacent one.

There is no geologic reason to expect to find useful minerals (valuable) in these volcanic layers because they do not show any evidence of veins or remineralization like we saw on the previous post. Nevertheless, as we passed thru the flows of the middle phase, we crossed “Mineral Creek”, which was an opaque green as it flowed from the adjacent mountains. I stopped and took a panoramic photo of the valley and zoomed in on the opposing hills to discover an interesting symmetry across the valley.

The panorama photo has white outcrops circled. The lower photos show close-ups of the opposing sides of the valley; similar exposures occur on both sides of the valley. These volcanic layers are horizontal and there is no obvious faulting (e.g. dipping layers). There were no trails to either exposure so any mining reconnaissance did not suggest economic remineralization (i.e. gold or silver) worth road building. Until I can find the time to collect samples from both exposures and compare them, this remains a geological mystery to me.

I have a footnote to this post. We drove the dirt roads in this area under both wet and dry conditions. The roads were all wide and smooth with very little washboard texture but they created a lot of dust when dry. Weathering of the tuffs produces silt-sized glass particles that drain moisture fast but stay in the air when disturbed by truck tires, especially offroad tires. It was quite different than the gravel roads we encountered in the Wet Mountains and at Marshall Pass, both of which were based on weathered granitic rocks that produce sand grains as they erode.

Colorado’s Turbulent Past: Laramide Granitoid Plutons

We camped the first night in the Pike-San Isabel National Forest at the northern end of the Sangra de Cristo Mtns., after passing some large greenhouses filled with shrubs, either tomatoes or marijuana but probably the latter (legally grown in CO). The neighbors were all friendly as they drove by our camp site shown at location 2 in this map.

We set up in a borrow quarry for road repair soil, which was surrounded by granitic rocks similar to those seen in the Wet Mountains, but looks can be deceiving. Here is a photo of the exposure at our camp site.

I attached the 10x lens to my iPhone and took the following photo, which we will now examine.

The K-feldspar (orthoclase) is the orange mineral; it comprises about (estimating from the photo) 30% of this sample. The Na-Feldspar (albite) is the white mineral, which is about 20% of the sample, and quartz (mostly gray and pinkish in this sample) is about 40% of the sample. I would estimate that amphibole (the dark mineral; however, some of this may be other minerals that could only be identified by thin section analysis with a microscope) is about 10% of the sample. I cheated to make them add up to 100% but the errors won’t matter when we compare it to the sample from the Wet Mts shown in the last post; that sample was approximately albite = 7%; orthoclase = 50%; quartz = 40%; and amphibole = 2%. Even taking account of my errors in estimating their composition, these rocks are very different; they are also very different in age. The Wet Mts sample is ~1.5 by old whereas the Sangre de Cristo Mts rock is less than 70 my old. We will discuss this in a later post. This young age comes from the USGS CO geologic map with data sources, which lists the rocks at site 2 as Laramide Granitoid.

We crossed through the intermontane valley and the town of Salida before following Poncha Creek to Marshall Pass, indicated by location 3 in the previous photo. This was a steep rise to an elevation of 10842 feet, with a great deal of blasting, cutting and filling of deep ravines in the surrounding peaks. This leg was interesting because it took us to the Continental Divide, which separates eastward-flowing rivers from those that flow westward. It also is not within a single mountain range but instead separates the Sawatch Mts to the north from lower hills to the south.

This area also includes some of the host/country rock that the granitic rocks were intruded into. This photo shows an exposure of the host rock for the granitic intrusions at the southern end of the Sawatch Range.

This photo shows the orientation of the original bedding plane (horizontal surface of the sediments that became the rock before it was metamorphosed and intruded) of the silts and clays that were originally deposited during the Tertiary period (~65 – 2.5 mya). The tilting occurred during the Laramide Orogeny that created the Rocky Mts. The circle shows where the following photos were taken.

This first photo is at normal magnification; it shows striations on the bedding plane (indicated by black lines) that are probably from sliding during movement, overlaid on original bedding plane irregularities.

I have to admit, however, that there is always some uncertainty when only examining one exposure; many geologists have examined this region and I am implicitly including their conclusions in my discussion. When we examine the next photos, which are at 10x magnification, we can rely on our own judgement.

When we are examining igneous rocks that were crystallized from a relatively uniform temperature and composition, we can assume a lot, as I have been doing up until now. This photo shows some of the intruded rock within a few feet of the tilted rocks shown in the previous photo. I have circled regions of this small image (~1 cm in diameter) that would be of great interest to an economic geologist. I can only state with some confidence that this sample has a lot of orthoclase (reddish colored) and several different minerals that formed within small cavities when the intrusion occurred. Only microscopic study could positively identify the white mineral (albite?), the elongate crystals (orthoclase) and the very small dark minerals (pyrite?). I use question marks because these aren’t even guesses.

I took a closer look at one of these thick veins near the host rock with the 15x magnification lens to see if it would help.

The quartz is easy to identify from its gray hue (in these samples) but the circled area could be pyrite, which is also known as “fool’s gold”…where there is smoke, there’s fire…

This photo at 15x magnification shows a bleb (tiny inclusion…this one < 1 cm in diameter) of light-colored minerals in the host rock, which appears orange in this photo, despite looking gray to the naked eye (see the outcrop photo above). The minerals in the bleb look like "salt and pepper", which has no specific meaning but it suggests that the host rock produced these inclusions when heated as the Tertiary granitic melt (liquid rock before crystallizing) invaded. The gray quartz is easily identified (no longer rosy looking due to heat and pressure) and the white could be albite? but the dark minerals would require microscopic examination to identify.

I have to admit that I am writing this post several days after reaching Marshall Pass, where we discovered that I didn’t coin that phrase. Someone felt it worth digging a mine to further investigate remineralization along the fault and intrusion zone following Poncha Creek, and they put their money where their mouth was to build this great road we used.

I have one last point to make about our ride to the Continental Divide; the flat meadow at the top suggested to me that this was a cirque, where a mountain glacier formed before pushing along the fault line that now delineates Poncha Creek. These photos show why I think this.

I don’t think it was as thick as those that formed in Yellowstone and at Beartooth Pass, at the north end of Yellowstone Natl park.

Colorado’s Turbulent Past: The Proterozoic Wet Mountains

This post begins our trip on CO 69 after we left I-25 about 60 miles south of Colorado Springs. We joined the TAT as we entered the Wet Mountains, a granitic batholith that was intruded about 1.5 billion years ago when this part of N. America was colliding with island arcs (e.g., Japan and Asia today). We left the pavement on a gravel road that is typical of granitic terrains because the quartz and Na feldspar (i.e. albite) forms grains that resist chemical weathering. Here is a photo of our journey’s start.

The second photo is the Spanish Peaks, which are Tertiary (66-2.6 mya) intrusions that look like the old granites but are obviously much younger. As we approach our starting point, we drove over some remnants of the Cretaceous and older sediments I mentioned in the previous post. These younger rocks were originally deposited on the eroded surface as the Proterozoic intrusions (i.e. granite) were exposed over hundreds of millions of years. Now these sedimentary rocks have been in-turn eroded to expose (again) the granites. Geologic history is pretty complex in CO! It became obvious that we were climbing on top of a batholith as we reached >9000 feet within a few miles of our starting point.

This is a photo from a pass near the top of the batholith. This photo shows what the outcrops (aka exposures) of this granite look like.

I took some photos without magnification to show the mineral composition of the intrusion. Here is a photo of a hand sample to identify the minerals.

This rock has a mixture of both Na (sodium) and K (potassium) feldspars and quartz, as indicated. It also contains a dark mineral that is not platy and thus is either pyroxene or amphibole (i.e. like pyroxene but with water in the crystal structure). I don’t see any muscovite (a light-colored platy mineral); this assemblage indicates that it crystallized from a melt (the source liquid of the rock) that came from continental crust originally, but the lack of obvious muscovite suggests to me that it was not a highly fractionated (reprocessed) crustal source. I infer this because muscovite is found in rocks containing rare elements like lithium, beryllium, and tantalum, that require multiple rock forming stages to form minerals (they are mined for these elements).

We descended from the top of the batholith to McKenzie Junction (indicated on the map from the Prologue), where we found the host rock (aka country rock) that this granite intruded into ~1.5 billion years ago (bya). The overlying rock has been identified as a metamorphosed volcanic from chemical analysis, but in the field I really couldn’t say if it was basaltic in origin or a shale (both contain similar dark fine-grained minerals). I found really good exposures that showed how the margins of the liquid granite squeezed into the host rock. Here are a couple.

This is a great photo because it shows the banding of light and dark minerals in the metavolcanic host rock separately from the veins of the intrusion. The banding in the host rock occurs because lighter colored minerals like quartz are formed from elements that are squeezed out of the original homogeneous rock under very high temperature and pressure when mountains are formed. Miners look for these veins when searching for gold, silver, and other valuable minerals but they ignore the metamorphic banding, which has been folded during metamorphosis.

This photo shows some of the host metavolcanic rock (from ~1.5 bya) that was not under enough heat and pressure, etc. to form separate layers like the previous photo. Instead, the veins from the granite intrusion are the only banding visible. This photo was taken only less than one mile from the previous, indicating that the conditions (pressure, temperature, chemistry) within the host rock were highly variable when the veins were created.

There are a couple of other points I would like to mention. First, the creek where the last two photos were taken was generally following the NW-SE trend that has been identified as a fundamental weakness in the deep crust of CO, and thus any more recent movement has followed this trend. This is true of the famous mines like Leadville as well; even the Laramide (Tertiary) mountain building that produced the modern Rocky Mts. follows this trend. The second point is that the greater abundance of minerals containing Calcium (Ca) weather from water action easily and the trails along this creek were muddier than those on the eastern side of the Wet Mountains. Calcium doesn’t fit into very many crystal structures well, except for clays, and we know what clay makes…MUD.

One last point as an aside is that we left the Wet Mountains and arrived at Westcliffe CO, looking on the Sangro de Cristo Range to the west. These are also Proterozoic rocks of metamorphic origin, volcanic and sedimentary. We didn’t go there but here is a photo of them; just on the other side of this range is the Great Sand Dunes Natl. Park.

The last photo I have for this post is of some of the Paleozoic sediments that have survived north of Westcliffe. These were exposed in large cliffs as we travelled northward to go around the Sangre de Cristo Mtns.

Colorado and its turbulent past: Prologue

This prologue introduces a series of posts that will hopefully capture the look and feel of Colorado (hereinafter CO) from the perspective of an off road enthusiast. I am joining some fellow off roaders to traverse CO from east to west along the Trans America Trail (TAT) as modified for four-wheel-drive vehicles. We are picking up the TAT from MacKenzie CO rather from the SE corner of the state because of time constraints but I hope this post will introduce the parts we miss on our trek. Here is a track of our path across the Rockies overlain on a Google Earth image.

Our starting point at MacKenzie CO is indicated by the white square. I did drive along I25 (US87 on the image)east of the Sangre de Cristo Mtns and I will integrate this as best I can in this Prologue. We won’t be missing too much, however, because we will be going through the San Juan Mtns., which are also a major part of the geologic history of CO.

My primary source for the geology of CO is the excellent book by Halka Chronic and Felice Williams, Roadside Geology of Colorado. I will also use general sources that are appropriate. I am relying on geologic maps from the USGS. I will also use the Colorado Geologic Survey’s available data where I can, including maps.

This voyage didn’t start as far east as previous posts because I have moved to Baton Rouge, only about a mile from the Mississippi River. The first part of the journey in time and space is a retread of a previous trip, as I discussed in a previous post. It begins by crossing the Mississippi River and encountering multiple shorelines as sea level has changed in the last 2.5 my. This journey takes us though the Eocene (56-34 my) sediments of NE Texas as we approach Dallas on I20. As I travelled west along I20, the marine sedimentary rocks; which varied between sands, mud, and limestone (deep water); become older, finally reaching early Cretaceous (~120 my) in Fort Worth.

After heading NW before daylight, I crossed over the angular unconformity between the early Cretaceous sediments and mostly Permian (300-250 mya)sedimentary rocks along US 287 between Dallas and Amarillo (shown by the white line in the map below).

Note how the contour of the Cretaceous (140-65 mya) sediments near Dallas (brown color) cuts across the contours of the Permian sediments to the NW, which are shades of blue. This gap between Permian and Cretaceous sediments represents erosion of this area during an interval that includes the Ouachita Orogeny (~318-271 mya) of the Arkansas, Texas, and Oklahoma, the Marathon Uplift of West Texas, and probably the Llano Uplift of Central Texas. The Permian sediments include most lithologies, from sand and shale to evaporates and carbonates. This area was undergoing rapid changes in the shallow water environments during this time, ultimately leading to uplift and erosion.

As I travelled NW from Amarillo, I saw some Tertiary sediments that formed a cap rock, which formed small ledges where recent erosion had cut into this surface. Tertiary basalt flows started capping older sediments near the NM border as I entered a volcanic field that is contemporary with the Rio Grande Rift over the last 70 my.

My route took me across the NE corner of NM and through this volcanic field. There were several cinder cones and many basalt flows capping Paleozoic sedimentary rocks in this area.

This cinder cone was one of several spaced several kilometers apart. These were isolated whereas a much larger volcano only a km or so away had flows originating from near its base.

The basalt creates resistant surfaces and mesas form. The underlying rock is Mesozoic sandstones. These mesas only covered several miles along I25 as I headed north so this is not a giant field but probably an outlier from the much more extensive volcanics to the SW in NM and west in CO.

The subjacent Cretaceous sandstones are thin to massive bedded with cross bedding visible from the highway in road cuts. It also contains coal seams, which were common from this geologic period. These are still mined and train loads were headed south.

I drove north up I25 on top of the Cretaceous Pierre Shale, which forms most of the Great Plains. This mostly mud rock was deposited by the Western Interior Seaway that covered the middle of N. America. Thick sections of the slightly older Niobrara Limestone were visible east of the interstate whereas the Cretaceous sandstone was dominant until Colorado Springs, with granite plutonic rocks forming the back bone of the Spanish Peaks and the Front Range in the north, but that is another post.

Recent Comments