Quaternary Geology on Mt. Rainier

Figure 1. View of Mt Rainier from the west. At 14410 feet, it is the most prominent peak in the contiguous United States. It has 28 glaciers, with the largest total surface area in the lower states–35 square miles. Mt Rainier is a stratovolcano, composed of andesitic lava (rather than basalt), material ejected from the summit, and ash layers. This type of volcano is commonly found in subduction zones; they tend to have explosive eruptions (e.g. Mt Saint Helens). The oldest rocks on Mt Rainier are about 500,000 years old. It is active and listed as a decadal volcano–one of the most dangerous volcanoes in the world. Its last major eruption, accompanied by caldera collapse, was 5000 years ago, but minor activity was noted during the nineteenth century.

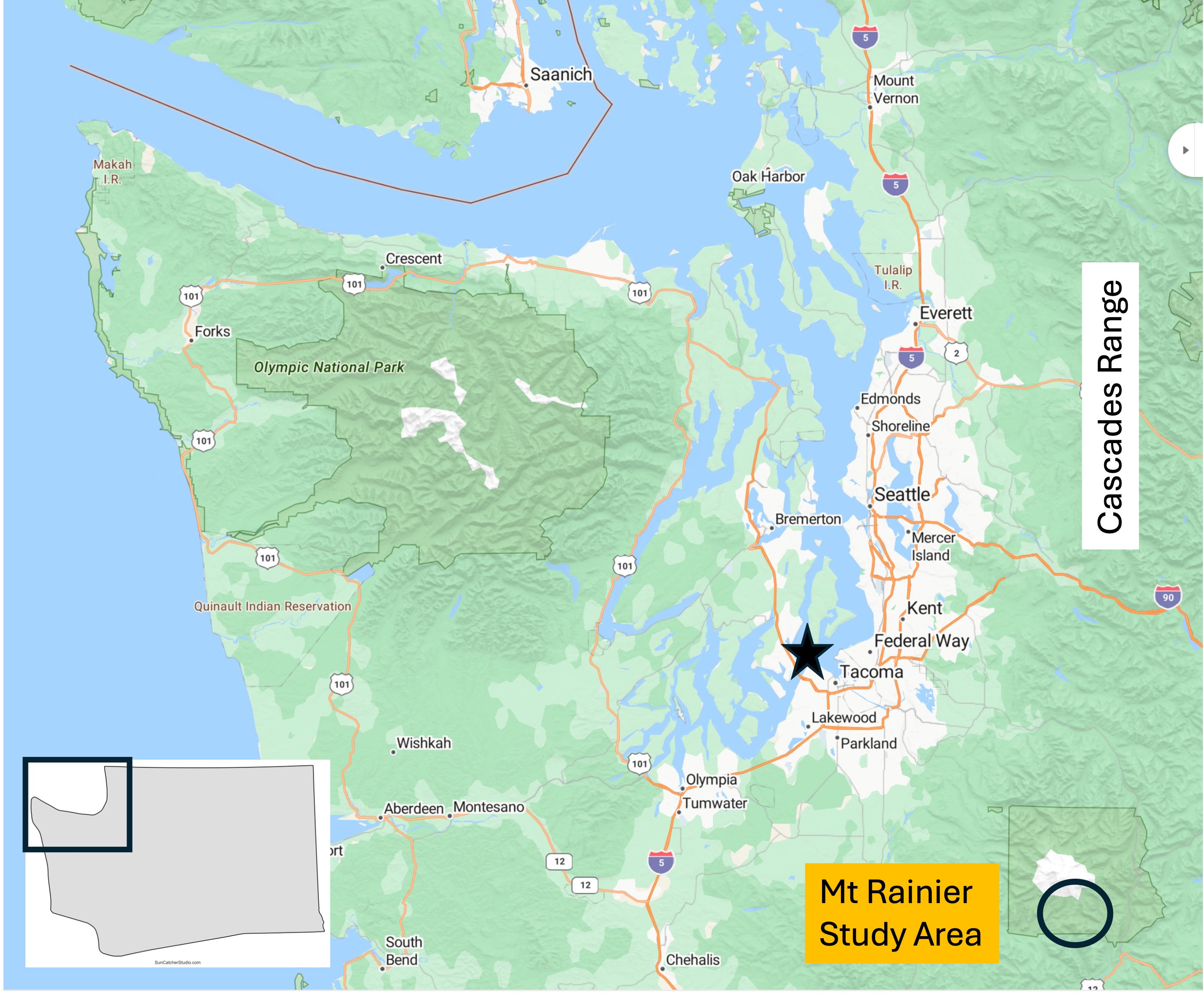

Figure 2. From my home in Tacoma (star) it’s a two-hour drive to Mt Rainier National Park. It is part of the Cascades Range, which comprises many well-known volcanoes like Mt Baker, Mt St. Helens, and Mt Hood.

Figure 3. This photo was taken on the south flank at an elevation of about 5400 feet, near the visitor’s center. It was a beautiful day and there were a lot of people preparing for some cross-country skiing on a couple of feet of snow. From this elevation it takes 2-3 days to reach the summit, almost 9000 feet higher. It’s hard to imagine it being so high and taking so long to reach.

Figure 4. These southern volcanic mountains are part of the Tatoosh Range, with peaks of about 6600 feet. Most of the volcanic rocks comprising these mountains are andesite, intermediate in composition between basalt and rhyolite. It is also very viscous, behaving like peanut butter and thus not flowing well. Andesite is commonly found at convergent plate boundaries where it is thought to result from mixing of basalt (from the oceanic crust), continental crust, and sediments accumulated in the accretionary prism.

Figure 5. Map of the 28 glaciers on Mt. Rainier. The glaciers fill canyons and valleys that were partly cut by ice. Figure 3 shows a smooth mountain, but in reality most of the smooth areas are the surfaces of glaciers. We’ll look at one below. The ellipse indicates the area discussed in this post.

Figure 6. (A) Narada Falls interrupts the descent of Paradise River, fed by Paradise Glacier (see Fig. 5 for location), making it drop a couple hundred feet over a thick layer of andesite. Andesite tends to form blocky flows, as shown in the right side of the photo, where the water seems to be climbing down steps. (B) Possible contact between younger volcanic and older intrusive rocks. Igneous activity within the area has been continuous for at least 50 my, during which time erosion has exposed older intrusive rocks like this granodiorite, which is part of a pluton intruded between 23 and 5 Ma. It is important to keep in mind that the volcanic rocks originated in plutons (magma chambers) emplaced miles beneath the surface. As they are exposed, new volcanoes form as more magma is injected into the shallow crust in a continuous process. (C) Differential weathering has accentuated layering in this volcanic rock, which was probably created by a series of ash layers deposited in quick succession–geologically speaking.

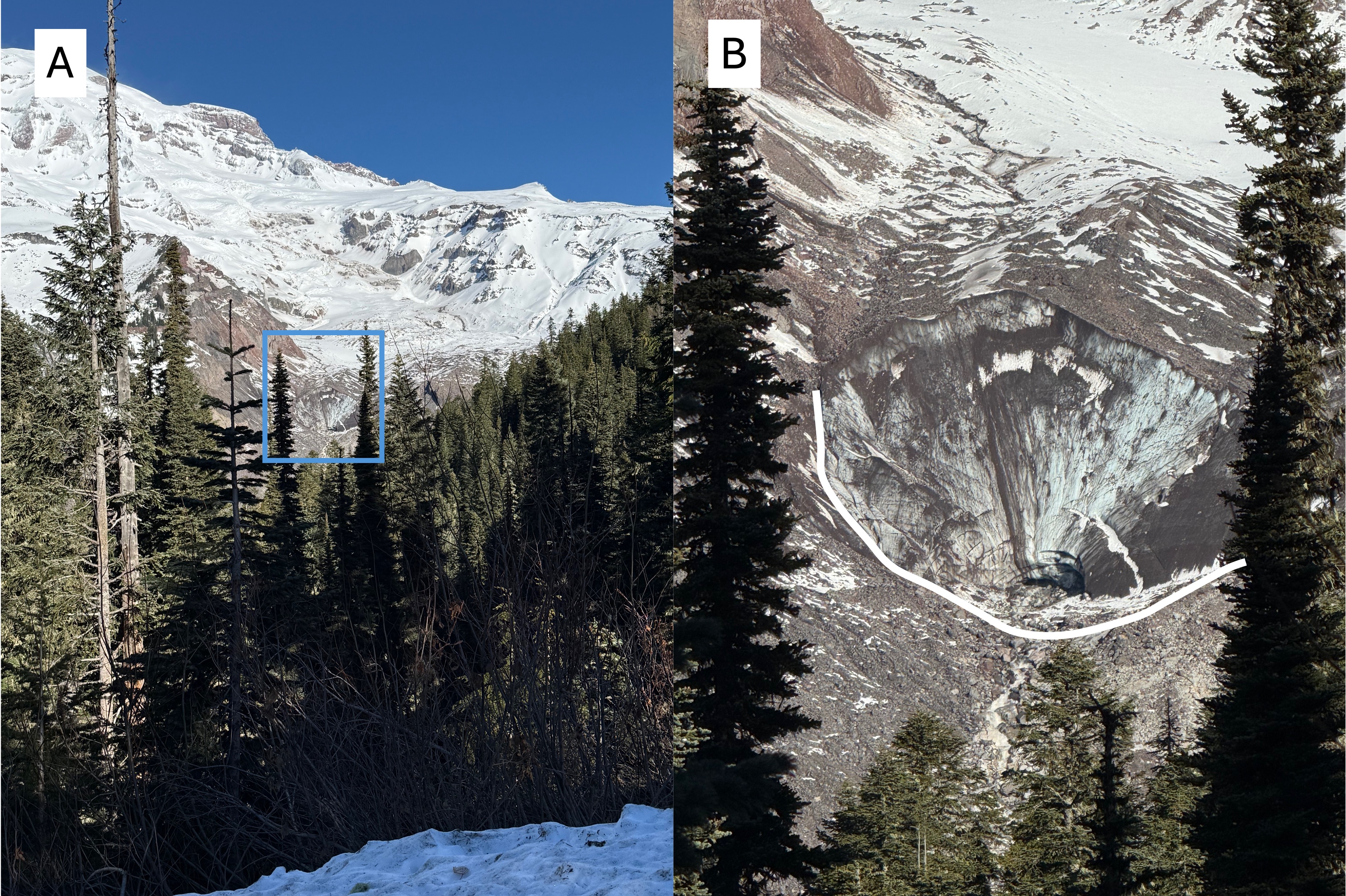

Figure 7. (A) View looking north towards the source of Nisqually Glacier (see Fig. 5 for location), which originates near the peak of Mt Rainier. The area delineated by the blue rectangle is the face of the glacier. (B) Closeup of the face of Nisqually Glacier. The characteristic U-shaped valley carved by glaciers is highlighted in white. Note the dark material within the glacier, probably wind-blown fine sediment. It looks like the face is a couple hundred feet high. I’ve never seen a retreating glacier before, so this is pretty spectacular to me. The Nisqually River originates right here…

Figure 8. View looking upstream along Nisqually River a mile downstream from Fig. 7. This is one of the most stunning photos I’ve ever taken because it reveals geological continuity, from the origin of a glacier 10000 feet higher, to the outwash being transported by a river. Amazing! Note the perfect U-shape where the shadow ends upriver. This area would have been covered by the glacier as recently as 10000 years ago.

Figure 9. Another mile downstream from Fig. 8 the walls of the valley have lowered, and are now rimmed by volcanic flows half-buried by detritus. Evidence of a glacier filling the valley has been erased by collapse of the valley walls. Rounded boulders fill the riverbed. The Nisqually River is overwhelmed by the huge sediment load and opens up new channels to continue flowing.

Figure 10. View looking upstream at the confluence of Nisqually River and Van Trump Creek. There are a couple of interesting features visible in this braided stream bed, less than two miles from the glaciers feeding each branch. The valley is very wide and flat-bottomed because it was carved by glaciers more than 10000 years ago. The large boulders (as large as three feet) covering the entire valley floor were transported by a glacier and became relict after its retreat because the stream flow, even during floods, is too weak to transport and erode them. The Nisqually River is cutting a channel through these relict sediments; the scarp is about eight feet in height. The white line delineates large, surface boulders from subjacent sand and silt with few boulders. Note that the surface boulders stop upstream where the white line curves sharply upward.

Figure 11. Image from 200 feet downstream of Fig. 10, showing a break eroded in the boulder-bar that crosses the stream bed at an angle. During recent heavy rain Nisqually River broke out of its current channel and created a myriad of flow structures such as the longitudinal bars seen in the lower-right of the photo. I think this bedform is actually a terminal moraine marking the maximum advance of a previous glacier–not necessarily the maximum glacial extent during the last two-million years.

Figure 12. (A) Andesite boulder (2 feet across) wet by recent rain shows fine-scale structure. The irregularity of the laminae, and phenocryst distribution, suggest to me that this sample represents ash fall rather than a flow. Magma with the viscosity of peanut butter tends to form smooth lines because it is difficult to penetrate, which would be necessary to create the mixed-up appearance between the lighter and darker shades in the center of the image. (B) Large block (~10 feet long) of intrusive rock similar to that seen at Narada Falls (Fig. 6B), but this is two-miles downstream. This relic was pushed/dragged by a glacier to this location. The white circle indicates where a close-up photo was taken. (C) Close-up (5x) image of the heavy block. It contains quartz (Q), plagioclase/albite feldspar (no orthoclase) (F), and amphibole (Am). My estimate of the composition is: 50% feldspar; 30% quartz; and 20% amphibole. Based on my estimated mineral composition, this would be granodiorite; however, I didn’t differentiate plagioclase and albite feldspar. (The former is darker than the latter.)

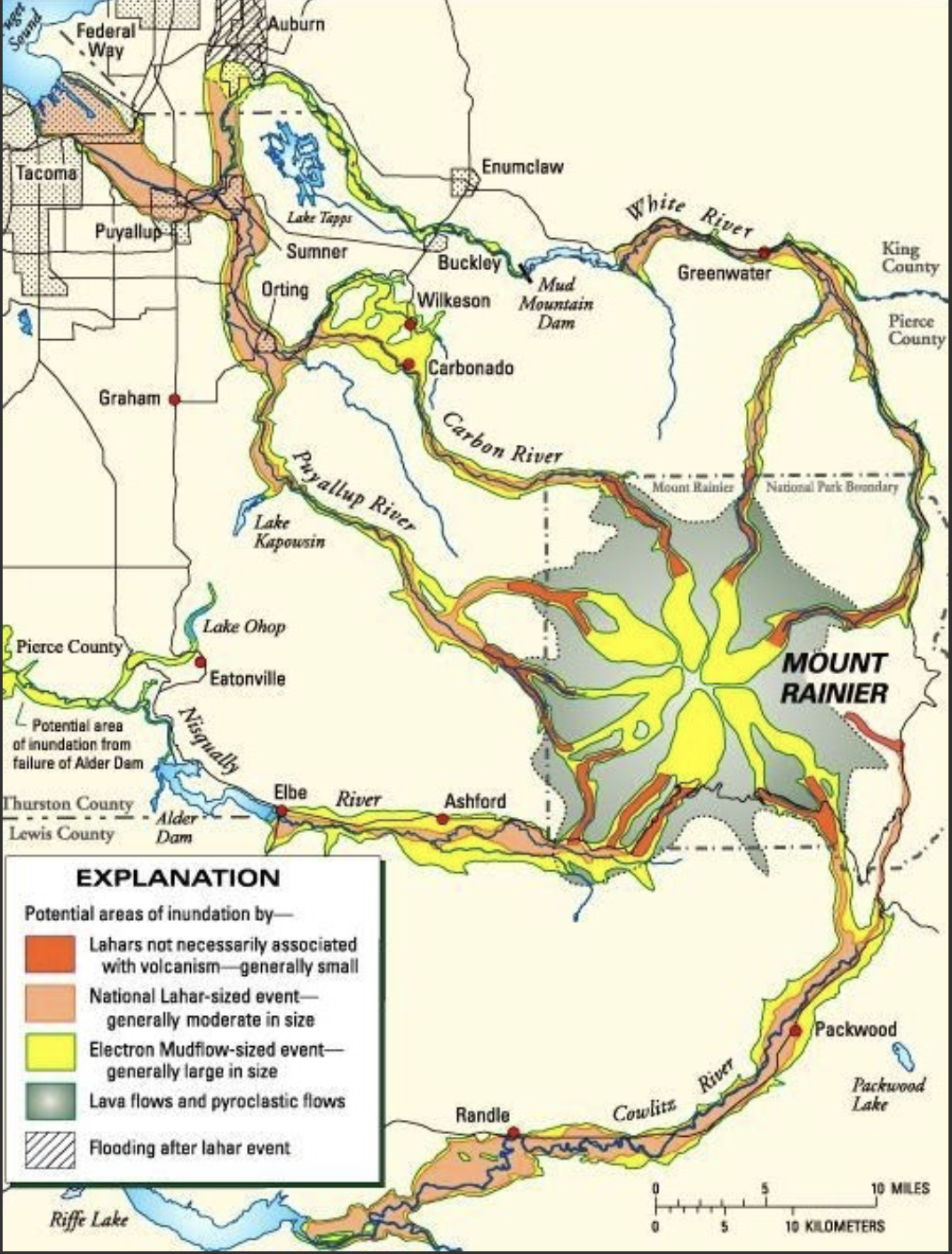

Figure 13. Map of potential volcanic risks associated with Mt Rainier–besides an explosion (e.g. Mt St Helens) and the eruption of ash which would cover a large area, depending on wind direction. Lahars (mud flows fed by all those glaciers) pose the greatest risk because andesite is too viscous to flow more than a few miles from its source.

Summary. I have seen evidence of continental glaciers in the Great Plains, the German Plain, and Ireland, but I never had the opportunity to observe glaciers up close. Alpine glaciers were nothing more than an abstract idea to me, something viewed from a distance.

I’ve looked out over the clouds from the summit of Haleakala crater on Maui, gazed into the cauldron of Kilauea, witnessed the boiling water rising from beneath Yellowstone’s seething caldera. I’ve seen videos of volcanic eruptions in Iceland, but I never imagined putting the glaciers and volcanoes together–right next door!

Usually, geology is observed as a series of images frozen in time, but at Mt Rainier it can be glimpsed as a real-time process that reshapes the earth’s surface–from top to bottom.

What a wild geological ride!

Recent Comments