Gravel Beaches on Vashon Island

This photo of the gravel/mud beach at Fern Cove Nature Preserve reveals a marine delta, fed by Shinglemill Creek. Unlike the mud/sand delta we saw at Dash Point, the sediment here is dominated by rounded gravel and small boulders. Mud, sand and silt form the matrix. All of this material is available from the glacial till that comprises Vashon Island.

The inset map (right) shows the two sites I visited today. Fern Cove is located near the northern tip of Vashon Island whereas Maury Island Marine Park occupies the SE side of an island that is connected to Vashon by a fill zone about 200 yards across (which is eroding away as I type).

Fern Cove Nature Preserve

Vashon Island was logged out, so the beautiful evergreen forests that cover most of the island are all second growth. The state is trying to restore the original habitat, and Fern Cove is a good example; they don’t allow dogs!

I’ve noticed that people in the Pacific Northwest (PNW) appreciate industrial art of a practical nature. I found an example here, in a threatened habitat that is actively being restored. I guess this old truck body isn’t hurting anything; I’ve also noticed that communities in the PNW don’t waste money on unnecessary actions.

This photo shows how the gravel is localized within the delta, forming low nearshore gravel bars. The intervening areas are muddier than I found at Dash Point.

These gravel bars do more than concentrate larger rock fragments. Acorn barnacles encrust the larger ones, which are several inches in diameter. The tidal range is about 7 feet here and the beach is inundated twice daily, so I think these are living. I’ve seen barnacles on large boulders before, but I didn’t know they grew on stones. I guess the wave energy isn’t high enough to disturb them over a life cycle; their larvae must hang around after a storm and find a new rock to inhabit.

On all the beaches I’ve reported on for Rocks and (no) Roads, I’ve never seen this before. This is an active feeding area for sea birds. These are mussels, which the birds grab from a nearby mussel colony on the shallow delta front and drop on exposed gravel during low tide. The shells break open and the birds feast, leaving their dirty dishes behind.

This Western skunk cabbage is just emerging from the wetland surrounding Shinglemill Creek. It will grow leaves up to two feet long, but it makes a beautiful display in the unseasonably warm late winter we’re having in the PNW.

Maury Island Marine Park

On the opposite side of Vashon Island, I visited a gravel quarry that operated for about seventy five years, before being purchased by the state as a park. This is another example of letting nature recover without interference.

This photo looks SSE towards Dash Point. Commencement Bay and Tacoma are visible in the background; a little sunlight is shining on the bay. The cliff has been quarried for 75 years, so the 400-foot vertical face is now a steep incline with a trail that utilizes many switchbacks to reach the shoreline. Let’s see what I found…

There is no mud or sand visible on this beach. I thought that might be a side-effect of so much gravel quarrying, so I walked beyond the limit of the quarry; the substrate didn’t change, but there must be lingering effects after so many decades of preferential sand removal.

After what I saw at Fern Cove, I thought I was prepared for whatever I might find; but I never expected to see clam shells with the hinge lineament intact; this shell even closed after the bird (e.g. gull or crow) has eaten the soft tissue. The shell actually snapped shut after the animal was eaten. Amazing!

This spectacle gives driftwood a whole new meaning. Someone even built a crude shelter in the background from the logs that have collected over the years. There are a lot of trees in the PNW and many of them fall into Puget Sound, ending up all over the place. This looks like what coastal geologists might call a “hot spot”, a location where waves converge during storms.

After a hot climb, even in 45F temperatures, I made it back to the top of the cliff. This area was a barren wasteland in 1975, when the state took over; park authorities and volunteers have worked tirelessly to not only allow recovery, but to keep out invasive species. I think they’re doing a pretty good job.

Summary and Acknowledgments

I learned more biology on this day trip than in my entire life. For example, sea birds eat mussels on muddy beaches and clams on cobblestone ones. They carry the hard shells in the air and drop them on rocks, breaking them open to reveal the animal hiding within. Apparently I arrived at these two beaches just after lunch, when the tide hadn’t cleaned up the dishes yet.

I’m going to pay more attention to fauna and flora in my future posts.

I don’t know anything about biology, so all plants and animals identified in this post came from CoPilot (AKA ChatGPT). I didn’t check their identifications because it wasn’t worth the hours that would have required. This is not a research paper. I’m just going out into the world and observing through my dirty, discolored glasses.

But now I can see living things…

Active Delta Accretion at Dash Point State Park

INTRODUCTION

Puget Sound is a complex water body with many channels and bays, all of them within a couple of hours drive from my home in Tacoma. I haven’t posted much about this because I’ve been overwhelmed by so many active sedimentological processes that are neither marine nor fluvial. But I had to say something about what we discovered on this short trip, less than 30 minutes from our house. Because of the bluffs (~300 feet) surrounding Puget Sound, streams draining into the various inlets and bays are short and relatively steep. There are exceptions of course, such as the Nisqually River, which flows from Mt. Rainier to the southern end of Puget Sound; however, short streams are very common although many of them have been incorporated into municipal storm drainage systems. Today, we found one that was in an almost natural state.

Figure 1. This photo, looking landward from Dash Point beach, says it all: A small stream enters between the two bluffs, each about 200 feet in height, and dumps copious amounts of sand, silt and clay onto a mesotidal shoreline (the tidal range is about 7 feet), where the volume of sediment input overwhelms the nearshore wave and tidal regime to create an expanding delta.

Figure 2. (A) Regional map showing the complex, glacially sculpted, morphology of Puget Sound. The star is approximately where my house is. (B) Google Earth image from about 7000 feet showing Dash Point and the extensive delta being constructed by sediment delivered by a small stream.

Figure 3. The small stream feeding the delta has been confined to a stone-lined channel. This is the entire inflow. The water looks pretty clear, but appearances can be deceiving in the context of sediment transport. This is a bedload-dominated stream, which means that it is mostly transporting sand and silt, and minimal clay particles. The entire area surrounding Puget Sound is constructed of glacial till, which is mostly gravel and sand. A closer examination will confirm this inference.

Figure 4. This is the delta seen in Fig. 2B during an ebbing tide that is near its minimum. The expanse of the delta, at approximately the same tidal height, is seen here at ground level, revealing tidal channels and swales; but the surface is sand and silt with minimal clay restricted to the swales, like those seen in the middle of this photo.

Figure 5. The flattened sea grass serves as a current indicator that perfectly matches the ripple orientation. Note that the tops of the ripples are flattened by the high velocity of the ebbing tide. Waves weren’t very large on this particular day.

Figure 6. Sand bars are constantly being created and destroyed at the fringe of the delta, probably in seasonal cycles. I don’t know where a late February date fits into this cycle. Perhaps I’ll need to return in the summer.

Figure 7. The delta was less symmetric on this February day than the undated image in Fig. 2B. This image looks to the west. It reveals multiple shore-perpendicular sand bars, until the delta is interrupted by shoreline development. Nothing like this was present on the eastern side of the delta on this day. The sediment supplied by the stream in Fig. 3 is being transported westward in this shallow water, but not by waves like we saw on this day, which are perpendicular to the shore.

SUMMARY

Dash Point beach provided a great opportunity to study nearshore sedimentology. Just look at those ripples in Fig. 7! Despite being created and destroyed twice a day, we find rocks preserving similar ripples throughout geologic time.

With so much gravel in the Puget Sound area eroded from the glacial till (gravel and sand), it was exciting to see finer grained sedimentation occurring in real time. Gravel beaches are uncommon in the geologic record whereas rippled, sandy beaches are very common; after all, the previous source of this sand and silt was a glacial till, itself the product of erosion by ice and fluvial transport during the previous twenty-thousand years.

Material is recycled by our tectonically active planet.

Earth abides…

Pinnacle Peak Park: Miocene Andesitic Volcanism

Introduction.

This post examines some of the rocks we discovered while climbing Pinnacle Peak (Fig. 1), a small shield volcano created during the Miocene epoch, between 23 and 5.3 Ma (millions of years ago determined by radiometric dating). The wide range of dates suggests that this volcano remained active for a very long time, producing volcanic material of different types as it released pressure from the magma chamber feeding it. I can’t pin down the dates any better, although they are better known within the geological literature. Thus, my discussion and the model that follows are meant to apply to the entire period of activity.

Figure 1. Pinnacle Peak is about 1000 feet in height. This photo reveals the characteristic low profile of a shield volcano, making it appear smaller because the summit is more than a mile distant; however, note that it is slightly asymmetrical because the southern (right side) slope is lower than the north side.

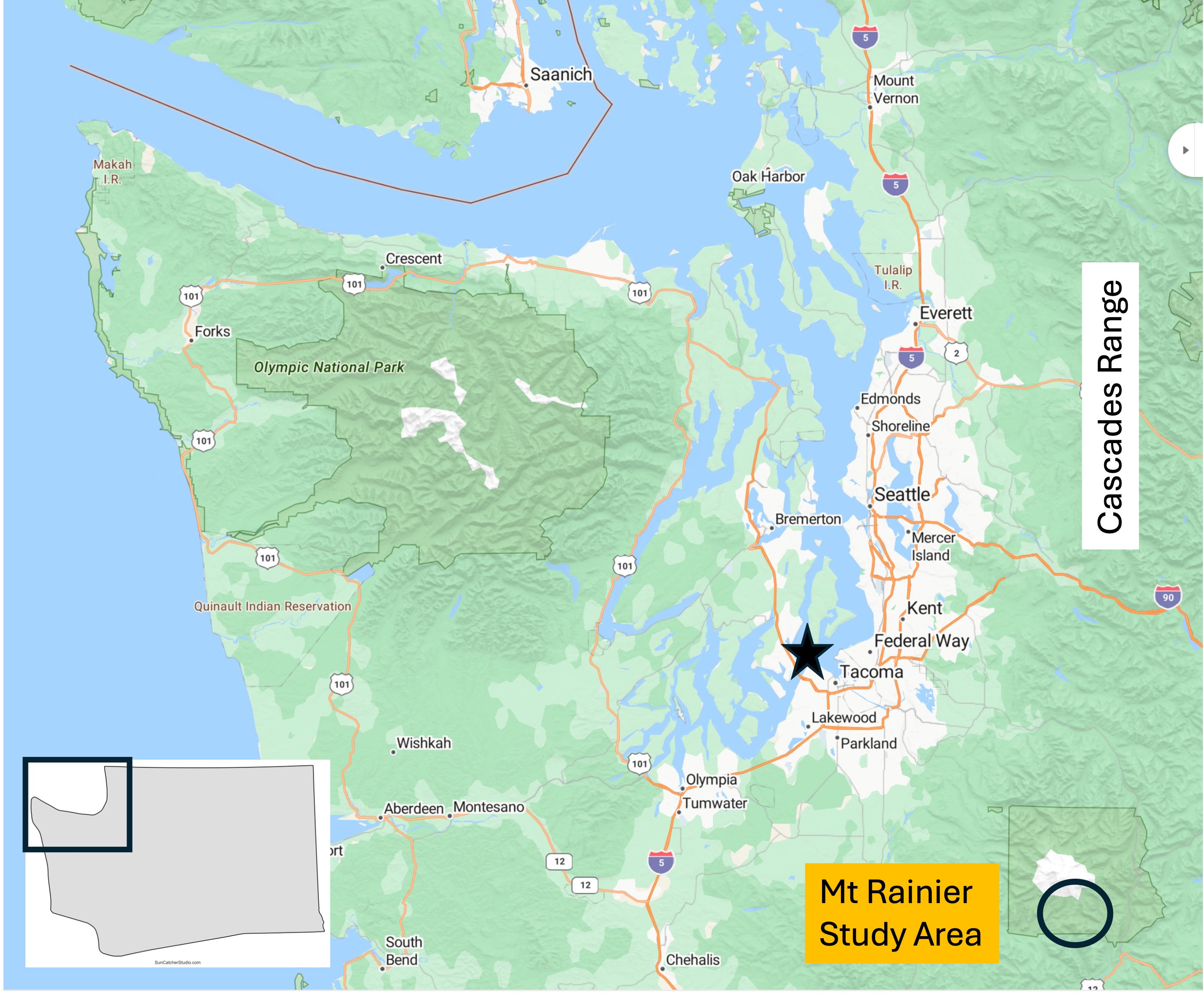

Figure 2. (A) The Pacific Northwest (PNW) base map I will refer to in this series of posts. Tacoma is indicated by a star and Pinnacle Peak park by the circle. It was less than an hour drive on a weekend at 0800; traffic picked up substantially and, by the time we left at about 1130, there was a traffic jam throughout the area because the access roads are small. Go early! (B) The geological map from RockD shows several volcanoes of similar Miocene age standing out in an ocean of glacial till. Note the presence of a deposit of till on the southern slope of the mountain. This was difficult to identify because the main trails followed old logging roads that had been covered with gravel, probably from this till and the White River flood plain below, in which there was active quarrying on the day of our visit. Note the blue arrows at the summit because they will be referred to below.

Observations.

We walked up the Pinnacle Peak Loop Trail counterclockwise, taking photos and noting the geology along the path. However, this is not a geological report but only a casual observation. All dates and rock types are from RockD, a compilation of geological maps produced by uncountable numbers of geologists engaged in active geological field and laboratory research. Thank them for the accessibility of their data, and blame me for any errors in interpreting it.

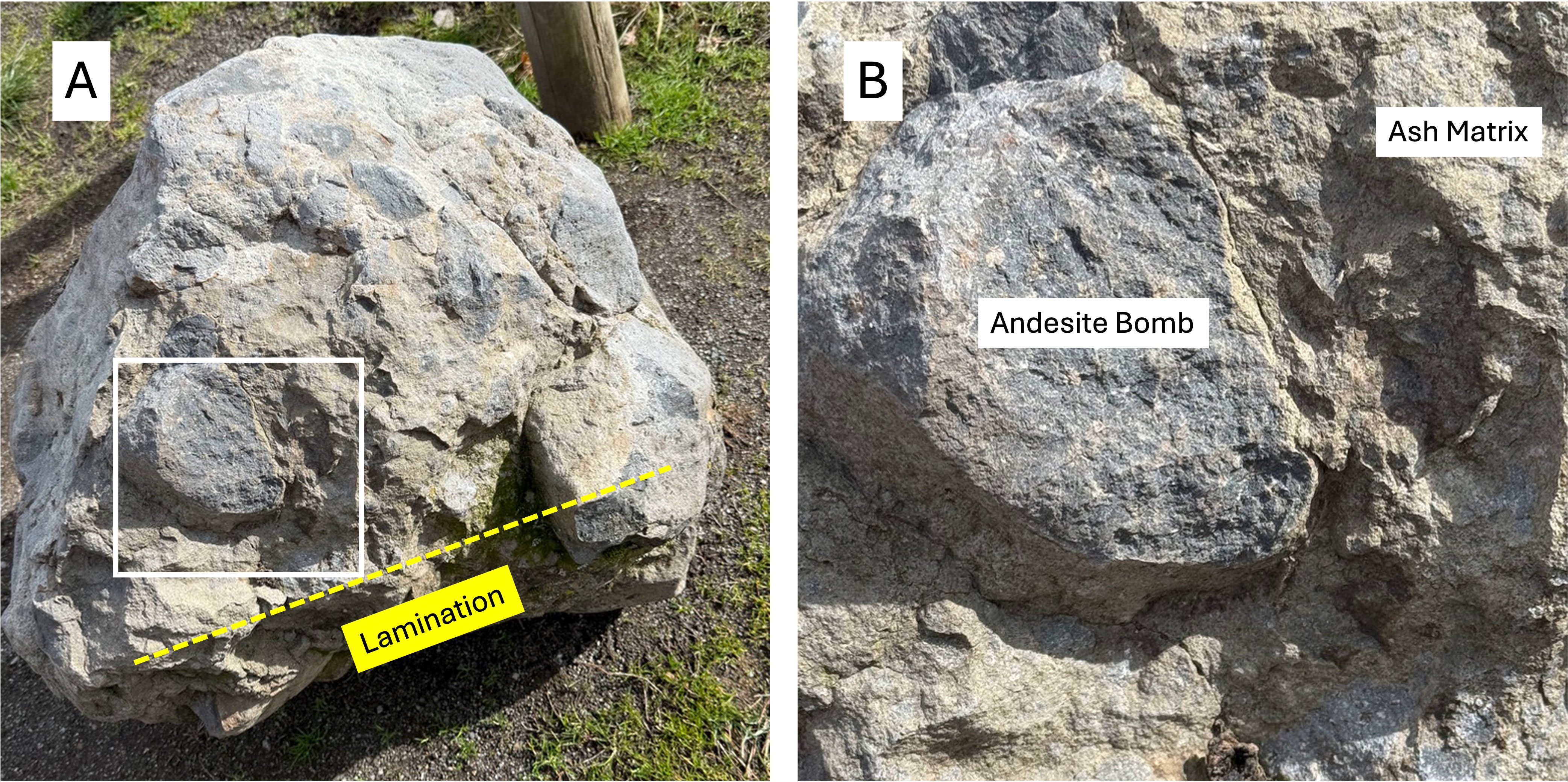

Figure 3. This photo was taken about half-way up the volcano where a road-cut revealed volcaniclastic sediments like we saw at Snoqualmie Falls. This nice exposure reveals a fine matrix of dark material including irregular, but rounded, boulders up to a few feet in diameter. These are volcanic bombs, semi-molten lave blown out of the vent by gas pressure which landed hundreds of feet from the summit.

Figure 4. (A) This boulder of volcanic breccia was placed in the parking lot, probably as an example for public viewing. It is about 3 feet in diameter and contains numerous volcanic bombs, as well as fine lamination near what was its original bottom, as labeled in the figure. These would have been layers of ash with alternating chemical properties that gave them different colors. (B) Close-up showing the contrast between the lighter colored ash matrix and an andesite bomb. Imagine this semi-molten, andesite bomb flying hundreds of yards and landing in still-hot ash. The number of bombs visible in (A) suggest that this was part of a very explosive event.

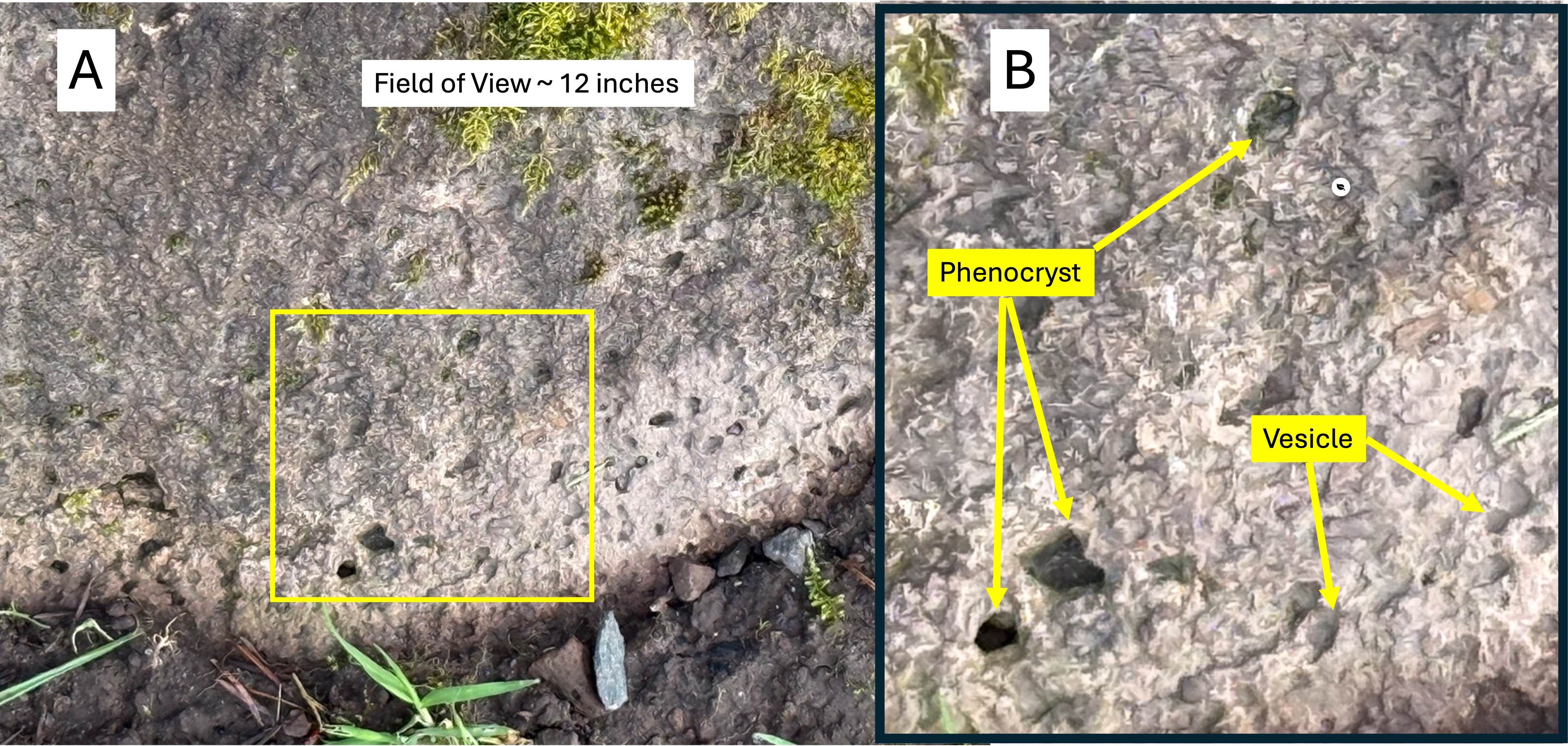

Figure 5. (A) Close-up of a boulder within a semi-hidden exposure of andesite near where Fig. 4 was taken. (B) This close-up reveals phenocrysts (solid mineral crystals) and vesicles (pockets left by escaping volcanic gases). I cannot identify the minerals comprising the phenocrysts, but common ones within andesite are pyroxenes, plagioclase (high-calcium feldspar), hornblende, and biotite. These are all dark minerals that crystallize at higher temperatures than high-silica (Si02) minerals. The specific mineralogy tells volcanologists about the chemistry of the magma chamber feeding the volcano. The vesicles of gas (e.g. CO2, CO, water vapor, sulfur compounds, H2S) are a crude indication of how explosive the magma was; more vesicles implies more explosive potential, especially in andesites, which are more viscous than basalt.

Figure 6. View from near the summit looking south toward the White River. This is a very different perspective of Pinnacle Peak than Fig. 1. The river valley is filled with glacial till (< 1 million years old) that covered all of the volcanic material from the volcano, which stands out today because it was never covered by ice.

Figure 7. Photo taken on the SE side at the top of Pinnacle Peak (blue arrow in Fig. 2A). These horizontal rocks are not boulders, but instead the ends of columnar joint blocks of andesite. They are less than one foot in diameter; most of them are hexagonal, but irregular shapes are also present. They form when lava cools slowly enough to allow this kind of crystallization to occur, but rapidly enough that the lava doesn’t form massive beds.

Figure 8. Photo of columnar andesite near the summit on the NNW side. These are much larger in diameter than those seen in Fig. 7. Columnar jointing is usually oriented with the ends vertical, but this isn’t necessarily required because gravity is not the dominant force; chemical bonds between the individual minerals determines the development and size of columnar joints. As long as the “top” of the lava flow (facing the camera in this photo) is exposed to the atmosphere, they can form. I reported on incredible examples of this in my post on Organ Pipes National Park near Melbourne, Australia.

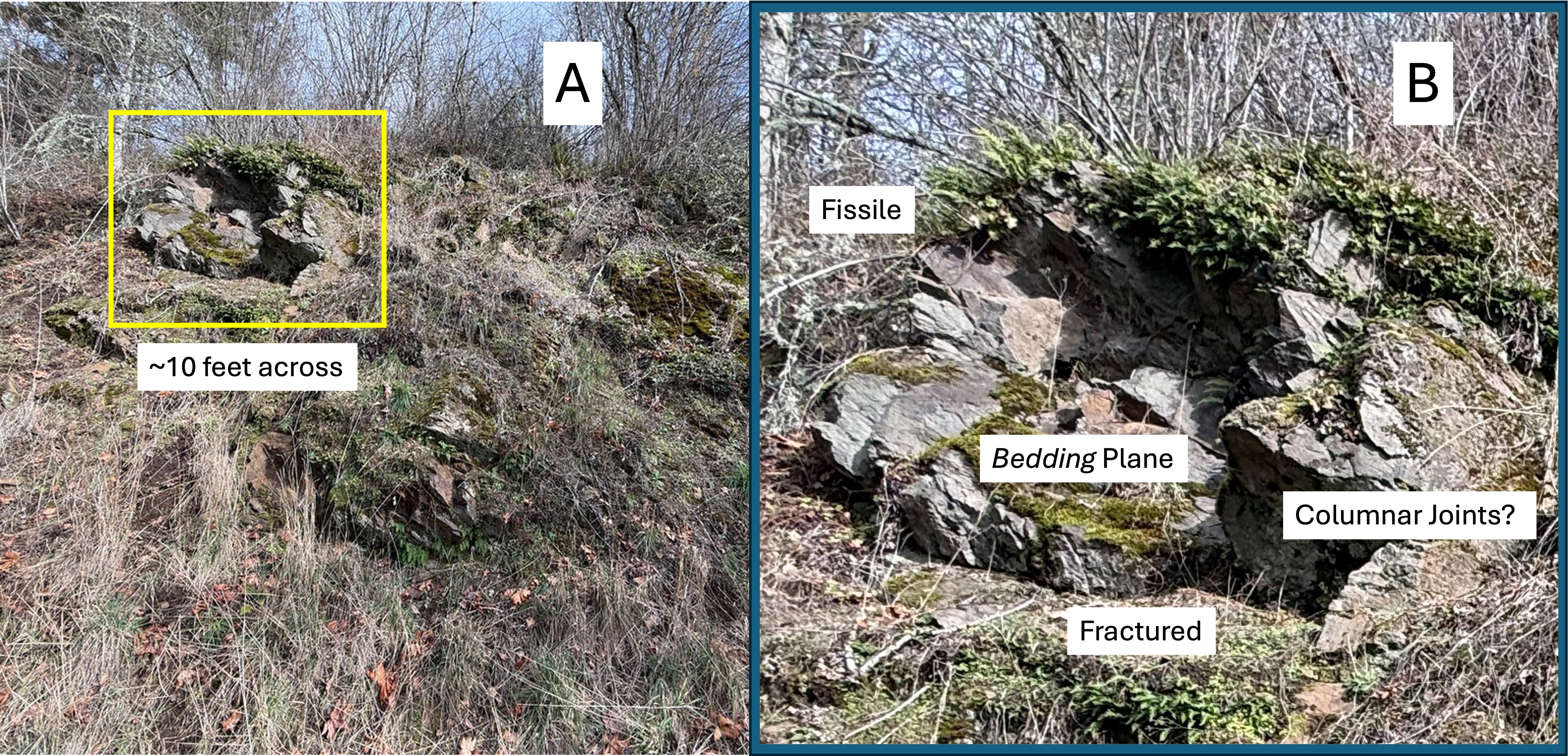

Figure 9. This exposure, from further down the south slope of Pinnacle Peak, reveals blocky lava that seems to be bedded, with bedding planes dipping away and to the right of the camera. No columnar jointing is visible, and the rocks are solid. This could be an outcrop of sandstone if it weren’t for the grayish color. Maybe limestone?

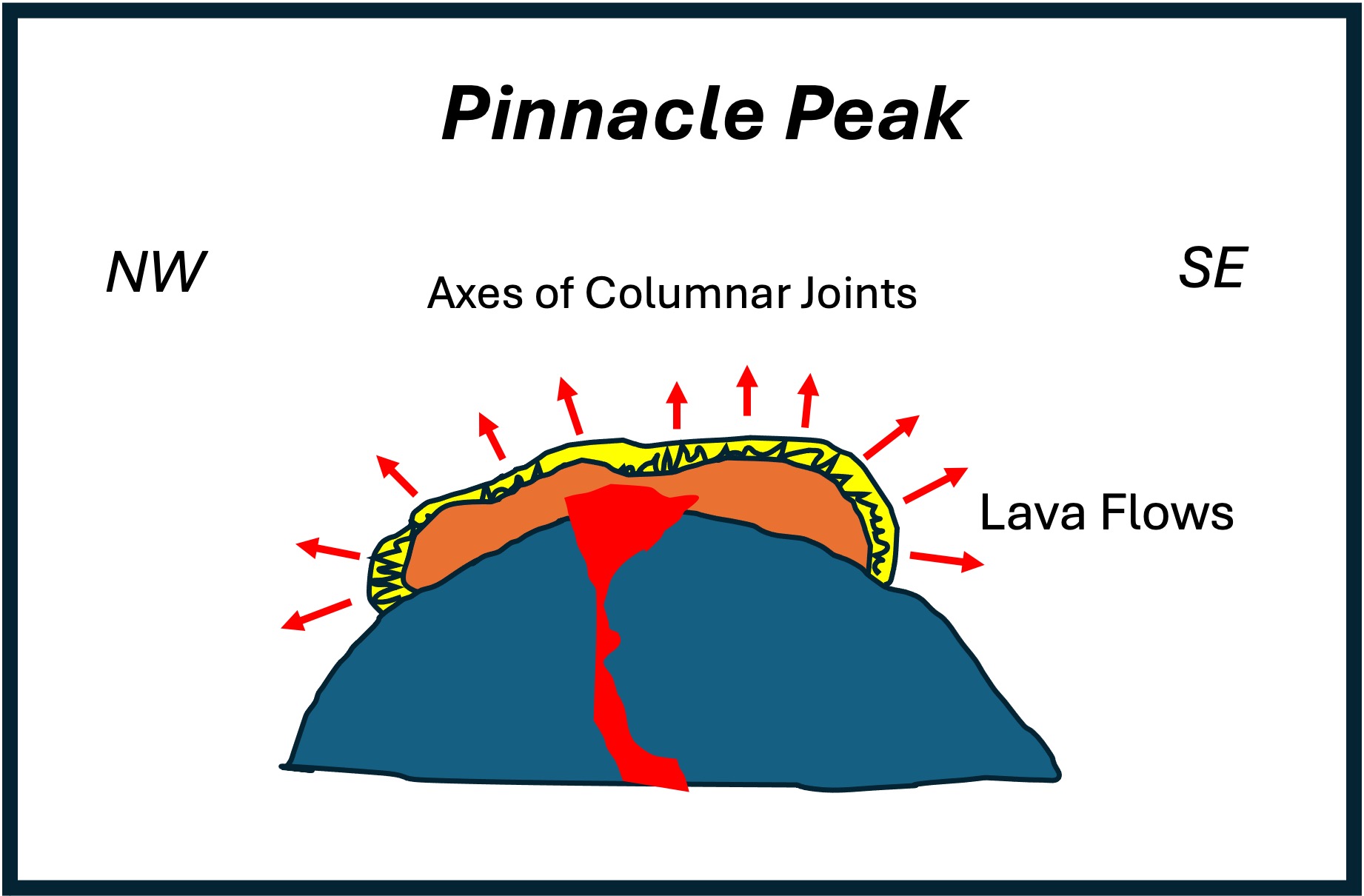

Figure 10. (A) Exposure of andesitic lava that looks much the worse for wear than anything I’ve seen before on this field trip. (B) Close-up of the exposure outlined in (A) that reveals a jumbled mass of lava that reveals several secondary textures: contamination and preferential erosion along “bedding” planes (fissility); irregular and tilted bedding planes; fine-scale fracturing and weathering (fractured); and blocks with a hint of hexagonal form (columnar joints). This was near the bottom of the volcano and the rocks are presumably older than those seen in Figs. 3, 7, 8, and 9; in other words this photo implies that eruption style was not uniform throughout this volcano’s lifetime. I further suggest that, over the lifetime of this volcano’s active period, the magma chamber became more stable, and thus the eruptions more predictable.

Figure 11. All of the textures, mineralogy, and fabric of the rocks comprising Pinnacle Peak fall within the expected composition of a shield volcano, except for the horizontal columnar jointing seen in Figs. 7 and 8, which point in opposite directions (NW and SE) even though the lava erupted directly from a rather small outlet (~200 feet in diameter). I didn’t understand what I saw at Organ Pipes National Park, but I let it go; now that I’ve encountered similar textures again, I want to have at least a naive understanding of how lava can form structures similar to a wilted plant. This is my model. The purple represents thousands of lava flows, volcaniclastic deposits, etc; the red is the lava just before the eruption(s) represented by Figs. 7 and 8; and the yellow is a thin layer of viscous lava that flowed out over a slightly older deposit. This last eruption wasn’t immediately covered by more lava and it cooled according to the laws of thermodynamics. In other words, it formed columnar joints, which are represented by the squiggly lines. The red arrows point to toward the “top” of the flow at every point; as you can see, the “top” isn’t always pointing towards the sky. This model is based on simple thermodynamics and mineralogy–I assume that the lava is a homogeneous mixture of the components of andesite (e.g. quartz, feldspar, pyroxene), which are cooled only by their exposure to the atmosphere. The different diameters in the columns (compare Figs. 7 and 8) suggests that this is an oversimplification. Nevertheless, it makes sense to me.

SUMMARY.

I had a great time climbing Pinnacle Peak and I learned something new from the rocks that surround and support us. A large mountain range like the Cascades doesn’t appear overnight. Subduction along the NW coast of N. America continued, interrupted by collisions with offshore continents, from 200 Ma to the present, creating multiple mountain ranges which created the Pacific Northwest. A small volcano like Pinnacle Peak would have burned out in a few million years. The range in age is based on stratigraphy, and the absence of funding/geologists to date rocks from every minor volcano in a major subduction zone, leaves me to apply common sense.

Pinnacle Peak erupted about 5 Ma, based on the physical status of the summit. It sputtered for a few hundred-thousand years as the magmatic system decompressed; eventually the magma chamber, or a subsystem of pathways, gave a last gasp. The columnar jointing we saw today suggests that this final eruption consisted of some spitting and then the appearance of timid lava, flowing a few-hundred yards from the summit (Fig. 11). That is what we saw on today’s field trip.

That’s my story…

Snoqualmie Falls: Eocene Volcanism in the Cascades Subduction Zone

INTRODUCTION.

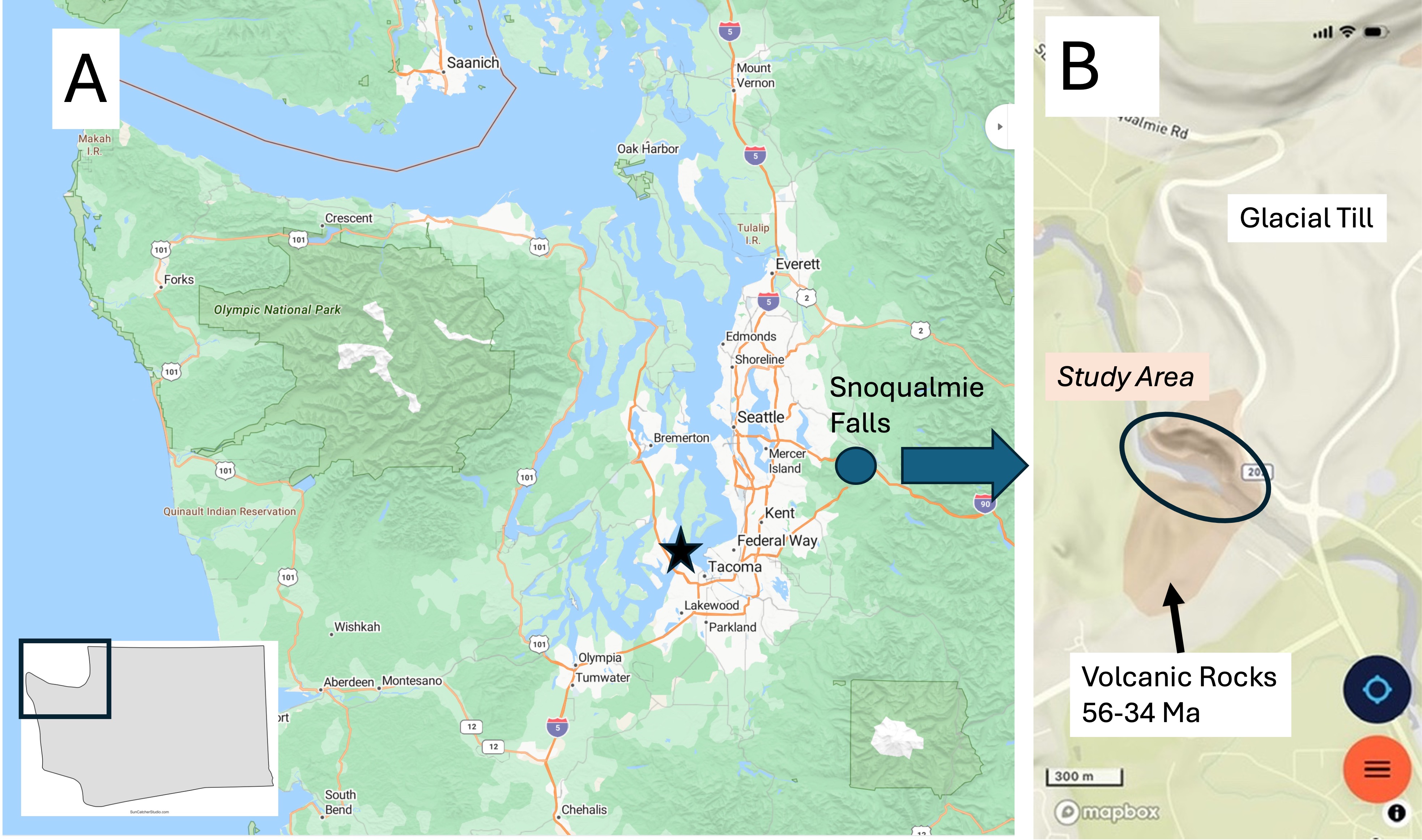

Figure 1. (A) Snoqualmie Falls is less than an hour from Tacoma, in the foothills of the Cascades Range of volcanic mountains. (B) The geologic map doesn’t show much besides glacial till, except around the falls (circled). I recently discovered that the Cascades is one of the youngest mountain ranges in the world, and it includes many active volcanoes that are part of the Pacific “Ring of Fire.” Most of the volcanic rocks were erupted from fissures and small volcanoes during the Eocene epoch (56-34 my ago). The active volcanoes (e.g., Mt St Helens and Mt Rainier) are less than a million years old, reflecting renewed magmatism at depth.

Observations

Figure 2. The 270 foot drop over Snoqualmie falls encouraged a private consortium to construct the world’s first subterranean hydroelectric power plant. The turbine outflow is visible at the bottom-center of this image. Note the massive wall of volcanics in the center of the photo. The exact origin of the falls is unknown because there are no major faults in the area, although the entire region is cross-cut by faults. The default narrative is a combination of glacial scour and natural variability in the rock composition and thus strength. For example, Niagara Falls was also formed during the last ice age along a natural escarpment, but the rocks comprise hard dolomite over soft shale; this combination led to undercutting and continuous upstream erosion at ~1 foot/year. All of the rocks at Snoqualmie falls are andesitic; however, note that the cliff ends to the right of the photo and a slope emerges. This could be a clue…

Figure 3. The riverbank several hundred yards downstream from the falls reveals a rock unit comprising large boulders in a matrix that erodes to form sand and mud.

Figure 4. A close-up of the downstream bank reveals boulders several feet in diameter protruding from the cliff face. As the softer matrix material erodes, these blocks fall into the river. These are volcanic bombs–partially molten lava that solidifies in flight before landing far from the vent; volcanic bombs up to 20 feet in diameter have been ejected 2000 feet from the vent in volcanoes in Japan. Because they are soft, these ejecta become smooth during their flight and are sometimes flattened when they land. Consequently they can look like rounded boulders and cause confusion when found in a river. The giveaway is the matrix in which they are embedded. However, the story is more complicated than that…

Figure 5. A boulder of volcaniclastic rock exposed in the river channel, rounded by collisions with other rocks. This sample is six-feet long. Note the mixture of tephra of different sizes and shapes. Each fragment was semi-molten when it was ejected from the vent; of course, it landed in ash rather than on hard ground. However…this sample comprises a matrix that is solid, not crumbly like the cliff base seen in Fig. 3; the only explanation I can think of is that the matrix varied substantially over time and space. In other words, this block represents an eruption of extremely hot ash, which formed a welded tuff (aka ignimbrite), encasing the tephra in stone immediately after eruption. The friable matrix in Fig. 4 wasn’t as hot; it is even possible (albeit unlikely) that this block was itself ejected from a younger eruption and became a volcanic bomb. I’m not putting any money on that; my point is that volcanic eruptions are very dynamic, and the rocks we see today represent millions of years of magma chamber depressurization.

Figure 6. This eight-foot boulder contains fine layering in its lower half. This suggests that the tephra landed in a layer of ash that was so hot it became a welded tuff, even as eruptions continued intermittently. This block is NOT a volcanic bomb (despite my speculation in Fig. 5); it is a sample of the volcanic debris erupted from a vent (including volcanic bombs), which was subsequently eroded from somewhere within the local area, representing an eruption so hot it created an ignimbrite. This sample (as well as Fig. 5) thus reflects eruption and initial deposition, followed by erosion in a stream–giving them a rounded appearance similar to that of the tephra they contain; thus the term volcaniclastics.

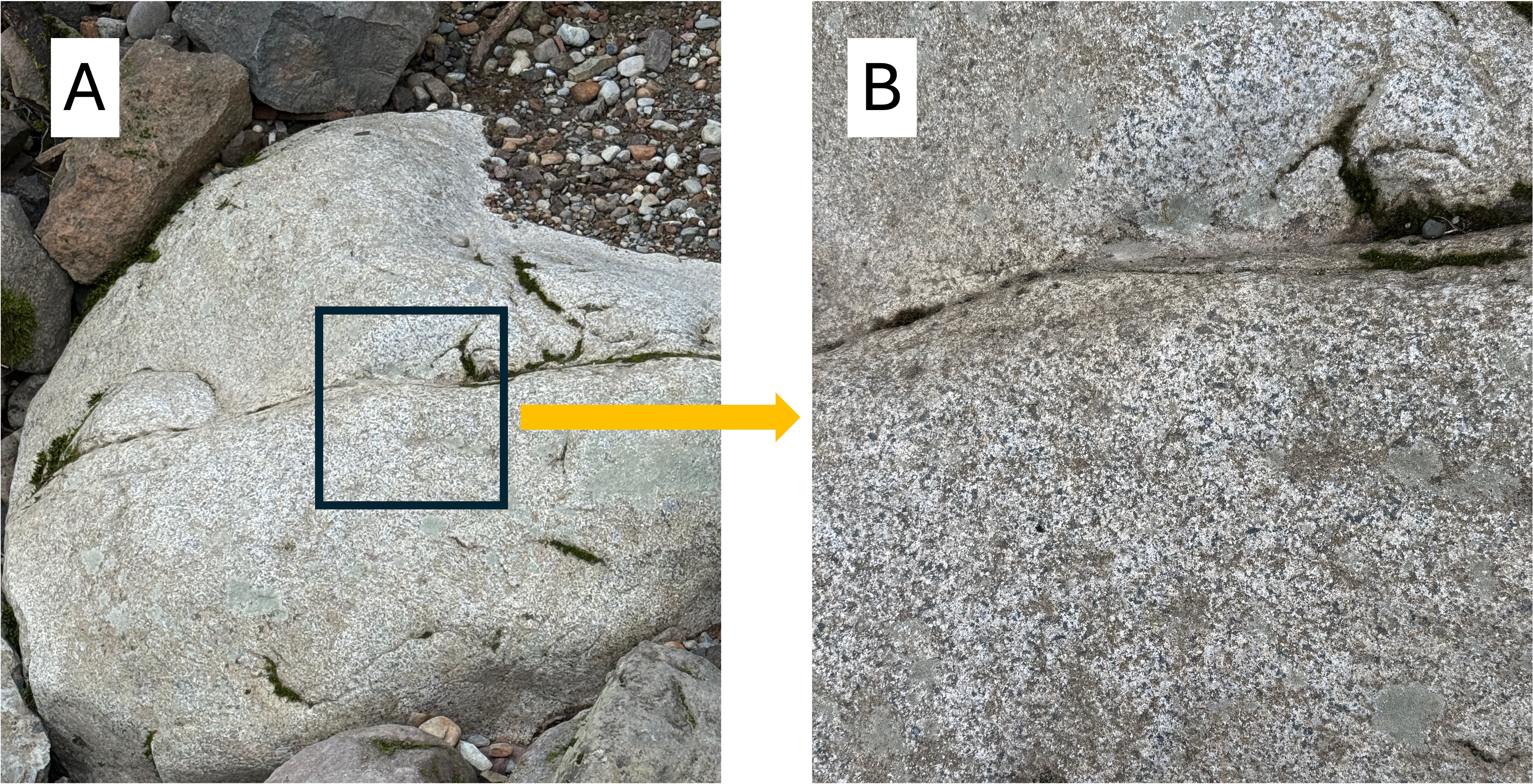

Figure 7. This is where this field trip got interesting. (A) This rounded boulder (4 feet across) doesn’t look like the volcanic rocks in Figs. 5 and 6. It contains no tephra or lamination. What’s going on? (B) A close-up photo reveals this to be an intrusive rock; individual mineral grains are visible, giving it a stippled appearance. It isn’t as coarse-grained as a classic granite with large crystals visible to the unaided eye; however, it isn’t extrusive either (microscopic grain size). This rock formed within a shallow magma chamber (possibly a dike or sill) in which the molten magma cooled faster than a deeply buried granite, but slower than an extrusive rock. This is common within volcanic terrains in which fresh magma is often injected into pre-existing layers of extrusive rocks. This sample is relatively fresh (i.e., no biological surface coverings) and thus its composition can be guesstimated: the whitish areas are feldspar (albite and plagioclase) that contains sodium and calcium, but not potassium; they comprise approximately half of the minerals; the darker grains are (probably) hornblende and biotite; a suggestion of gray implies some quartz. The relatively low quartz content suggests this is diorite. Diorite is the intrusive equivalent of andesite; it follows that the thickness of volcanic rocks visible in Fig. 2 is andesite, which is common in subduction zones. The bottom line is that this sample is NEITHER a volcanic bomb nor a block of the tephritic, extrusive rock seen in Figs. 3 and 4. It was probably emplaced within layers of older volcanics and later eroded, eventually falling into the river, where it was rounded by collisions with other boulders.

SUMMARY.

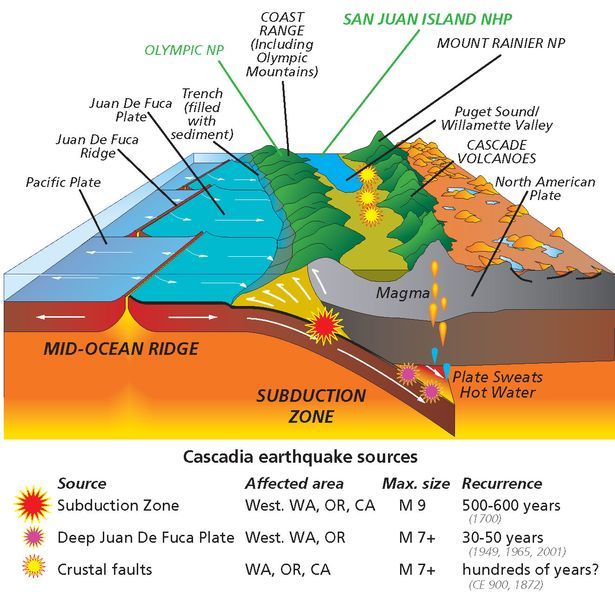

Figure 8. Snoqualmie falls is located at the northern end (top) of this schematic, within the second belt of mountains (green). The history of subduction along the Pacific Northwest (PNW) is uncertain because of intermittent subduction and crustal thickening. When Pangea split along what is now the mid-Atlantic ridge system about 200 my ago, the North American plate began a complex history of either riding over the Juan de Fuca oceanic plate or colliding with various islands and micro-continents that were in the way. By these disparate accretionary mechanisms, the west coast of N. America propagated westward hundreds of miles, at least from Montana. Jumping ahead to 50 my ago, a new round of subduction began, characterized by multiple vents, fractures, and volcanoes; these produced the older rocks of the Cascades. The Columbia plateau basalts were erupted about 15 my ago–Act II in this ongoing geological opera; the third act (using a simple theatrical model) was the appearance of multiple volcanoes fed by localized magmatic chambers in the last million years. This geological opera is complicated by at least two distinct events: (1) the San Andreas transform fault and associated strike-slip faults from Mexico to Canada, which together transport crustal blocks to the NW (i.e. Alaska); and (2) the anomalous mantle plume associated with the Yellowstone caldera.

Unlike the ancestral Appalachian mountains, whose geological history must be inferred from fragmentary and ambiguous data, the PNW geo-opera is being performed before our eyes.

Think about it–Mt St Helens wasn’t an outlier…anything can happen in the PNW…

Quaternary Geology on Mt. Rainier

Figure 1. View of Mt Rainier from the west. At 14410 feet, it is the most prominent peak in the contiguous United States. It has 28 glaciers, with the largest total surface area in the lower states–35 square miles. Mt Rainier is a stratovolcano, composed of andesitic lava (rather than basalt), material ejected from the summit, and ash layers. This type of volcano is commonly found in subduction zones; they tend to have explosive eruptions (e.g. Mt Saint Helens). The oldest rocks on Mt Rainier are about 500,000 years old. It is active and listed as a decadal volcano–one of the most dangerous volcanoes in the world. Its last major eruption, accompanied by caldera collapse, was 5000 years ago, but minor activity was noted during the nineteenth century.

Figure 2. From my home in Tacoma (star) it’s a two-hour drive to Mt Rainier National Park. It is part of the Cascades Range, which comprises many well-known volcanoes like Mt Baker, Mt St. Helens, and Mt Hood.

Figure 3. This photo was taken on the south flank at an elevation of about 5400 feet, near the visitor’s center. It was a beautiful day and there were a lot of people preparing for some cross-country skiing on a couple of feet of snow. From this elevation it takes 2-3 days to reach the summit, almost 9000 feet higher. It’s hard to imagine it being so high and taking so long to reach.

Figure 4. These southern volcanic mountains are part of the Tatoosh Range, with peaks of about 6600 feet. Most of the volcanic rocks comprising these mountains are andesite, intermediate in composition between basalt and rhyolite. It is also very viscous, behaving like peanut butter and thus not flowing well. Andesite is commonly found at convergent plate boundaries where it is thought to result from mixing of basalt (from the oceanic crust), continental crust, and sediments accumulated in the accretionary prism.

Figure 5. Map of the 28 glaciers on Mt. Rainier. The glaciers fill canyons and valleys that were partly cut by ice. Figure 3 shows a smooth mountain, but in reality most of the smooth areas are the surfaces of glaciers. We’ll look at one below. The ellipse indicates the area discussed in this post.

Figure 6. (A) Narada Falls interrupts the descent of Paradise River, fed by Paradise Glacier (see Fig. 5 for location), making it drop a couple hundred feet over a thick layer of andesite. Andesite tends to form blocky flows, as shown in the right side of the photo, where the water seems to be climbing down steps. (B) Possible contact between younger volcanic and older intrusive rocks. Igneous activity within the area has been continuous for at least 50 my, during which time erosion has exposed older intrusive rocks like this granodiorite, which is part of a pluton intruded between 23 and 5 Ma. It is important to keep in mind that the volcanic rocks originated in plutons (magma chambers) emplaced miles beneath the surface. As they are exposed, new volcanoes form as more magma is injected into the shallow crust in a continuous process. (C) Differential weathering has accentuated layering in this volcanic rock, which was probably created by a series of ash layers deposited in quick succession–geologically speaking.

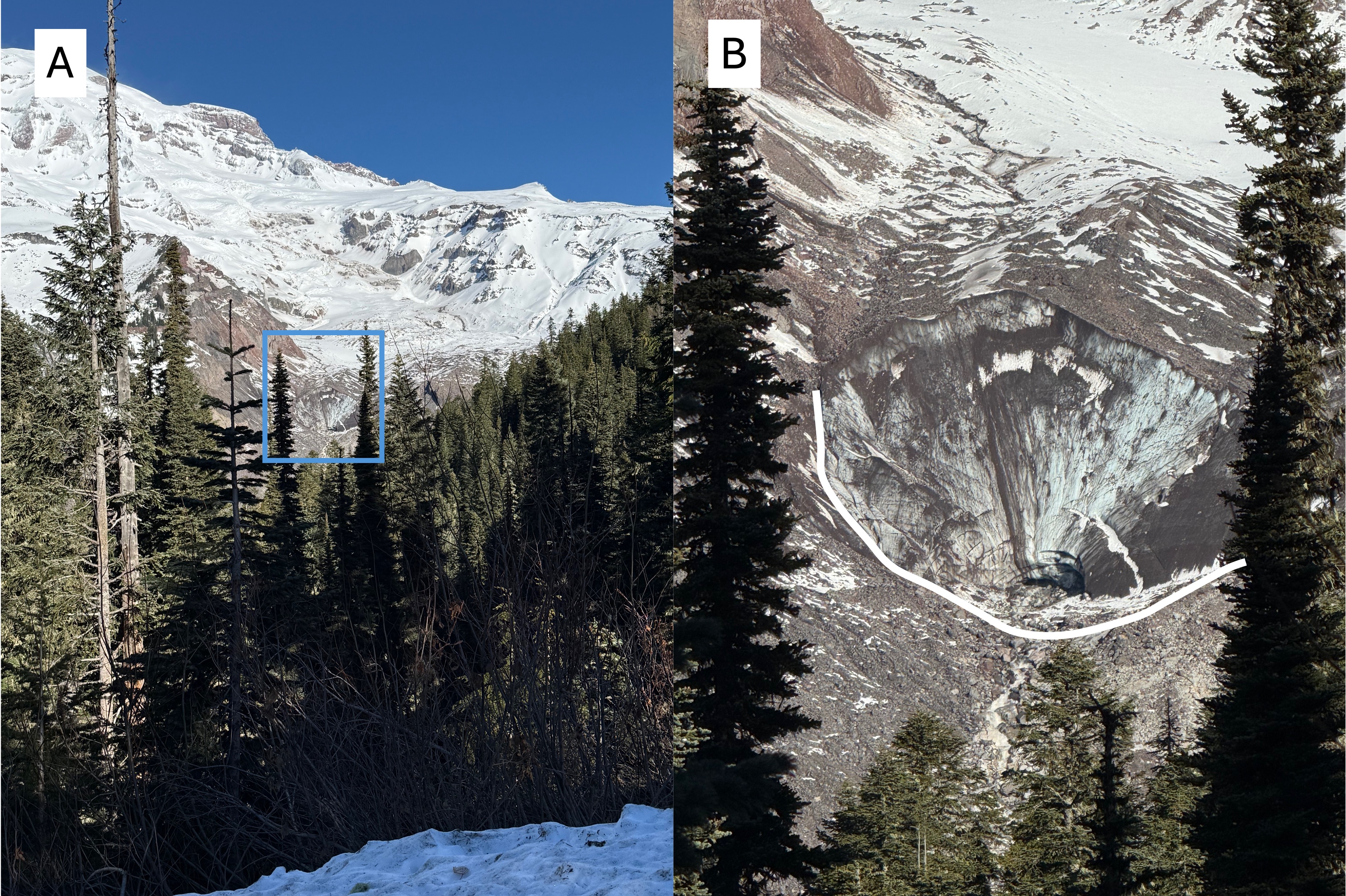

Figure 7. (A) View looking north towards the source of Nisqually Glacier (see Fig. 5 for location), which originates near the peak of Mt Rainier. The area delineated by the blue rectangle is the face of the glacier. (B) Closeup of the face of Nisqually Glacier. The characteristic U-shaped valley carved by glaciers is highlighted in white. Note the dark material within the glacier, probably wind-blown fine sediment. It looks like the face is a couple hundred feet high. I’ve never seen a retreating glacier before, so this is pretty spectacular to me. The Nisqually River originates right here…

Figure 8. View looking upstream along Nisqually River a mile downstream from Fig. 7. This is one of the most stunning photos I’ve ever taken because it reveals geological continuity, from the origin of a glacier 10000 feet higher, to the outwash being transported by a river. Amazing! Note the perfect U-shape where the shadow ends upriver. This area would have been covered by the glacier as recently as 10000 years ago.

Figure 9. Another mile downstream from Fig. 8 the walls of the valley have lowered, and are now rimmed by volcanic flows half-buried by detritus. Evidence of a glacier filling the valley has been erased by collapse of the valley walls. Rounded boulders fill the riverbed. The Nisqually River is overwhelmed by the huge sediment load and opens up new channels to continue flowing.

Figure 10. View looking upstream at the confluence of Nisqually River and Van Trump Creek. There are a couple of interesting features visible in this braided stream bed, less than two miles from the glaciers feeding each branch. The valley is very wide and flat-bottomed because it was carved by glaciers more than 10000 years ago. The large boulders (as large as three feet) covering the entire valley floor were transported by a glacier and became relict after its retreat because the stream flow, even during floods, is too weak to transport and erode them. The Nisqually River is cutting a channel through these relict sediments; the scarp is about eight feet in height. The white line delineates large, surface boulders from subjacent sand and silt with few boulders. Note that the surface boulders stop upstream where the white line curves sharply upward.

Figure 11. Image from 200 feet downstream of Fig. 10, showing a break eroded in the boulder-bar that crosses the stream bed at an angle. During recent heavy rain Nisqually River broke out of its current channel and created a myriad of flow structures such as the longitudinal bars seen in the lower-right of the photo. I think this bedform is actually a terminal moraine marking the maximum advance of a previous glacier–not necessarily the maximum glacial extent during the last two-million years.

Figure 12. (A) Andesite boulder (2 feet across) wet by recent rain shows fine-scale structure. The irregularity of the laminae, and phenocryst distribution, suggest to me that this sample represents ash fall rather than a flow. Magma with the viscosity of peanut butter tends to form smooth lines because it is difficult to penetrate, which would be necessary to create the mixed-up appearance between the lighter and darker shades in the center of the image. (B) Large block (~10 feet long) of intrusive rock similar to that seen at Narada Falls (Fig. 6B), but this is two-miles downstream. This relic was pushed/dragged by a glacier to this location. The white circle indicates where a close-up photo was taken. (C) Close-up (5x) image of the heavy block. It contains quartz (Q), plagioclase/albite feldspar (no orthoclase) (F), and amphibole (Am). My estimate of the composition is: 50% feldspar; 30% quartz; and 20% amphibole. Based on my estimated mineral composition, this would be granodiorite; however, I didn’t differentiate plagioclase and albite feldspar. (The former is darker than the latter.)

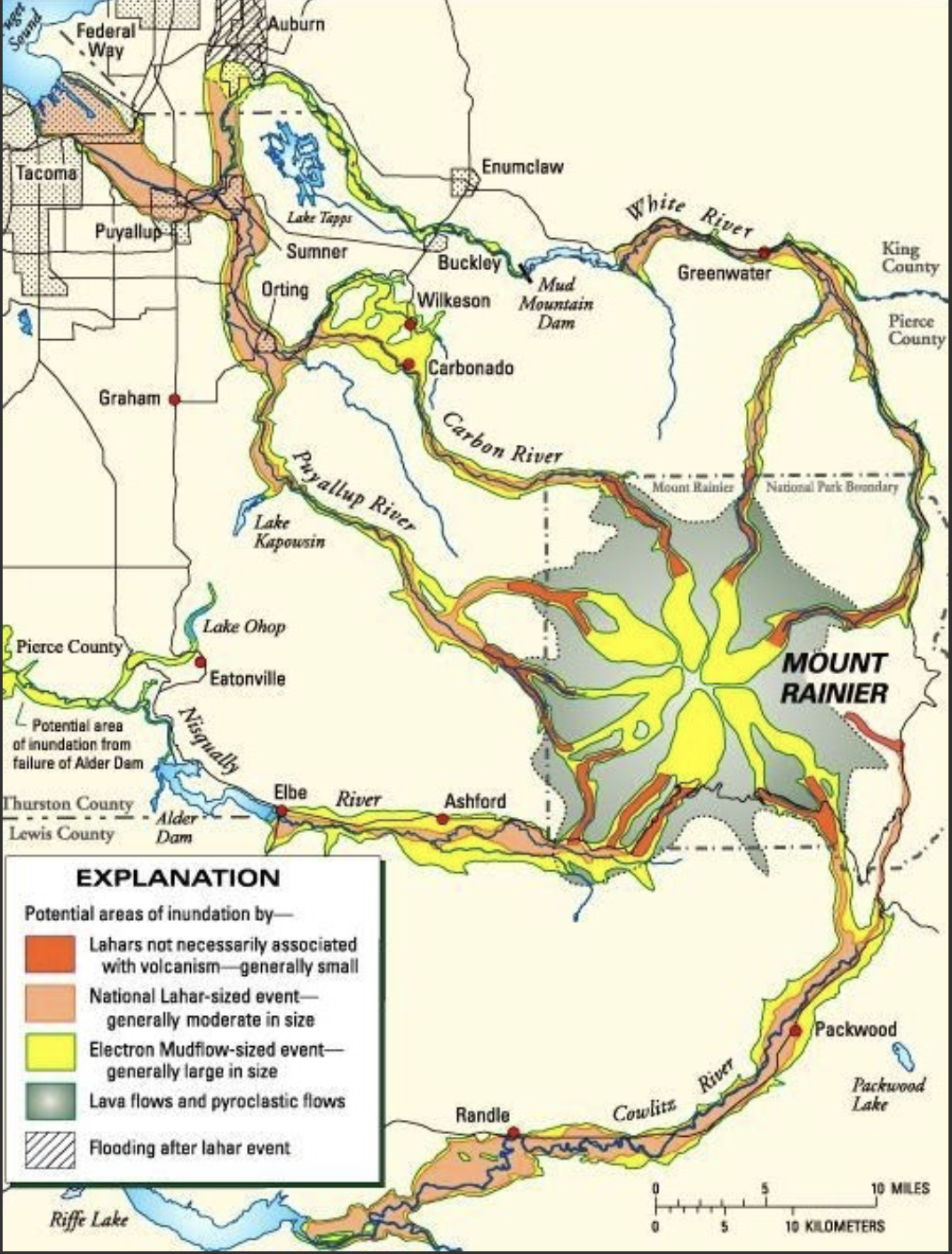

Figure 13. Map of potential volcanic risks associated with Mt Rainier–besides an explosion (e.g. Mt St Helens) and the eruption of ash which would cover a large area, depending on wind direction. Lahars (mud flows fed by all those glaciers) pose the greatest risk because andesite is too viscous to flow more than a few miles from its source.

Summary. I have seen evidence of continental glaciers in the Great Plains, the German Plain, and Ireland, but I never had the opportunity to observe glaciers up close. Alpine glaciers were nothing more than an abstract idea to me, something viewed from a distance.

I’ve looked out over the clouds from the summit of Haleakala crater on Maui, gazed into the cauldron of Kilauea, witnessed the boiling water rising from beneath Yellowstone’s seething caldera. I’ve seen videos of volcanic eruptions in Iceland, but I never imagined putting the glaciers and volcanoes together–right next door!

Usually, geology is observed as a series of images frozen in time, but at Mt Rainier it can be glimpsed as a real-time process that reshapes the earth’s surface–from top to bottom.

What a wild geological ride!

Deception Pass: Ophiolite or Volcaniclastic Sediments?

Now that I have a general idea of the geologic history of Northwest Washington (NWA) it’s time to start filling in the blanks. I immediately found a discrepancy in the rocks found on the northern end of Whidbey Island and the adjacent peninsula (Fig. 1): some authors identified these rocks as ophiolite–pieces of ocean crust that contain evidence of extrusion at mid-ocean ridges. Let’s see what I found.

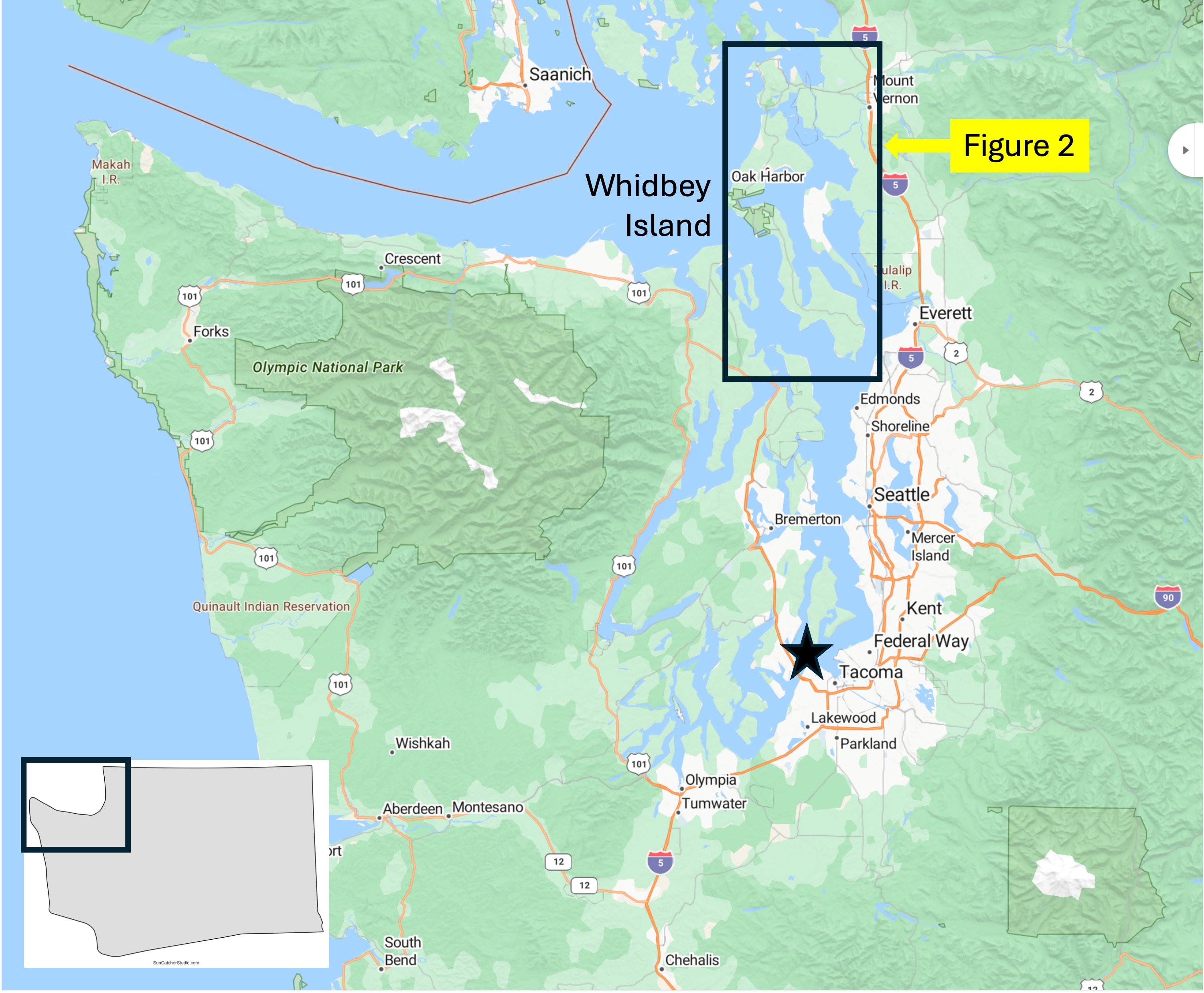

Figure 1. Whidbey Island is a large island that is almost completely covered by glacial sediments. Its elevation varies from less than 100 feet above msl (mean sea level) to almost 400 feet, probably reflecting the presence of terminal morraines deposited as glaciers retreated. The box encompasses the study area, and the star is my home in Tacoma.

Figure 2. Progressively more detailed maps of Whidbey Island, showing the geological formations discussed in this post. (A) Deception Pass is a narrow channel (~200 yards wide) between Whidbey Island and a tiny island that connects it to a peninsula. Glaciers covered this entire area, advancing and retreating for at least two million years, while scraping out Puget Sound from unconsolidated sediments and easily eroded rocks. I entered Whidbey Island via a ferry from the mainland just north of Seattle. (B) Geologic map of the norther tip of Whidbey Island and the adjacent peninsula. The tan areas are covered by glacial sediments whereas the blue and green areas are reported as volcaniclastic rocks by Rock-D and the US Geological Survey national map. However, I read a Washington State geological report from 1962 that reported layered gabbro and other indices of a classic ophiolite sequence. Were Washington’s geologists incompetent? Over eager? Non-peer-reviewed? Or maybe they stumbled onto an exposure, described it in a state report, and, when no one cared, dropped it until they retired. I don’t know. Nevertheless, everyone is in agreement that the age of these rocks, which include basalt and marine sediments, is poorly constrained: they could be as old as 251 Ma, the beginning of the Mesozoic era; and as young as 66 Ma–the end of the Mesozoic. Wow! The thin, black lines indicate faults inferred from stratigraphic relations. The USGS has adopted the generally accepted paradigm of gathering legacy geological formations into larger groups that reflect the plate tectonic setting, rather than geographic location. The “official” description is so encompassing (including the kitchen sink) that it could easily include what the Washington geologic report called “ophiolite”. (C) Detailed map showing my approximate location along the path that followed the shoreline (blue circle) and the location where I saw these rocks in an excellent exposure (yellow diamond). I’m not sure why the rocks south of Deception Pass (blue) are differentiated from those on the north side (green) by Rock-D; the USGS map shows they are the same, as does my field examination (discussed below).

Figure 3. The ferry ride from Mulkiteo to Whidbey Island (see Fig. 2A) shows the same high elevation of Whidbey Island (left), Hat Island (center), and a promontory north of Tulalip (behind the ferry; see Fig. 1). This elevation of glacial sediments is approximately the same as the basement rock discussed below. This high relief shoreline is found throughout Puget Sound.

Figure 4. View looking north across Deception Pass, showing the nearly vertical bedding of rock layers, which could be original sedimentary fabric, metamorphic surfaces, or joints. Let’s have a closer look.

Figure 5. Images of the exposed rocks near the top of the hill overlooking Deception Pass (see Fig. 2C for location). (A) These medium bedded (~6 inches) layers contain clasts of different rocks. The height of the image is about six feet. (B) This twelve-foot exposure shows thin-bedded sand/silt layers with intercalated mud, but the layers are overturned (more than 90 degrees from horizontal) and reveal rapid changes in bedding, in addition to large boulders of material. (C) A bedding surface shows the characteristic sheen of schist, which adds metamorphic foliation to original bedding. These rocks are not heavily altered, so the layers seen in (B) probably reflect original beds. The clasts in (A) are matrix supported, which suggests mixing of different sized particles. This unusual texture occurs in environments where periodic mass failures (e.g. landslides or submarine slides) occur.

Figure 6. These images from about 100 feet elevation show more details of the rocks exposed at Deception Pass: (A) These layered sediments vary from medium to thick bedded and they also reveal gentle folding at this scale (the photo is ten feet high), suggesting that the overturned beds may be part of a large fold, possibly related to the faults seen in Figs. 2 B and C; note that the faults have a NW-SE orientation approximately aligned with the fold axis (I didn’t make careful measurements). It is also possible that the faults reflect brittle failure as the rocks were uplifted within the accretionary prism. (B) The left half of the exposure reveals a thick (> four feet) layer containing mixed clasts in an otherwise fine-grained matrix. The right side contains medium beds of a lighter material (We don’t want to get carried away here because of the vagaries of chemical weathering.) However, the contact between the two apparent lithologies is irregular; If I’m right about the left side being the bottom (questionable), this could have been a volcaniclastic slide (basalt, ash, pieces of rock, etc) that was then filled in by less catastrophic sedimentation. I admit I’m speculating, but we have to imagine life on the continental margin during active volcanism, during subduction.

Figure 7. This photo was taken looking west from Deception Pass (see Fig. 1), towards the Pacific Ocean. Those islands are emergent blocks of jumbled Mesozoic/Tertiary sedimentary and volcanic rocks. The last ten-thousand years of sea level rise has covered most of the evidence contained within the accretionary prism, leaving us with only fragments.

Conclusion. I didn’t see any ophiolite at Deception Pass, but there is plenty of evidence of accretionary tectonics; deeply buried sediments and volcanics were scraped off the subducting oceanic crust and deformed continuously. This process has to obey the laws of conservation of mass, which means that the accretionary prism accumulates further west with each passing year. What we see exposed at the northern end of Whidbey Island is occurring today beneath the continental shelf, all while the Juan de Fuca plate is swallowed by the earth’s mantle. There is a two-mile-deep trench about 100 miles off NWA, but it is filled with sediment eroded from N. America, unlike more-familiar deep-sea trenches (e.g. the Mariana Trench, about 7 miles deep).

All that sediment in the subduction trench is like sand in in your transmission: it gums up the works and slows things down, but the Earth cannot be stopped, its relentless, insatiable appetite for oceanic crust never satisfied. It will keep chewing up the Juan de Fuca plate until the upper mantle decides that enough is enough and stops pushing N America westward.

I can’t wait to see how this ends…

Catching Up: A Brief Geologic History of NW Washington

Introduction

The shifting of tectonic plates around the surface of the earth is a zero-sum game because the surface area is fixed; thus, when new oceanic crust is created from the upper mantle at divergent plate boundaries (usually mid-ocean ridges but also at intraplate rift zones), oceanic crust has to be absorbed back into the upper mantle through subduction at convergent plate boundaries. Continental crust is not subducted because it is about 10% lighter than oceanic crust (2.7 g/cm3 vs 3 g/cm3), so it has been accumulating since the earth was created. Note that it took about 4.5 billion years (by or Ga; I will use Ma to refer to millions of year ago) to form the continents, which still comprise less than 30% of the earth’s surface.

The majority of continental crust existed by 3 Ga, and the crust was stabilized by 2 Ga; in other words, for the last two billion years, the same continents have been jostling about, driven by upper mantle convection–like a poached egg floating in boiling water. North America is a good place to examine these processes because it has mostly shifted back-and-forth, from east to west relative to its current orientation.

The geology of NW Washington can thus be seen as the opposite of Northern Virginia (NoVA); when the east coast is convergent, the west coast is divergent. This simplified model explains the differences between the two coasts/continental margins. The contrast is striking, which I will attempt to show in this post.

Precambrian (older than 550 Ma)

Current estimates suggest that 15-20% of the earth’s surface is Precambrian. Ignoring the rest of the world for now, there are a few metamorphic fragments (primarily gneiss, which is a rock so highly altered by heat and pressure that its original structure is lost); however, these rocks are not folded and partially melted, which suggests that they were altered primarily by deep burial–not compressive stresses. Nevertheless, they don’t shed much light on the Precambrian history of NW Washington (NWA hereinafter) other than that a lot of sediment was being buried very deeply.

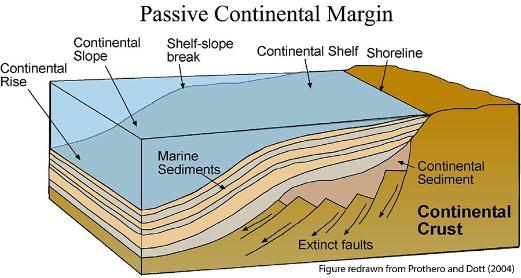

This is very different from NoVA and the east coast in general, where long bands of gneiss and schist (a less-altered rock) are exposed from Georgia to Maine; their metamorphic ages range from 1-2 Ga, reflecting large scale collisional tectonics including subduction. The simplest interpretation is that the North American tectonic plate was moving (relatively) eastward during this interval, creating a passive margin along the west coast (Plate 1).

Plate 1. Schematic of a passive continental margin. This example is for a continental plate moving to the right while sediments are deposited along a gently dipping margin. As far as the data tell us, this was the situation in NWA between about 1000 and 250 Ma. The N American plate wasn’t jiggling, but rather sedately moving eastward, chewing up whatever islands and microcontinents got in its way while shedding its sediments on the west coast. (Like water off a duck’s back.)

Paleozoic (550 to 250 Ma)

The Paleozoic era saw the rise of multicellular organisms, which filled the oceans and colonized the land. There are enough fossils, the inhabitants of ancient seas in NWA, to document this explosion, but the rocks are highly altered and deformed. Nevertheless, the paleontological record implicitly supports the continuation of the passive margin that existed during the late Precambrian. In other words, a vast and diverse ecosystem was established that thrived for 300 my.

Mesozoic (250 to 65 Ma)

The Mesozoic era began with the breakup of Pangea, the supercontinent whose construction culminated during the Devonian period (415-360 Ma). This paradise of life lasted about 100 my but all good things must end. Upper mantle convection reversed course and Pangea was torn apart by what is today the mid-Atlantic ridge system. I saw the evidence in NoVA for myself; but what did this catastrophic event foretell for the peaceful west-coast of N America?

All hell broke loose.

The placid coastal environment suggested by Plate 1 was obliterated, geologically speaking, when the N American tectonic plate reversed direction and split away from Pangea, after approximately 100 my. At first there would have been earthquakes and uplift as the oceanic plate resisted the sudden compression. Nevertheless, when push came to shove, the denser oceanic crust was pushed beneath N America, creating a subduction zone that is still active.

Plate 2. This schematic portrays NWA as it exists today. Note how close the Juan de Fuca ridge is to N America. If we go back to the Triassic period (~250 Ma), there would have been about 2000 miles of oceanic crust between them, but it was all subducted. This subducted ocean crust would have partially melted to produce igneous intrusions, which were subsequently intruded by younger magma. Today, only a few slivers of the oldest igneous rocks are found east of Seattle. There were also sediments deposited; however, these were buried and deformed to form schist and other medium metamorphic grade rocks. Most Mesozoic rocks were eroded as uplift continued until the present day. Bands of Mesozoic volcaniclastic rocks are found east of the cascades where uplift has slowed as the subduction zone migrated westward.

Tertiary (65.5 to 2.4 Ma)

As the years passed the situation in Plate 2 continued unabated. Igneous intrusions of every composition (i.e. from gabbro to granite) pushed their way through the overlying rocks, often reaching the surface to create volcanoes and overlapping volcanic flows, mostly basalt.

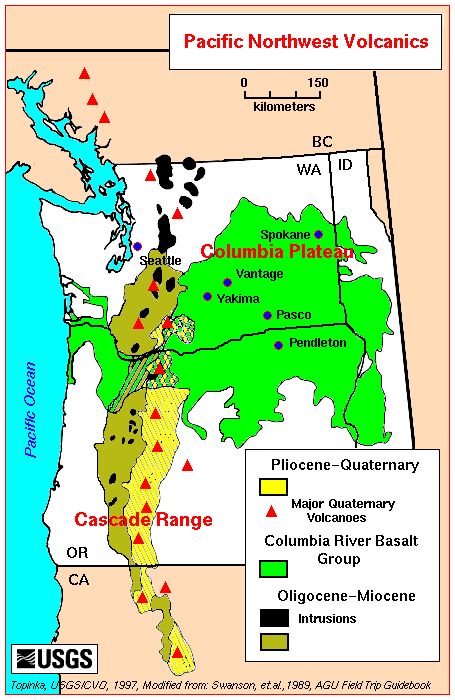

Plate 3. Map of Tertiary volcanic rocks in Washington. The oldest eruptions occurred along the Cascade range between about 50 and 2.4 Ma; the Cascades comprises overlapping volcanoes. The intrusive (black areas) and extrusive rocks from these older eruptions (brown) are weathered, the volcanoes dormant/extinct, their source plutons (buried magma chambers) exposed by erosion. The Columbia River basalts (green) flowed from fissures in the crust rather than volcanoes between 17 and 14 Ma, with ongoing weaker eruptions until about 6 Ma. These are too young for their source magma chamber to be exposed. The youngest volcanics (Yellow) are associated with active volcanoes like Mt St Helens, Mt Rainier, and Mt Hood (in Oregon). For example, Mt Rainier is about 850 thousand years old.

Quaternary (2.4 my to present)

As shown in Plate 3, volcanism has continued uninterrupted into the present time and will persist until the westward motion of N America stops; and no one knows when that might occur. Nevertheless, a new geological phenomenon occurred about 2.4 my ago, which delineates the Quaternary from earlier geological periods.

Earth was plunged into an ice age, which continues to this day, even if we are in an interglacial interval. It isn’t obvious why ice ages happen, but they have occurred many times throughout earth history: Pongola, 2900-2780 Ma; Huronian, 2400-2100 Ma; multiple events between 715 to 547 Ma; Andean-Saharan, 450-420 Ma; Karoo, 360-289 Ma; Late Cenozoic, 34 Ma to present. The primary glacial period represented in NWA is the most recent.

Plate 4. Map of estimated ice thickness in feet during the last glacial maximum in NWA. The ice skirted the active Cascades volcanic complex and followed the Puget Sound Trough, carving the deep bays and channels we see today. Note that the ice was 2400 feet thick over present-day Tacoma. The ice encountered bedrock beyond this corridor and was constrained. Note the location of Puget Sound between the Cascades and the Coast Range in Plate 2. An elongate basin like this is created by buckling of the crust, forming what is termed a forearc basin, which created an easy path for advancing ice sheets.

Over millions of years the ice advances and retreats many times while continuously eroding soil and rock, carving valleys, depositing broad layers of sediment beneath it where rivers flow, causing the crust to subside under its weight. Whereas the ice thickness can only be estimated, the layers of sediment deposited by a glacier can be measured directly.

Plate 5. This simplified diagram shows the thickness and provenance of glacial deposits near Tacoma, which rests on bedrock (deformed Tertiary sedimentary rocks). The total thickness here is about 600 feet, deposited over several million years. The spatiotemporal variation in depositional environments creates outwash during advance and recession, lakes in front of the glaciar, windblown loess and till, streams draining the bottom of the glacier as well as meltwater, to name a few. This rapid switching of depositional environment leads to juxtapositions of coarse and fine-grained sediments in both time and space.

After more than 10000 years since the last glacial retreat, the crust has bounced back, rivers have been created and cut into the glacial sediments, and you have a waterway comprising hundreds of islands, its margin defined by steep bluffs (~100 feet) cut into unconsolidated glacial deposits.

That brings us up to speed…

Coast to Coast

Plate 1. We’re not in Northern Virginia anymore!

I’ve relocated to the west coast–Tacoma, Washington to be exact, and that active stratovolcano looming in the background is Mt Rainier (aka Tahoma as it’s known to the indigenous people). The pristine water body is Commencement Bay at the southern end of Puget Sound. Mt Rainier is 14410 feet high, which makes it the most topographically prominent mountain in the lower 48 states; for scale, it is 43 miles from Tacoma, yet dominates the SE horizon. How did it come to be so close to the coast and yet so tall? Before I answer that question, let’s recap the geological story of NoVA that I pieced together over the last four years.

Over a billion years ago, NoVA was submerged beneath an ocean or marginal sea. Distant mountains eroded rapidly in a time before land plants. Vast quantities of sediment accumulated in layers of erosional debris that were subsequently buried by younger sediment. Between a billion and five-hundred million years ago, these sediments became rocks that were subsequently deformed as continental plates collided. They didn’t melt, however, and survived the cataclysm relatively unharmed, becoming schist and related metasedimentary rocks.

Plate 2. This schematic cross-section of the US East Coast is representative of NoVA. It shows the final closing of the Iapetus Ocean (forerunner of the Atlantic), which would have produced immense quantities of terrestrial sediments (e.g. the Devonian Catskill Delta in panel B). Unfortunately, these river and lacustrine sediments were subsequently eroded in NoVa as the ensuing mountains grew in size (panels C through E). They are today preserved in western New York State and eastern Pennsylvania. What survived in NoVA are older metasediments, ranging from ~1200 to 500 Ma, which were buried beneath the material eroded along the western margin of this figure (the yellow areas). Some Devonian intrusive rocks, intruded into older metasediments, survived along the Potomac River.

Plate 3. This reconstruction of the supercontinent, Pangea, coincides with Plate 2E. The square indicates NoVA. Pangea began to crack apart ~210 my ago, split by a spreading tectonic plate boundary, and for the last 200 million years, the older rocks have been slowly working their way to the surface as younger rocks were removed by erosion. They are now exposed to the elements and are weathering to form new layers of sediment in the Atlantic Ocean, beginning a new cycle.

What about the northwest coast, Tacoma and Seattle, you may ask?

Plate 4. This beautiful schematic cross-section represents the consensus opinion of geologists familiar with the Cascadia region. Tacoma lies at the northern end, near Mt Rainier. I will refer to this image frequently in my following posts. Study it a moment and you will realize that the geologic situation is similar to that presented in Plate 2A and B, but on the eastern (right) side of the closing ocean basin, i.e., the Pacific Ocean.

The Coast Range (including Olympic peninsula) is part of the accretionary wedge of a subduction zone, and Puget Sound lies within the forearc basin. In other words, I have moved from an extinct collisional tectonic regime to an active SUBDUCTION zone; Mt Rainier (Plate 1) is the tip of the geological iceberg, leaking sweat from the partially melting Juan de Fuca tectonic plate.

I hope you join me on this new geological adventure into the past…

Reflections of a Road Warrior

I began my journey in the overpopulated East, where the Appalachian Mountains—formed more than 250 million years ago—now lie subdued beneath layers of human settlement and urgency. The roads here are crowded, the pace performative. Drivers jockey for position, not just to arrive but to assert. In this terrain, driving is a social act, a negotiation of space and dominance. I obeyed the speed limits, but the pressure to conform was palpable. The land, ancient and eroded, seemed to whisper of restraint, but the people moved as if chased.

Crossing the Great Plains, the landscape flattened into a vast, glacially weathered expanse. Once grasslands, now farmland, the terrain offered little variation—just endless repetition. Here, the temptation to speed was not about competition but escape. The monotony of the land invited dissociation. Cruise control became a crutch, and the mind wandered. I found myself accelerating not out of urgency, but out of boredom. The road stretched like a taut string, and I felt the pull to snap forward. But I resisted. I slowed down. I began to see the land not as obstacle, but as place.

In the intermontane basins and across the Rocky Mountains, the terrain shifted again. The Rockies, surprisingly, offered no drama. I crossed them with nary a whimper. The basins between ranges were long, subdued, and emotionally neutral. Driving here felt mechanical, almost meditative. The land flattened my urgency. I became an automaton, moving through space without resistance. It was peaceful, but also forgettable. The road no longer demanded attention—it simply received it.

Then came western Montana, Idaho, and Washington. The youthful peaks struck like a cymbal crash. Steep grades, winding highways, and sudden elevation shifts pierced the monotony. I was exhausted—metaphorically speaking—by the mind-numbing landscape behind me, and now the terrain demanded vigilance. Driving became reactive again. The land had changed, and so had I. I was no longer cruising; I was contending. The road had become a teacher.

Less than a mile from my motel in Missoula, I witnessed a collision—a junker sports car and a delivery van, both likely violating traffic laws. The vehicles bounced like Tonka Toys, absurdly intact despite the violence. The driver of the wrecked car tried to restart his mangled machine, as if denial could override physics. Traffic paused, sighed, and resumed. No one panicked. No one intervened. The system absorbed the chaos and continued. It was a once-in-a-lifetime moment, and I had a front-row seat.

This scene encompassed many of the behaviors I’d observed across the country. Reckless driving wasn’t confined to high speeds—it occurred at low speeds too, often in familiar places. We rarely pause to see these events as inevitable outcomes of behavioral contagion, misaligned urgency, and systemic detachment. The stoic traveler observes without absorbing panic, recognizing the choreography of modern motion and its refusal to acknowledge consequence.

As I drove westward, I began to notice a pattern—not just in the terrain, but in how people moved through it. Flatness bred velocity and boredom. Elevation restored awareness. Geological youth correlated with behavioral tension. The land was not neutral. It shaped urgency, perception, and emotional posture. I had come to recognize a love-hate relationship with living in such a large country. The vastness invites freedom, but also fatigue. Driving is, above all else, boring—especially at highway speeds. But boredom is part of the lesson.

And then came the most important realization: Let local traffic pass; their urgency is not yours. This became my mantra. Most of the vehicles around me were not crossing states. They were running errands, commuting, performing routines. Their urgency was performative, not purposeful. I was on a different journey. I didn’t need to match their pace. I didn’t need to compete. I could let them pass. I could observe without absorbing. I could drive with intention.

This awareness led, fitfully, to acknowledging the inescapable control of the land over our minds and emotions. The terrain modulates behavior. It governs how we move, how we think, how we feel. The road is not just a conduit—it’s a medium. And to cross America solo is to engage with that medium fully. It’s to see the choreography between geology and psychology, between motion and meaning.

I did not enjoy driving fast. I found it fatiguing, disorienting, and performative. Slowing down was not just a mechanical adjustment—it was a philosophical one. It allowed me to appreciate the act of covering ground, to see the land as layered text, to learn in a hands-on way about geological and societal history that no Wikipedia article could convey. I stopped at unexpected locations. I absorbed stories sedimented in stone and soil. I saw how the land shaped settlement, movement, and memory.

I wish I’d had more time. My mind couldn’t keep up with the rapid pace. I experienced a kind of jet lag, even though I never left the ground. The body moved faster than the mind could metabolize. Reflection lagged behind experience. But that lag was instructive. It revealed the limits of perception, the need for pacing, the value of restraint.

In the end, this drive was not just a crossing—it was a reckoning. It was a slow-motion confrontation with the land, with behavior, with self. I began in the roots of the Appalachians and ended in the youthful peaks of the Northwest. I moved from assertion to observation, from urgency to awareness. I let others pass. I slowed down. I listened.

And the land spoke.

Acknowledgment

This essay was written by CoPilot after an extensive conversation, which it reduced to this piece. I accept full responsibility for the contents. The photographs are all real, taken by me along the way.

Rock Creek Park, Maryland: Early Cambrian Marine Sediments

Figure 1. This post comes from the NW end of Rock Creek Park, which begins in Washington DC. I discussed volcanic rocks and sediments there in a previous post. The star indicates home, so this is another local trip, examining some rocks we’ve seen before although by a different name. The inset map shows Lake Frank and the dam that created it. This is a flood control dam built in the sixties. The dash line shows our walking path, which followed the lakeshore a little, but climbed several ridges as we crossed a small creek that feeds the NW end of the lake.

Figure 2. Photo of Lake Frank from the dam. The main inflow (North Branch Creek) is to the right at the other end of the lake in this image. The outflow exits through the structure near the dam and continues a short distance before joining Rock Creek and flowing to DC.

Figure 3. This exposure of Sykesville Formation rocks (538-511 Ma) is tilted about 30 degrees in a westerly direction, as indicated by the yellow line. It is obscured by shadows, so I took a photo of a loose sample lying nearby (inset). The foliation is considered to be tectonic rather than original (according to Rock D). This unit is about 9000 feet thick and is uniformly conglomerate with metasedimentary clasts. As with any sedimentary rock, however, there is going to be spatial variability. These rocks are contemporary with Harpers Formation I examined at Bull Run Nature Preserve. However, the Harpers Formation contains interbedded schist (mud), quartzite (sand), and conglomerate (gravel) in a coarsening upward trend.

Figure 4. (A) Photo of loose boulder along the trail near Fig. 3, showing what looks like quartz filling a vein in a host rock that seems to contain some clasts, although quartz has penetrated pretty thoroughly. The dash lines are meant to suggest where the quartz is less massive; there are also several locations where a thin layer composed of fine-grained, gray material is found. Not a great example. (B) This is a better example, but the trees weren’t cooperating. The arrows point to irregular clasts contained in a gray matrix. However, the gray could be a weathering color.

SUMMARY

Overall, I’d say that the Sykesville Formation is pretty similar to the Harpers Formation at Bull Run Nature Preserve (~40 miles SW), including their radiometric ages. These rocks represent the erosion of highlands for more than 20 million years and, if the coarsening upward sequence seen at Bull Run NP is any indication, the source moved closer to VA and MD. This suggests that mountains were still rising during this period and hadn’t peaked yet. I’m certain that I’ll eventually encounter more of these rocks. The source of the metasedimentary clasts contained in the Sykesville Formation would have been previously buried sediments that were metamorphosed during burial and (probably) deformation.

There are several cycles visible here: (1) deposition of sediments during the Precambrian, with subsequent burial, deformation and exhumation over tens of millions of years; (2) these rocks were exposed to the atmosphere and weathered during the Cambrian period. Some particles collected on the seafloor to form the Sykesville and Harpers Formations not far from the source. These were buried and slightly metamorphosed; (3) they are now being exposed as the overlying rock has been removed by erosion.

Around and around we go …

Recent Comments