From There to Here: Wyoming

We discussed the tumultuous history of Precambrian rocks in Montana in my last post. The story of crustal shortening in western North America continues to this day. The huge, shield volcanoes comprising the Cascades Mountains show that this westward motion has not ceased at the current time.

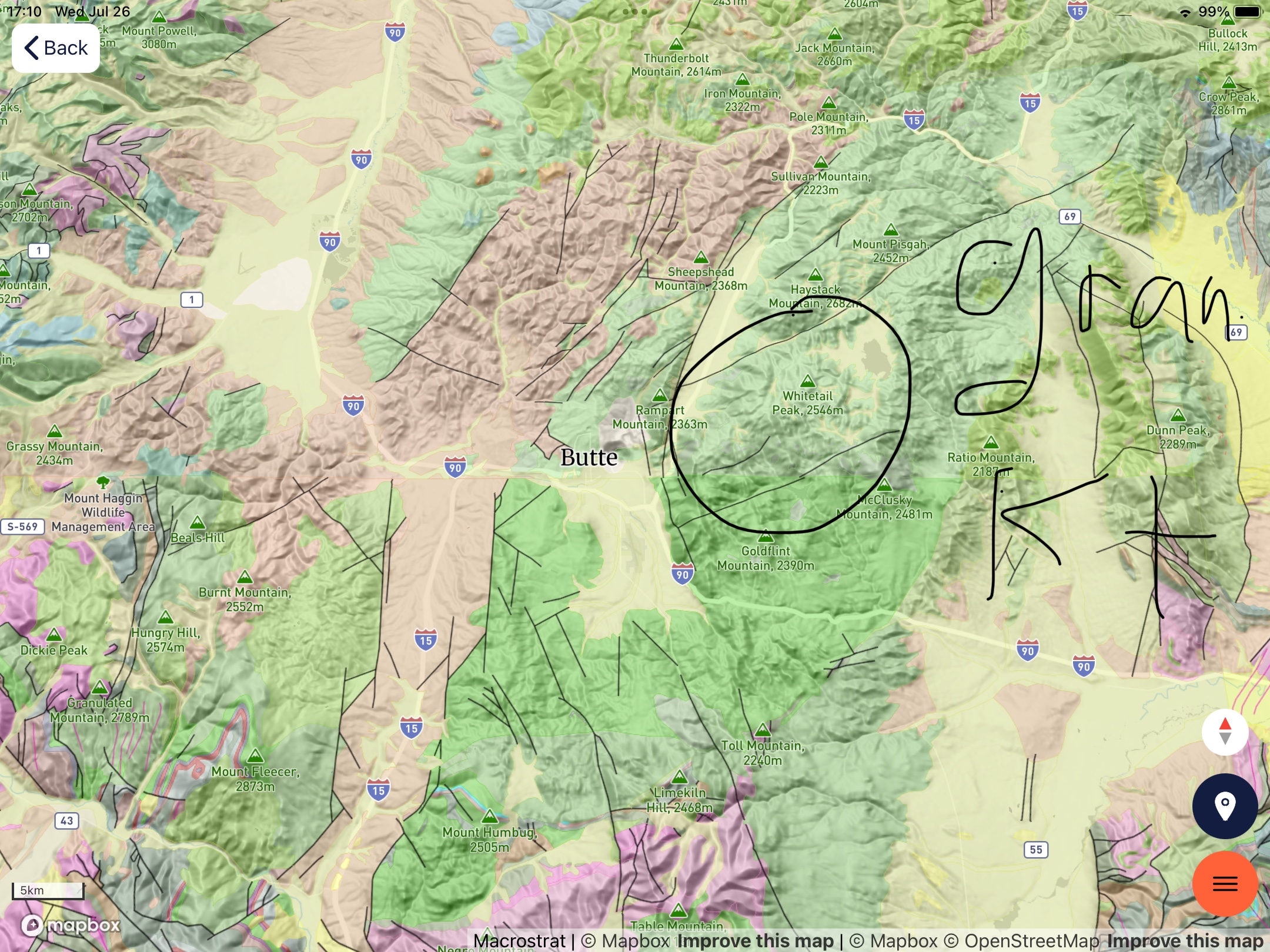

The story of oceanic subduction and collision with multiple microcontinents is recorded in the rocks I had to drive past, so I have to resort to a geological map again.

Summary. This was a short post because I was occupied and didn’t have time to explore this fascinating region. Nevertheless, I can confidently say that when Pangea broke up, the North American tectonic plate began to “swallow” the proto-Pacific plate and any microcontinents it harbored.

This 200 my long process created the Rocky Mountains, the overthrust belts of Montana, the Black Hills of South Dakota, the Colorado Plateau, the volcanic Cascade Mountains, the complex system of faults that define California, and so many other geological features of the western North American craton.

It wasn’t as if another gigantic mountain range could form in the aftermath of Pangea’s break-up. The earth can only produce one of them every couple hundred million years, a tectonic pattern called a Wilson Cycle.

Spokane, Washington, to Gillette, Wyoming: Geology in the Rearview Mirror

This post is experimental and not particularly interesting, but it is the best I can do under the circumstances; I followed Interstate 90 through the Rocky Mountains at 70 mph, with no pull-offs, and trying to take photos in the heavy traffic would have been suicidal. Instead of including a map, photos of outcrops, and some close-ups to examine mineralogy, I am relying on geological maps and my memory. The most experimental part is that I’m working on an iPad, which is a blessing and a curse. Let’s see how it worked out.

Summary. The oldest rocks (Precambrian metasediments shown in purple shades) are scattered throughout the Rocky Mountains. These old rocks were pushed and pulled for hundreds of millions of years as microcontinents collided to form what we call western North America.

Paleozoic rocks (500-230 my) that would have been deposited on top of them, or intruded into them, are only found in scraps here and there (I’m speculating, but Paleozoic rocks have a habit of turning up in the unlikeliest places).

During the late Cretaceous (about 80 my), granitoid intrusions forced their way into these older rocks, as I saw at Butte and other small mountain ranges (pink and tan hues). This was a geologically active period in the evolution of western North America.

About fifty-million years ago, volcanoes formed along the western margin of North America (e.g. Mt Hood and other volcanoes produced thousands of feet of volcanic rock, forming the Columbia plateau (yellow shades in Fig. 5). At approximately the same time (50 – 5 my) sediment was collecting in lakes and shallow inland seas leftover from the Cretaceous Interior Seaway. These sediments are undeformed and not very well lithified (i.e. not buried deeply); they appear east of Bozeman MT as green in Fig. 5.

Hidden beneath the Precambrian rocks, which were pushed eastward as much as 150 miles in Canada, and Miocene sediments, lay the oil and coal rich Cretaceous sediments laid down between about 150 and 60 my ago. As proof of this, Billings MT (rightmost circled area in Fig. 2), with a population less than 150 thousand, has three oil refineries; but it is so remote, with so little infrastructure (e.g. pipelines), that trucks deliver refined petroleum products to rail cars. It is a modern western boom town.

We’ll see what tomorrow brings …

A question of scale: Indian Canyon Falls

Summary. I found Indian Canyon falls by looking for Lake Missoula park, which turned out to be closed to the public. However, the Park Service supplied a link to other geological attractions, with navigation instructions—GoogleMap took me to a nondescript, heavily wooded area, where I found something I hadn’t expected to see.

The rivulet of water flowing over the “fall” during the dry season is an omen of what is to come for this relatively unknown canyon (it was actually covered with biking and hiking trails). At first the trickle carries only mud, then sand, then gravel, then boulders, then …

Indian Canyon falls is how it begins. Where it ends …

Think big …

Bowl and Pitcher: Volcanic Rocks at Riverside Park, Spokane, WA

Summary. Today’s excursion brings two questions to mind: 1) What is the meaning of such an immense thickness (hundreds of feet) of basalt with such an unusual form? (I’m going to call it “oyster” lava.); 2) How did rocks that are nowhere to be seen in the area (refer to Fig. 3) end up in Riverside Park?

Basalt flows are known to be highly irregular in outcrop because lava flows in tendrils, sheets, molten chunks blown out of a fissure; however, these flows (and there must be thousands of them exposed in the cliffs along Spokane River) are eerily uniform and individual flows can’t be identified. This is unusual for relatively young volcanic rocks. The problem is exacerbated by the scarcity of soil profiles; there wasn’t time for water to react with the highly reactive minerals in basalt before another layer was deposited. I don’t have an answer.

The second question is easier to answer. During the last two million years, this region was covered by thick ice sheets that periodically melted and then expanded. Dams of ice formed huge lakes like Lake Missoula, the size of some states. There is overwhelming evidence for the catastrophic collapse of such an ice dam between 20 and 10 thousand years ago. The region surrounding Spokane contains many igneous, sedimentary, and metamorphic rocks dating from Precambrian (older than 500 my) to the age of these basalts (about 10 my).

The resistant cliffs surrounding the “bowl and pitcher” channeled such massive floods many times, beating very hard rock (e.g. Fig. 8) to a pulp as the boulders bounced along and hit other equally hard rocks.

I don’t like unanswered questions but that’s how it goes because the rocks keep secrets …

Volcaniclastic Deposits at Motel 6

This post is a little weak but I wanted to show that we can find evidence of the earth’s history in our back yard (literally). My interpretation may be completely wrong but it is consistent with my observations and (limited) understanding of volcaniclastic deposits.

I’m going to look at some more curious volcaniclastic deposits tomorrow …

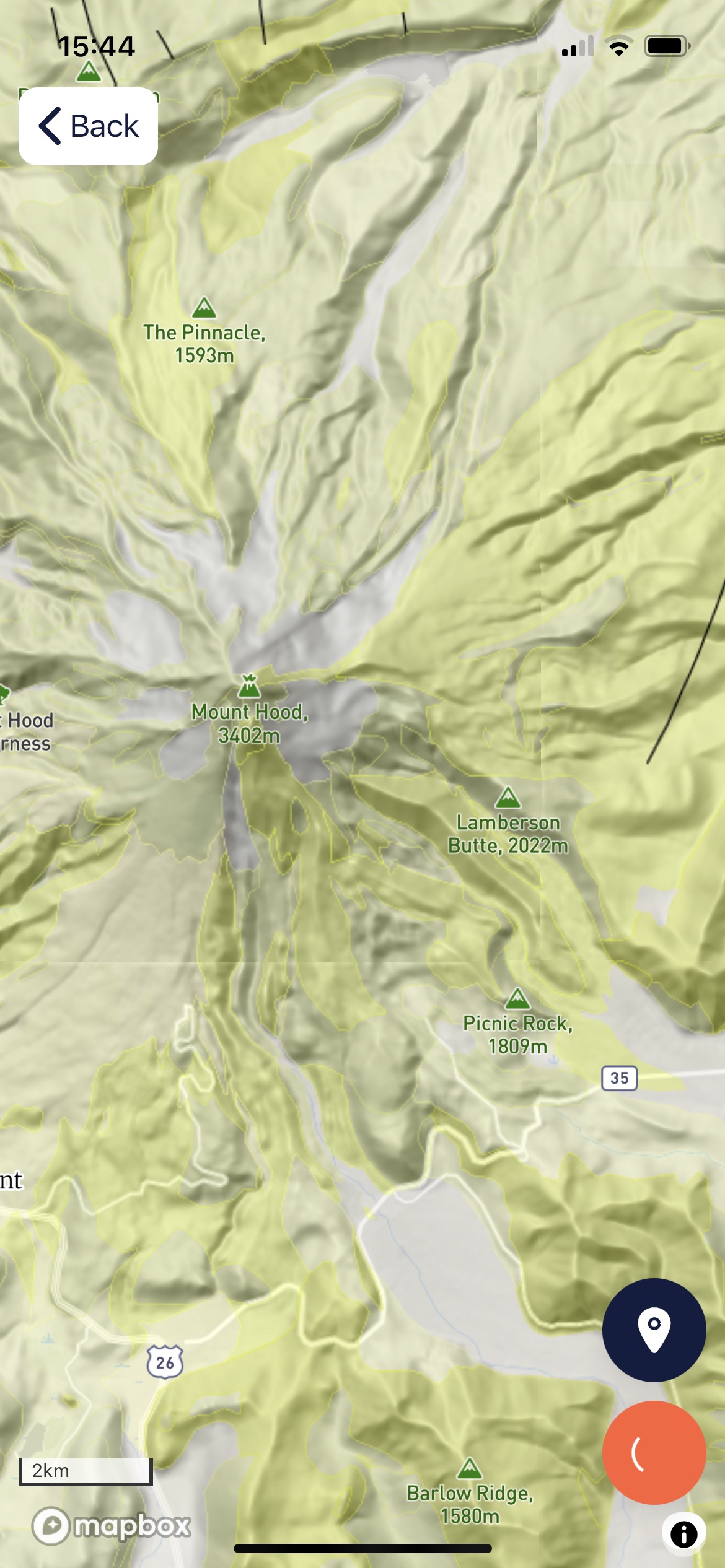

Mount Hood: Volcaniclastic Deposits

Summary. Understanding volcanic stratigraphy is easy with a simple exercise. Spread your left hand out on the table, fingers apart. Each finger is a volcaniclastic flow, either pyroclastic, lava, or a lahar, separated by hundreds of thousands of years. Now, lay your right hand over the left but not with the fingers aligned. Imagine doing this hundreds of times, while peeling away the tops of your fingers randomly (i.e. erosion).

Remember the violent eruption of Mt. St. Helens? It was a pyroclastic eruption (mostly red-hot ash) but what made it destructive was the boiling hot mud encasing boulders of older volcanic material. The blast flattened the trees for miles and the lahar cleaned up the debris.

Imagine such an eruption occurring every year … thank god they are separated by centuries or millennia.

There’s only so much energy available, even for the dynamic earth …

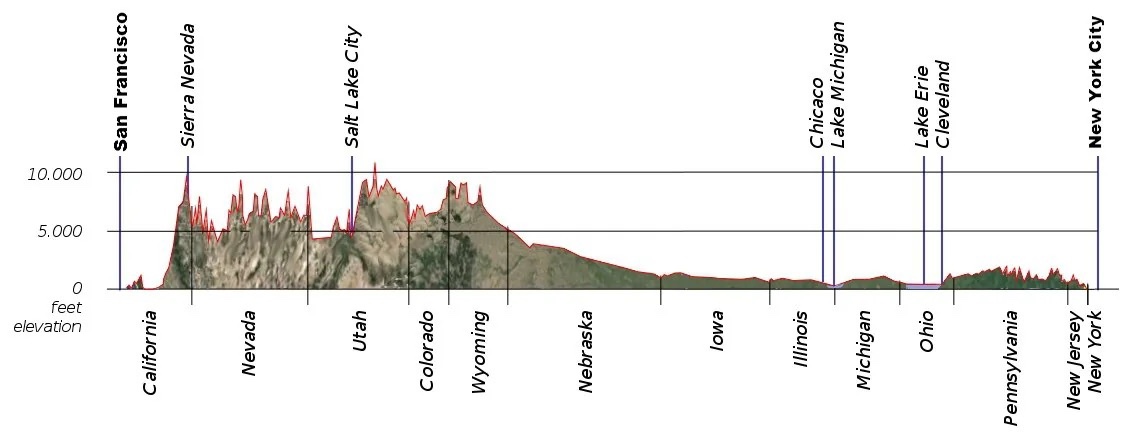

Road Trip Across the U.S.A.

This post is being written in Portland, Oregon, 2800 miles from Northern Virginia, where this journey began. I’m working on an iPad, which is new to me, so I’m going to limit this to a summary of previous posts, and briefly discuss some rocks I haven’t discussed before. I’ll go into more detail on the return trip, which will, however, take a different path.

I have said a lot about the rocks in NOVA (Northern Virginia), so I’ll refer to those posts. The eastern end of Fig. 1 is underlain by rocks more than one billion years old that record a collision on a continental scale.

We also found evidence of deposition in marine and coastal settings throughout the Paleozoic (~500 to 250 my), which I’ve discussed before. This period of erosion was interrupted in the Triassic Period, about 200 my ago, when the east coast began to stretch; coarse sediments filled newly developing basins throughout NOVA.

Our westward journey took us through Maryland and Pennsylvania (see profile above), where we found evidence of broad, shallow seas to the west and rising highlands to the east throughout the Paleozoic.

West of the ancestral Appalachian mountains, from Ohio to Illinois, we saw rolling hills covered with farms that replaced primordial forests. I don’t have any photos of this area, but there isn’t much to see. However, this is where extensive glaciation becomes evident, continuing across the Great Plains to Nebraska. I wrote about the moraines that dominate this region in a previous post.

This post picks up the story in eastern Wyoming (see profile above), where we find sediments deposited in coastal areas during the Late Cretaceous (~100 my) dominating the region.

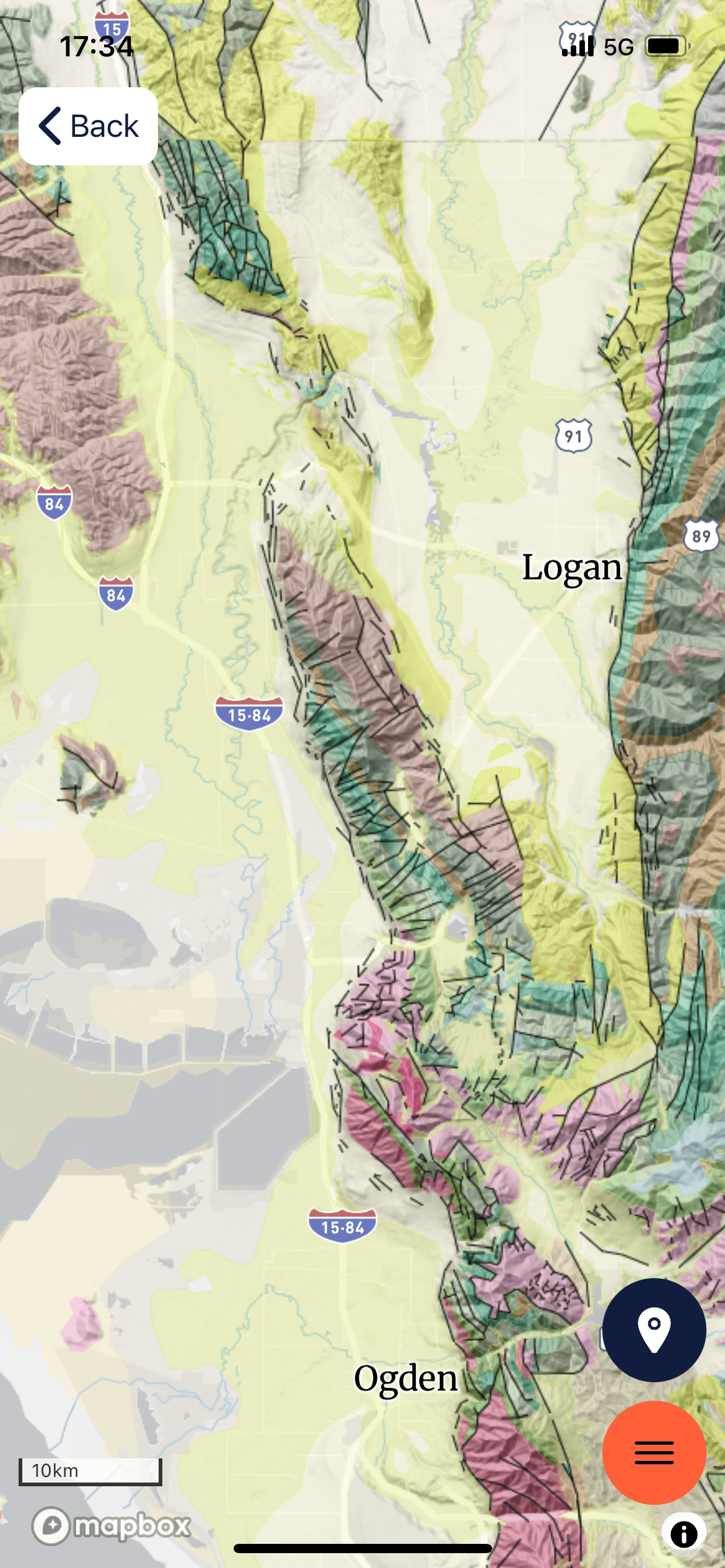

Figure 2. Geologic map of the area around Rawlins, Wyoming. The majority of the rocks (green hues) are Cretaceous (~145-65 my). Faults (black lines) separate these older nearshore sands and muds from Miocene (~20 my) coarse sediments (yellow colors), Paleozoic marine sediments (aqua tints), and Mesozoic nearshore sediments (blue hues). Note the arch form of the Mesozoic layers; this is an anticline, folded layers of rock, the result of crustal shortening (i.e. compression).

SUMMARY. We started out in NOVA, where a titanic collision occurred more than 500 million years ago. We saw evidence of a similar orogeny in the Precambrian rocks exposed in Utah, Wyoming, and Idaho, long before they were deformed and pushed eastward.

During the Paleozoic era (500 – 230 my), thick layers of sediments were deposited in Pennsylvania (see Fig. 1) as the ancestral Appalachian Mountains rose, then eroded over hundreds of millions of years. The proto-Atlantic Ocean (Iapetus) opened and closed during this immense span of time.

We saw similar Paleozoic sedimentary rocks in Utah and Idaho (no photos available) but the big picture of continuous deposition along huge swaths of what is today western North America is recorded elsewhere (e.g. the Grand Canyon and Colorado Plateau).

The Mesozoic era is mostly recorded in sediments associated with the break-up of Pangea in NOVA, where stretching of the crust produced ridges and intervening grabens filled with coarse sediment. The Mesozoic and Cenozoic eras were spent eroding the ancestral Appalachian mountains as Eurasia and North America went their separate ways.

Vast expanses of shallow marine and lacustrine sediments were deposited in the (modern) central and western United States during the Mesozoic, accompanied by the eastward push of older rocks by episodic collisions; this was not a continental collision but probably a series of micro continents and island arcs being absorbed as oceanic crust was subducted. A vast interior seaway reached from the Gulf of Mexico to the Arctic Circle at this time.

The Cenozoic saw the eruption of vast quantities of volcanic material in Oregon and Idaho as Mt. Hood (and other volcanic centers) reached its peak of activity. The Cretaceous seaway dried up and terrestrial sediments replaced marine deposits, as the Colorado Plateau rose more than 5000 feet, shedding sediments everywhere. Finally, great ice sheets carved the earth’s surface into a new landscape defined by moraines and glacial valleys.

The Cenozoic is mostly under represented in NOVA because sediment collected on the continental shelf of North America, which was (and still is) a passive margin. Everything that was carried westward by the Mississippi River system was deposited ultimately in the Gulf of Mexico, where huge oil and gas fields developed from organic material transported by an ancestral Mississippi River drainage system. There was no room for sediment as the Appalachian mountains rose, in response to the removal of miles of overlying rock.

This has been a brief and probably inaccurate comparison and contrast of eastern and western geology of the United States, but it is only what I’ve seen with my own eyes, enhanced by the vast knowledge accumulated by generations of geologists tying the story together.

We’ll see what I learn on the return journey …

Recent Comments