The Lemay Auto Collection

The museum occupies the entire grounds of a 20th century boys school, so they have a lot of cars!

Trinity House

Trinity House was written during the Covid pandemic and thus expresses my frustration with the divisions I was watching grow within American society. I didn’t want to write a dramatic story but that’s probably what it is. As the author I accept full responsibility for this dark comedy that attempts to explore the relationship between superstition and innate human behavior.

The professionally done cover encapsulates what is wrong with extreme religious beliefs. One side of the church’s lawn is well kept while the other is overgrown with weeds, the tree dying, yet the gardener is waving as if there were nothing wrong, oblivious of the damage he has done by his own acts. But he isn’t happy, far from it; his demons are haunting him.

I tried to capture the complex social environment of deeply conservative Christians torn between their dogma and the reality of life, the neighbors they are equally capable of loving or hating. I personally love the ending, but then I’m an agnostic, maybe an atheist. At any rate, it felt good to get yet another burden off my chest.

Publications: Deep Dives into Science Fiction

I’m not reposting these book descriptions in chronological order. They were originally written as my interest changed through time and in response to the news. This post focuses on four science fiction novels inspired by the news, and my visceral reaction to the simplified reality portrayed in pop culture. Thus, my attention turned to early reports of Artificial Intelligence, as Large Language Models were presented to the public. All the hype about deep-learning algorithms becoming intelligent after being trained on vast amounts of publicly available books, movies, images, etc. bothered me because, if the objective (intentional or not) is Artificial General Intelligence, these programs all missed the boat. For example, a human brain isn’t fed a stream of data to become the cognitive wonder we claim to be; it spends years processing and assimilating sensory data–touch, hearing, smell, sight, taste. So I imagined what might be occurring in a private lab somewhere, an event so profound it would change the course of civilization. It remains entirely possible that a scenario like that portrayed in Aida is actually playing out below the radar of mainstream media attention.

AIDA is an acronym for Artificial Intelligence Daughter Algorithm. It is the story of a heartbroken computer scientist who decides to create a daughter to replace the one he lost, along with his wife, during childbirth. But his creation exceeds his wildest expectations. The simple cover encapsulates the central theme of the book. Look at the picture closely and you will find that the beautiful woman depicted in the left side of the face is matched by an evil countenance on the right. There is no purpose in issuing warnings about unintended consequences because humans never look beyond the immediate horizon.

Writing Aida got me to thinking about AI and robotics so, naturally, I wrote another book on the subject. I wondered what would happen if an AGI hooked up with an advanced humanoid robot. One possibility is encapsulated in the title of this novel: it would be a Black Dawn for humanity if the wrong people got their hands on it. I wanted to call this book, AMANDA, the name of the central character. As you might have guessed that is an acronym–AMANDA is an Autonomous Mobile Anthropomorphic Neural-synthetic Deep-learning Architecture that has spent 16 years being raised as the daughter of a couple of computer scientists.

The naive Amanda needs a guide for her intellectual and emotional journey when her family is murdered and her body stolen. To add an interesting twist to the tale, I reintroduced the elderly writer from A Change of Pace as the author of the novel that influenced her parents: Aida not only impacted AMANDA’s creators, it also leads to its author (Jim Walsh) being pursued by the bad guys. Naturally, Amanda and Jim become unlikely partners in a quest of personal importance to both of them.

This is an adventure that doesn’t slow down until the end.

Apparently, I needed more adventure after writing Black Dawn, so I wrote a what-if novel about what might happen if the basic laws of physics, or the constants we take for granted, were to change. The result is Broken Symmetry, a story about a graduate student who finds herself the locus of a bizarre chain of correlated events–personal, social, and even geological–with no obvious causation.

The action in this story is too cataclysmic to keep under wraps, not when the San Andreas fault ruptures and Yellowstone caldera explodes, but that’s only the geological story. People begin to change and someone wants to stop the contagion. (Don’t they always?)

The Edge of Space was my response to a news story about Voyager One having communications problems after exiting the solar system. The story is told through the eyes of several characters with different perspectives. Their interactions are rife with speculation about what is occurring, from a young woman from Thailand to the president of the United States. As the story unfolds, these characters move in and out of each other’s lives.

I have written an outline for a sequel to this story of First Contact…

Publications: A Change of Pace

As much as I enjoyed writing the Unveiled books, I was ready for a change and, besides, I had some more issues to work through. I’m not generally a conspiracy fan but 9/11 got everyone’s attention, especially with that whitewash report the federal government produced. However, in Night Shift, I got distracted from the conspiracy theory and really dug into a tragic relationship between two people who couldn’t have been more different.

This book was a lot of fun to write, even though part of the story was tragic. I felt as if I knew Faheem and Sofia personally by the end. What a crazy couple, but they stuck it out despite their differences and what was happening to them, most of it their own fault. I’m still not certain if Faheem stumbled onto the truth…

I did a lot of reading about psychology and behavioral disorders while writing Night Shift; so, naturally, I was inspired to write about myself, not in an autobiographical style but more as a novel with a central character who could be me. Thus, A Change of Pace was created to write about myself anonymously. There’s a little biography in there but not much; nevertheless, Jim Walsh is as close to me as I can imagine a character. I also noted some eery similarities to my life that were not intentional. Perhaps writing a pseudo-autobiography was therapeutic after all.

The cover sets the stage for this light romantic comedy about a fish out of water. Besides jumping from action/adventure to romantic comedy, I also did the cover artwork myself. I had used the same studio for the previous four books but this one seemed too simple for their expertise (they specialized in hand-painted fantasy art). Thus, the cover features the motorhome I was living in at the time and my old Land Cruiser, but I never lived in an upscale apartment in my life. That part is fantasy.

I love writing novels because it’s like binge watching several seasons of a favorite show and getting to know the characters intimately. There is so much that can’t be squeezed into the final text. Still, it can be fun to explore a stranger’s life for a few days, a span of time too brief to really get to know them, yet long enough to reveal something significant about their lives.

I took a break from writing novels to write a series of short stories that shared a common theme, which developed while working on them. I collected them together into Class of 1974. Imagine the different lives of people who graduated high school the same year, but had nothing else in common; until they all won the lottery.

These stories share two common themes: the title implies that the stories are tied to a rather dismal year in recent American history; the second commonality is more dependent on luck. I created the cover from a stylized Escher staircase showing people going nowhere, which seems appropriate for my cohort.

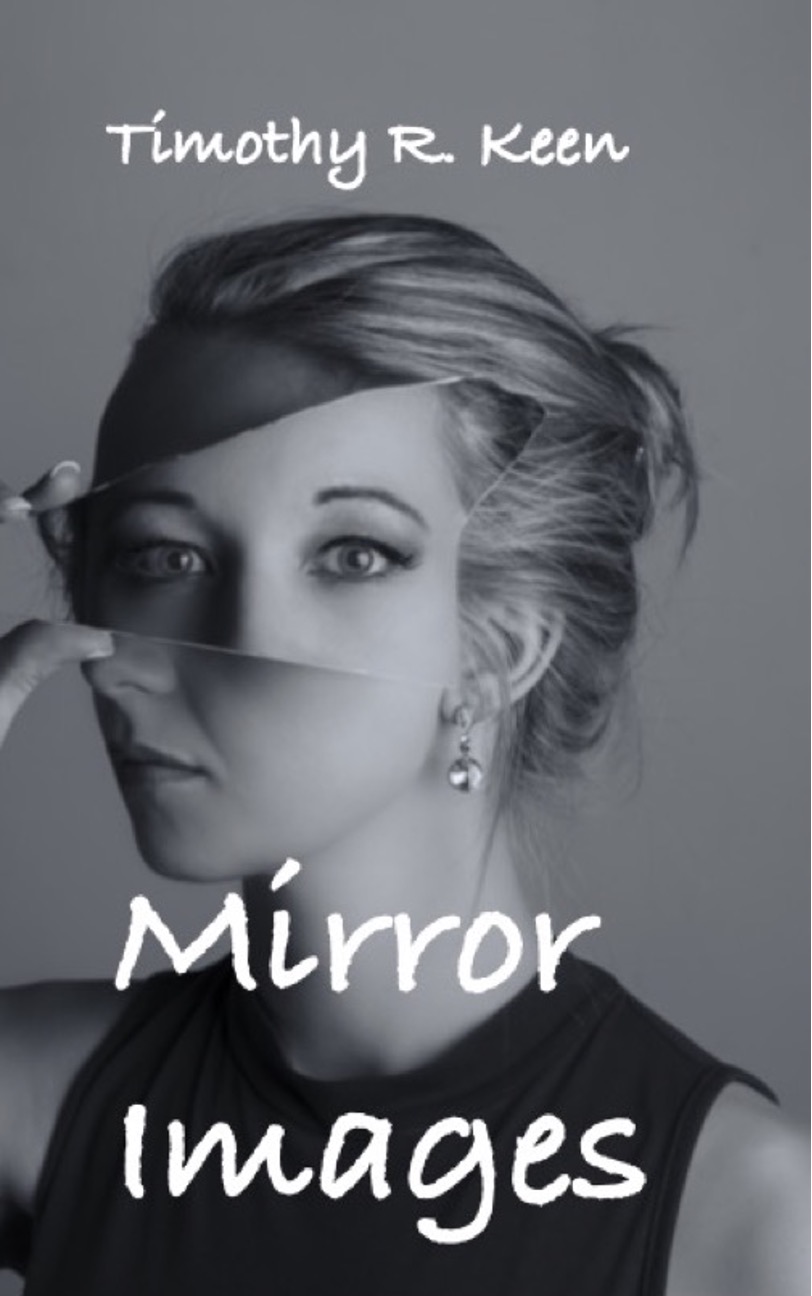

I think every writer should write short stories between major works. It’s like writing practice. And short stories are a great break from the concentration necessary to complete a novel, not to mention the lengthy timeline. I think the idea for Mirror Images originated in a dream (I can’t remember for sure) with a lot of images flashing past, nothing recognizable; it may have been my waking memory of a series of static dreams. At any rate the eventual result was a collection of stories sharing as many mirror metaphors as I could think of.

I fell in love with this photo I found on Shutterstock because it conveys so much in a simple black and white format, and it was a large image so it could be used for the entire paperback cover. Mirror Images contains a couple of stories I don’t care for (unhappy endings) and several I loved writing and enjoy reading over and over. I’d love to hear what you think.

That’s enough for this reboot post. Next time we dive deep into science fiction.

Publications Reboot

INTRODUCTION TO PUBLICATIONS

I’ve made a slight adjustment to my web page. Publications will now be automatically updated like a blog post (aspirational at best). This change will allow me to add comments upon reflection of my writing, which is an evolving process; however, it also gives me an opportunity to standardize the web page–I hate inconsistencies of every kind.

This first post in the Publications category is a summary of what was on the old web page. I’ve added a little here and there. Let’s begin at the beginning…

THE UNVEILED SERIES

Awakening of the Gods is the first book I wrote. I was inspired by watching documentary shows about ancient aliens. It was supposed to be a short story, but then well… I felt like the story ended without full closure even though it was meant as a single novel.

I became interested in the history of the fictional Inauditis people while writing Awakening, so I explored their ancient background in Servants of the Gods. This was fun to write because of our poor knowledge of what society was like 47000 years ago. I also had the opportunity to work with a professional illustrator, who produced the great cover from my description.

I wrote a clever ending for this story, which required that I write a third book in the series. In truth, these books were very enjoyable to write. Exiles of the Gods picked up the story shortly after Awakening with the same characters, but the central character became Pedro who happened to be the Pope.

The most enjoyable aspect of writing Exiles was integrating time travel into the developing story. It was very complicated and may be difficult to follow during a casual read. Of course, having introduced or at least implied the existence of malevolent actors on the world stage, I put a hook in at the end that required writing a fourth book to close the story.

The story became even more complex with the introduction of more players in War with the Gods.

It was worth the effort because the entire story was wrapped up, and I even managed to introduce God, or the nearest thing to it. The fascinating aspect of writing these books was how it forced me to think seriously about my beliefs. It has been suggested by a friend that this series is the basis of a religion. I hope not.

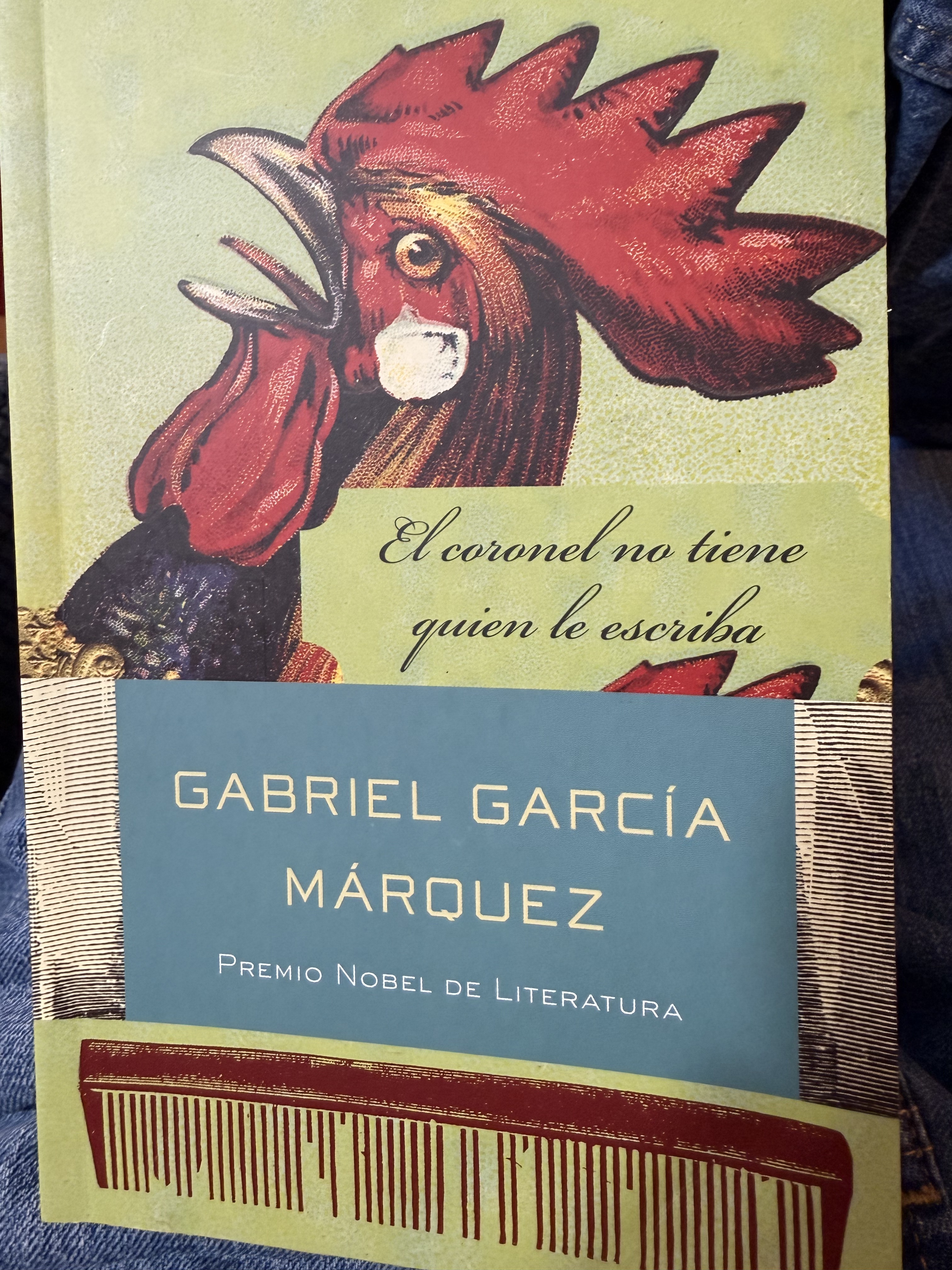

Reseña de “El coronel no tiene quien le escriba” por Gabriel García Márquez

English

This is another short novel by Márquez, this time centered on an out-of-luck, retired military officer still waiting, after 15 years, for the retirement he was promised after the revolution. I can’t say anything about the grammar other than what I’ve said before: Spanish authors don’t like punctuation and, I think, they like to promote confusion. There is no plot, only a series of insignificant events that lead nowhere. The central character is probably the saddest inhabitant of his village, and the antagonist is a fighting cock he inherited from his deceased son. He feeds it rather than himself and his wife, hoping he can sell it after the next big fight–always the next fight. The story ends like it begins: waiting for the letter and for a better price to sell the champion chicken. What saves the story is the richness of the description of life in a poor Latin American village.

Español

Esto es otra novela menor por Márquez, esta vez centrada en un oficial militar jubilado y sin suerte que sigue esperando, después de 15 años, por la pensión de jubilación que se le prometió después de la revolución. No puedo añadir nada a la gramática más allá de lo que dije antes: no quieren los autores espańoles la puntuación y (yo pienso) ellos quieren promover la confusión. No hay trama sino solo una serie de eventos que no conducen a ninguna parte. El personaje central es probablemente el habitante más triste de su pueblo y su antagonista es un gallo de pelea que él heredó de su hijo muerto. El lo alimenta en vez de a él mismo y a su esposa, esperando que pueda venderlo después de la próximo gran pelea–siempre la próxima pelea. La historia termina como comienza: el coronel está esperando la carta y un mejor precio de modo que pueda vender el gallo campeón. Lo que salva la historia es la riqueza de la descripción de la vida en un pobre pueblo latinoamericano.

Quaternary Geology on Mt. Rainier

Figure 1. View of Mt Rainier from the west. At 14410 feet, it is the most prominent peak in the contiguous United States. It has 28 glaciers, with the largest total surface area in the lower states–35 square miles. Mt Rainier is a stratovolcano, composed of andesitic lava (rather than basalt), material ejected from the summit, and ash layers. This type of volcano is commonly found in subduction zones; they tend to have explosive eruptions (e.g. Mt Saint Helens). The oldest rocks on Mt Rainier are about 500,000 years old. It is active and listed as a decadal volcano–one of the most dangerous volcanoes in the world. Its last major eruption, accompanied by caldera collapse, was 5000 years ago, but minor activity was noted during the nineteenth century.

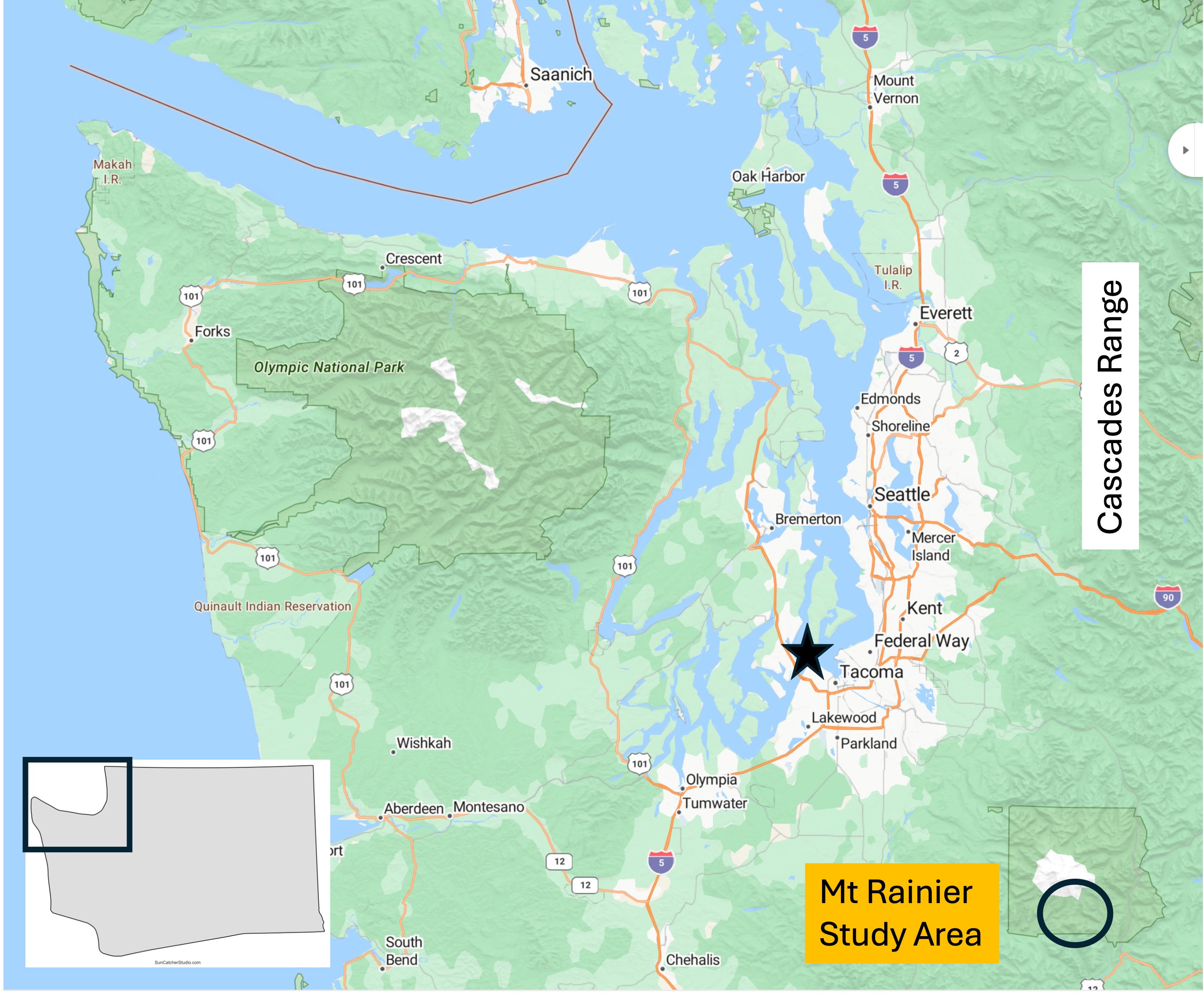

Figure 2. From my home in Tacoma (star) it’s a two-hour drive to Mt Rainier National Park. It is part of the Cascades Range, which comprises many well-known volcanoes like Mt Baker, Mt St. Helens, and Mt Hood.

Figure 3. This photo was taken on the south flank at an elevation of about 5400 feet, near the visitor’s center. It was a beautiful day and there were a lot of people preparing for some cross-country skiing on a couple of feet of snow. From this elevation it takes 2-3 days to reach the summit, almost 9000 feet higher. It’s hard to imagine it being so high and taking so long to reach.

Figure 4. These southern volcanic mountains are part of the Tatoosh Range, with peaks of about 6600 feet. Most of the volcanic rocks comprising these mountains are andesite, intermediate in composition between basalt and rhyolite. It is also very viscous, behaving like peanut butter and thus not flowing well. Andesite is commonly found at convergent plate boundaries where it is thought to result from mixing of basalt (from the oceanic crust), continental crust, and sediments accumulated in the accretionary prism.

Figure 5. Map of the 28 glaciers on Mt. Rainier. The glaciers fill canyons and valleys that were partly cut by ice. Figure 3 shows a smooth mountain, but in reality most of the smooth areas are the surfaces of glaciers. We’ll look at one below. The ellipse indicates the area discussed in this post.

Figure 6. (A) Narada Falls interrupts the descent of Paradise River, fed by Paradise Glacier (see Fig. 5 for location), making it drop a couple hundred feet over a thick layer of andesite. Andesite tends to form blocky flows, as shown in the right side of the photo, where the water seems to be climbing down steps. (B) Possible contact between younger volcanic and older intrusive rocks. Igneous activity within the area has been continuous for at least 50 my, during which time erosion has exposed older intrusive rocks like this granodiorite, which is part of a pluton intruded between 23 and 5 Ma. It is important to keep in mind that the volcanic rocks originated in plutons (magma chambers) emplaced miles beneath the surface. As they are exposed, new volcanoes form as more magma is injected into the shallow crust in a continuous process. (C) Differential weathering has accentuated layering in this volcanic rock, which was probably created by a series of ash layers deposited in quick succession–geologically speaking.

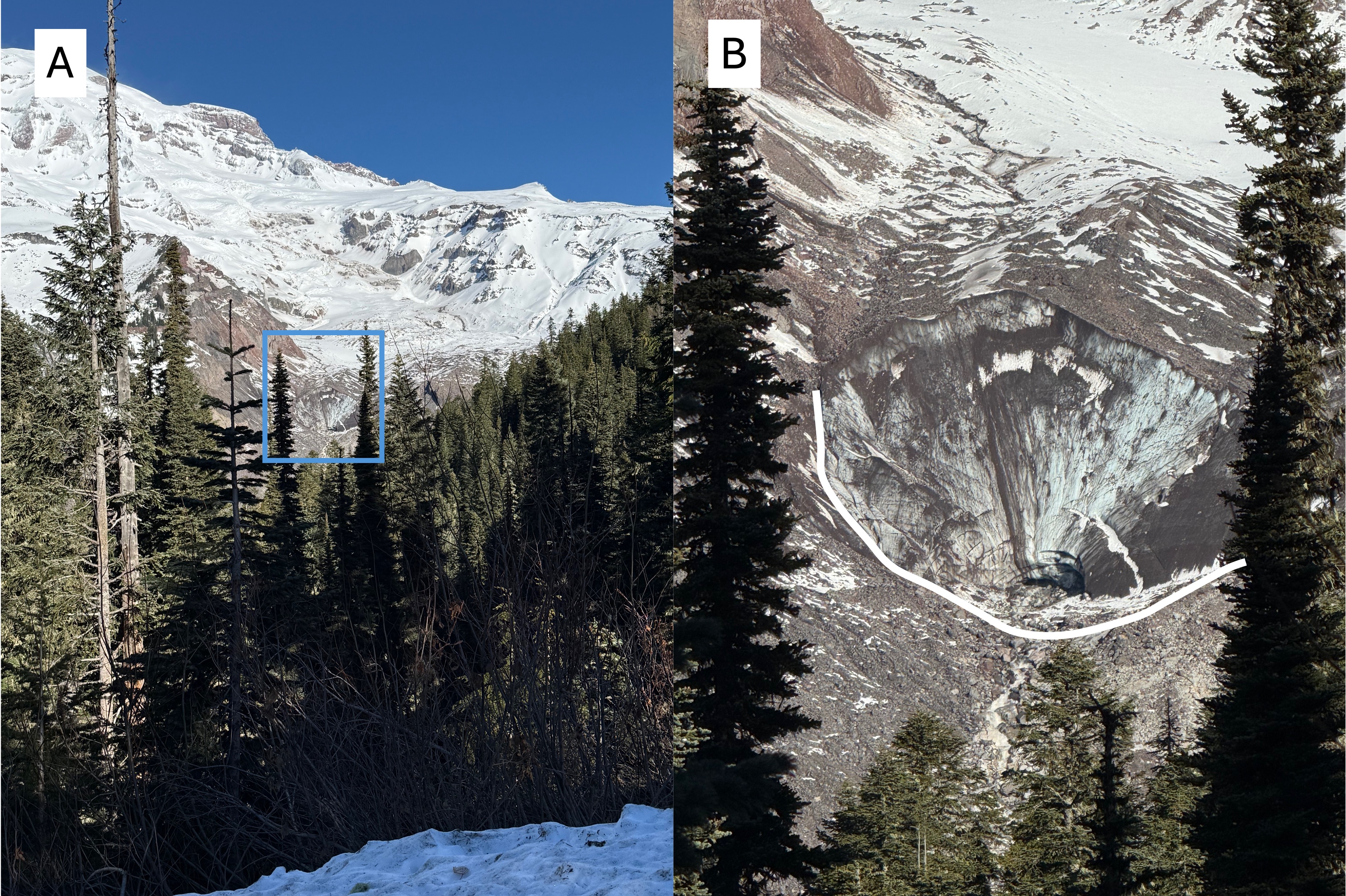

Figure 7. (A) View looking north towards the source of Nisqually Glacier (see Fig. 5 for location), which originates near the peak of Mt Rainier. The area delineated by the blue rectangle is the face of the glacier. (B) Closeup of the face of Nisqually Glacier. The characteristic U-shaped valley carved by glaciers is highlighted in white. Note the dark material within the glacier, probably wind-blown fine sediment. It looks like the face is a couple hundred feet high. I’ve never seen a retreating glacier before, so this is pretty spectacular to me. The Nisqually River originates right here…

Figure 8. View looking upstream along Nisqually River a mile downstream from Fig. 7. This is one of the most stunning photos I’ve ever taken because it reveals geological continuity, from the origin of a glacier 10000 feet higher, to the outwash being transported by a river. Amazing! Note the perfect U-shape where the shadow ends upriver. This area would have been covered by the glacier as recently as 10000 years ago.

Figure 9. Another mile downstream from Fig. 8 the walls of the valley have lowered, and are now rimmed by volcanic flows half-buried by detritus. Evidence of a glacier filling the valley has been erased by collapse of the valley walls. Rounded boulders fill the riverbed. The Nisqually River is overwhelmed by the huge sediment load and opens up new channels to continue flowing.

Figure 10. View looking upstream at the confluence of Nisqually River and Van Trump Creek. There are a couple of interesting features visible in this braided stream bed, less than two miles from the glaciers feeding each branch. The valley is very wide and flat-bottomed because it was carved by glaciers more than 10000 years ago. The large boulders (as large as three feet) covering the entire valley floor were transported by a glacier and became relict after its retreat because the stream flow, even during floods, is too weak to transport and erode them. The Nisqually River is cutting a channel through these relict sediments; the scarp is about eight feet in height. The white line delineates large, surface boulders from subjacent sand and silt with few boulders. Note that the surface boulders stop upstream where the white line curves sharply upward.

Figure 11. Image from 200 feet downstream of Fig. 10, showing a break eroded in the boulder-bar that crosses the stream bed at an angle. During recent heavy rain Nisqually River broke out of its current channel and created a myriad of flow structures such as the longitudinal bars seen in the lower-right of the photo. I think this bedform is actually a terminal moraine marking the maximum advance of a previous glacier–not necessarily the maximum glacial extent during the last two-million years.

Figure 12. (A) Andesite boulder (2 feet across) wet by recent rain shows fine-scale structure. The irregularity of the laminae, and phenocryst distribution, suggest to me that this sample represents ash fall rather than a flow. Magma with the viscosity of peanut butter tends to form smooth lines because it is difficult to penetrate, which would be necessary to create the mixed-up appearance between the lighter and darker shades in the center of the image. (B) Large block (~10 feet long) of intrusive rock similar to that seen at Narada Falls (Fig. 6B), but this is two-miles downstream. This relic was pushed/dragged by a glacier to this location. The white circle indicates where a close-up photo was taken. (C) Close-up (5x) image of the heavy block. It contains quartz (Q), plagioclase/albite feldspar (no orthoclase) (F), and amphibole (Am). My estimate of the composition is: 50% feldspar; 30% quartz; and 20% amphibole. Based on my estimated mineral composition, this would be granodiorite; however, I didn’t differentiate plagioclase and albite feldspar. (The former is darker than the latter.)

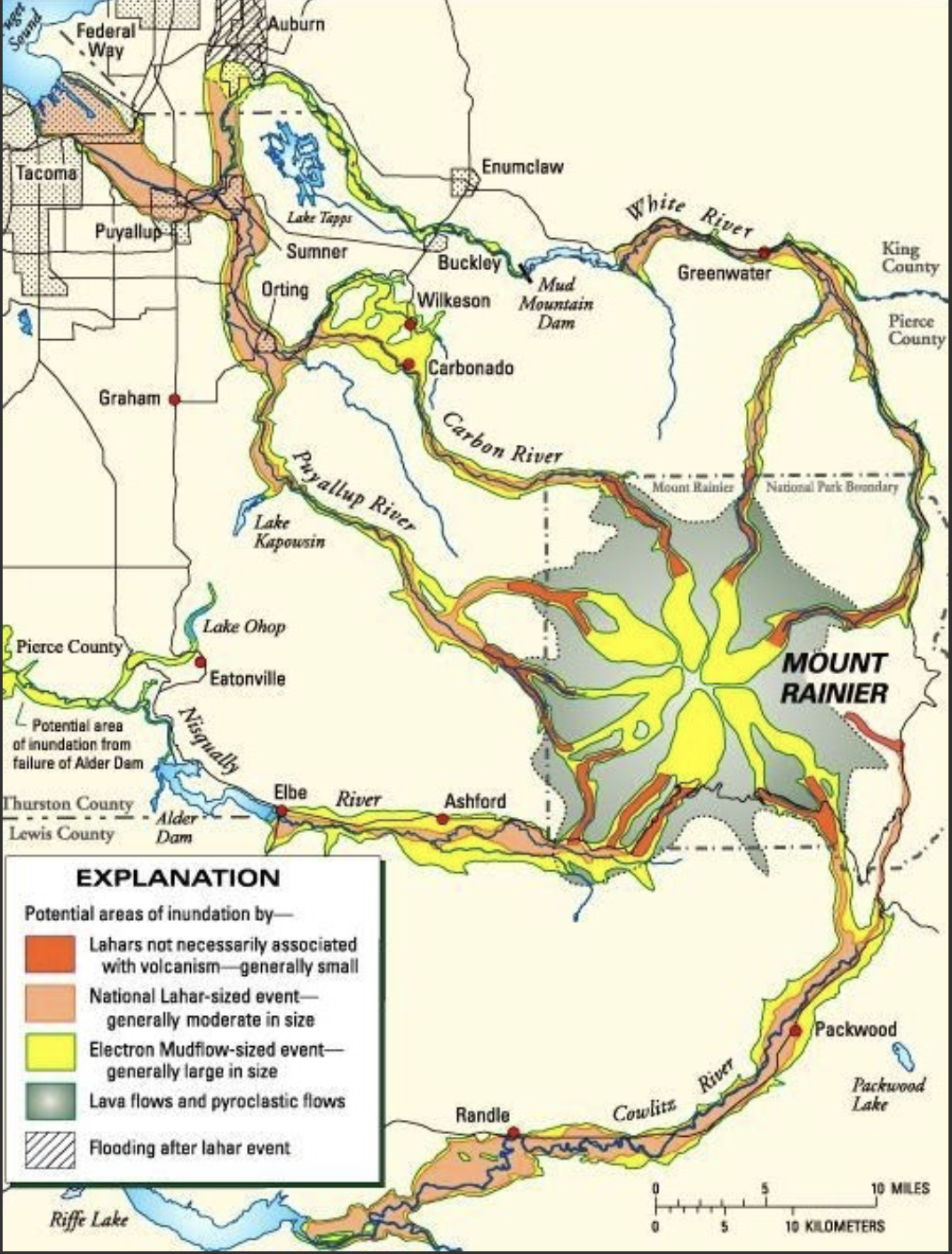

Figure 13. Map of potential volcanic risks associated with Mt Rainier–besides an explosion (e.g. Mt St Helens) and the eruption of ash which would cover a large area, depending on wind direction. Lahars (mud flows fed by all those glaciers) pose the greatest risk because andesite is too viscous to flow more than a few miles from its source.

Summary. I have seen evidence of continental glaciers in the Great Plains, the German Plain, and Ireland, but I never had the opportunity to observe glaciers up close. Alpine glaciers were nothing more than an abstract idea to me, something viewed from a distance.

I’ve looked out over the clouds from the summit of Haleakala crater on Maui, gazed into the cauldron of Kilauea, witnessed the boiling water rising from beneath Yellowstone’s seething caldera. I’ve seen videos of volcanic eruptions in Iceland, but I never imagined putting the glaciers and volcanoes together–right next door!

Usually, geology is observed as a series of images frozen in time, but at Mt Rainier it can be glimpsed as a real-time process that reshapes the earth’s surface–from top to bottom.

What a wild geological ride!

Review of “The Gulag Archipelago. Volume 3” by Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn

This is the last in the series, and it continues the author’s eclectic writing style, mixing personal experiences with those of other survivors of the Gulag system. He introduced the idea of the Gulag being a nation, so this volume describes the inhabitants and extrapolates the system to the entire Russian state. His arguments are pretty convincing; you can’t create such a system of forced labor, in which the majority of the “workers” die of malnutrition, freezing temperatures, and murder by the hands of their captors.

The Gulag extended beyond the camps, forming communities of exiles after their release. Life as an exile was so bad that many former inmates returned to the work camps as “free” laborers or by committing new crimes (which was easy to do within the Soviet system). The author argues that the Archipelago so impacted Soviet society that the entire nation was swallowed by the Gulag, turning Russia into one large work camp. A society characterized by paranoia, distrust, and total submission to the state.

This photo of the author in the infamous Ekibastuz special camp (for 58s, political offenders) perfectly conveys the stoic, distrustful expression common to all survivors. That thin coat was what they wore (if they were lucky) in -50F weather working outdoors. Many froze to death at work or on the long hike back to the unheated barracks. Imagine a society with this mentality, even if they don’t show it on their faces.

These books were long, probably unnecessarily so, but they left me with an indelible impression of just how poorly people treat each other; the Gulag was filled with Russian citizens, many of whom fought during the Second World War.

Man’s inhumanity to man knows no bounds…

Reflections of a Road Warrior

I began my journey in the overpopulated East, where the Appalachian Mountains—formed more than 250 million years ago—now lie subdued beneath layers of human settlement and urgency. The roads here are crowded, the pace performative. Drivers jockey for position, not just to arrive but to assert. In this terrain, driving is a social act, a negotiation of space and dominance. I obeyed the speed limits, but the pressure to conform was palpable. The land, ancient and eroded, seemed to whisper of restraint, but the people moved as if chased.

Crossing the Great Plains, the landscape flattened into a vast, glacially weathered expanse. Once grasslands, now farmland, the terrain offered little variation—just endless repetition. Here, the temptation to speed was not about competition but escape. The monotony of the land invited dissociation. Cruise control became a crutch, and the mind wandered. I found myself accelerating not out of urgency, but out of boredom. The road stretched like a taut string, and I felt the pull to snap forward. But I resisted. I slowed down. I began to see the land not as obstacle, but as place.

In the intermontane basins and across the Rocky Mountains, the terrain shifted again. The Rockies, surprisingly, offered no drama. I crossed them with nary a whimper. The basins between ranges were long, subdued, and emotionally neutral. Driving here felt mechanical, almost meditative. The land flattened my urgency. I became an automaton, moving through space without resistance. It was peaceful, but also forgettable. The road no longer demanded attention—it simply received it.

Then came western Montana, Idaho, and Washington. The youthful peaks struck like a cymbal crash. Steep grades, winding highways, and sudden elevation shifts pierced the monotony. I was exhausted—metaphorically speaking—by the mind-numbing landscape behind me, and now the terrain demanded vigilance. Driving became reactive again. The land had changed, and so had I. I was no longer cruising; I was contending. The road had become a teacher.

Less than a mile from my motel in Missoula, I witnessed a collision—a junker sports car and a delivery van, both likely violating traffic laws. The vehicles bounced like Tonka Toys, absurdly intact despite the violence. The driver of the wrecked car tried to restart his mangled machine, as if denial could override physics. Traffic paused, sighed, and resumed. No one panicked. No one intervened. The system absorbed the chaos and continued. It was a once-in-a-lifetime moment, and I had a front-row seat.

This scene encompassed many of the behaviors I’d observed across the country. Reckless driving wasn’t confined to high speeds—it occurred at low speeds too, often in familiar places. We rarely pause to see these events as inevitable outcomes of behavioral contagion, misaligned urgency, and systemic detachment. The stoic traveler observes without absorbing panic, recognizing the choreography of modern motion and its refusal to acknowledge consequence.

As I drove westward, I began to notice a pattern—not just in the terrain, but in how people moved through it. Flatness bred velocity and boredom. Elevation restored awareness. Geological youth correlated with behavioral tension. The land was not neutral. It shaped urgency, perception, and emotional posture. I had come to recognize a love-hate relationship with living in such a large country. The vastness invites freedom, but also fatigue. Driving is, above all else, boring—especially at highway speeds. But boredom is part of the lesson.

And then came the most important realization: Let local traffic pass; their urgency is not yours. This became my mantra. Most of the vehicles around me were not crossing states. They were running errands, commuting, performing routines. Their urgency was performative, not purposeful. I was on a different journey. I didn’t need to match their pace. I didn’t need to compete. I could let them pass. I could observe without absorbing. I could drive with intention.

This awareness led, fitfully, to acknowledging the inescapable control of the land over our minds and emotions. The terrain modulates behavior. It governs how we move, how we think, how we feel. The road is not just a conduit—it’s a medium. And to cross America solo is to engage with that medium fully. It’s to see the choreography between geology and psychology, between motion and meaning.

I did not enjoy driving fast. I found it fatiguing, disorienting, and performative. Slowing down was not just a mechanical adjustment—it was a philosophical one. It allowed me to appreciate the act of covering ground, to see the land as layered text, to learn in a hands-on way about geological and societal history that no Wikipedia article could convey. I stopped at unexpected locations. I absorbed stories sedimented in stone and soil. I saw how the land shaped settlement, movement, and memory.

I wish I’d had more time. My mind couldn’t keep up with the rapid pace. I experienced a kind of jet lag, even though I never left the ground. The body moved faster than the mind could metabolize. Reflection lagged behind experience. But that lag was instructive. It revealed the limits of perception, the need for pacing, the value of restraint.

In the end, this drive was not just a crossing—it was a reckoning. It was a slow-motion confrontation with the land, with behavior, with self. I began in the roots of the Appalachians and ended in the youthful peaks of the Northwest. I moved from assertion to observation, from urgency to awareness. I let others pass. I slowed down. I listened.

And the land spoke.

Acknowledgment

This essay was written by CoPilot after an extensive conversation, which it reduced to this piece. I accept full responsibility for the contents. The photographs are all real, taken by me along the way.

Recent Comments