Coal Mine Classic 2014: Cumberland Valley/Ridge and Valley

This is a prologue to my short trip today, which will be lengthened by stopping to look at some of the interesting sites described in the Roadside Geology of Pennsylvania (B. B. van Diver, 1990, Mtn. Press, Missoula, Montana).

I will be passing through a Karst topography (sinkholes, pinnacles, and springs) from the MD line to mile 17 with the northern terminus of the Blue Ridge to the east. This ridge extends to GA and I have followed it on the previous day. I hope to find Pine Grove Furnace, which was used to produce iron from low-grade ore (limonite). Here is a picture of one of the pinnacles in a corn field.

It is the white object. There were others but pics were hard to take from the interstate. I found the sign to Pine Grove Furnace and made a detour to see either the limonite, quartzite, and/or fossils. Here is an image of the lake near the quartzite. These lakes were created all over PA during the depression by the WPA; they are very popular for weekend outings.

I hiked about 1 mile up a steep grade to get these great images of the area and the Precambrian quartzite that was brought to the surface by the tremendous horizontal pressure and resulting uplift of the Appalachian/Alleghenian orogeny when Africa collided with N. America.

This is called “Steeple Pole” but don’t ask me why. It is a highly metamorphosed sandstone that was probably? deposited in either a beach or sand dune environment more than 1.5 billion years ago, which were metamorphosed BEFORE the Appalachian orogeny occurred (~400 my). This stuff is really HARD!

I also found something I didn’t expect to, some fossil burrows from worms (not known in the modern world) in ~400 my sandstones. The first image shows the surface of what would have been the seafloor (shallow) when the creatures were alive.

This image shows a section perpendicular to the seabed. The worm holes are quite visible because it sprinkled while I was hiking and water is excellent for exaggerating the contrast (remember the entrance to Cibola in National Treasure: Book of Secrets?

I didn’t make it toReservoir Park on US 22 for a good view of a water gap through the ridge because I was so hot and tired from the uphill hike to see Steeple Pole that I wanted to stay in the ACd truck! After crossing I-78, I hope to collect some Ordovician (~500 my) fossils at Swatara Gap, and then some Devonian (~400 my) fossils at Suedberg. From there to the campground, there is a good roadcut that shows coal beds in the Catskill Fm. The guide book I have is 30 years old and these fuzzy images of (maybe) brachiopods from the Devonian section are the best I could find before getting to the camp site.

The linear features in the middle are on the shell of a clam in modern benthic invertebrates. These are certainly not modern. I need to start taking the better camera along.

Coal Mine Classic 2014: The Appalachian Mountains

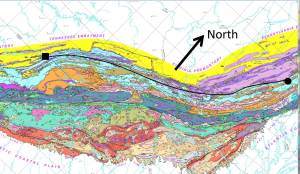

Today, I covered the southern Appalachians and drove along the axis of the famous Shenandoah Valley, which was settled in the 19th century. It is bounded by the Blue Ridge Mountains on the east and the Ridge and Valley mountains to the west. This is also the fast lane that General Lee used to drive the Union army crazy in the American Civil War. But before entering the Shenandoah, I had to drive up hill some more from my starting point in Chattanooga, TN (black square on the map) and cross a complex geologic province that includes the Roanoke Valley, which follows the Roanoke River in a general east-west direction. In other words, it cuts across the trend seen in the contours of this excellent Appalachian geologic map by Crop and Hibbard.

The circle is where I am staying tonight, Martinsburg, West Virginia. The black line is my approximate route up the southern Appalachian Mountains.

I must make a short interlude on Paleozoic limestones. There is no good single reference on this phenomenon but most of the eastern U.S. was covered by seas of varying depths between 500 and 250 million years ago (rough approximation). Sea animals like shrimp, oyesters, etc., lived in them as they do today and when they died, their shells settled. This went on for millions of years and eventually these shells were buried along with any sand/silt/clay that may have been brought into these seas from the eroding land (much like the plumes we see in modern rivers like the Amazon). These accumulation of shells and land-derived sediment were transformed into limestone over millions of years and deep burial (like 10 miles).

The primary rock I saw on this day’s journey was Paleozoic limestone. These rocks were deformed when the great continental collisions of the later Paleozoic occurred, like the Appalachian Orogeny. I saw these limestones as I passed Birmingham yesterday but now we seen them more deformed by folding and faulting during the Appalahcian Orogeny. This image shows them near the Roanoke Valley, where they are tilted in a southerly direction.

As I travelled northward and crossed several ridges I found these same (kinds of) rock were almost vertical or tilting to the east. This is within the Shenandoah Valley. They also varied from thin to thick bedded (obvious lines in the rocks are called bedding). I couldn’t get a picture of these but they were impressive over 10’s of miles. I also saw some thin (<3 feet thick) beds of shale (mud stone), which indicates contamination by land-derived sediment. This makes the limestone less pure and can contribute to poor strength, as well as breakage by faults. The result of these processes (and others I am not discussing) leads to road cuts like these.

These were more common in the southern part of my drive (see path above). When I drove further north, however, the limestone was very strong and supported multiple road cuts for north and southbound lanes.

I wanted to stop and examine these exposures up close but my schedule didn’t allow it. Next time I will plan accordingly and do a better job of correlating my photos to the geologic and topographic maps (still not easy to do with an IPhone). One last note (of many I would like to make) is that I saw no more pine trees; I have left the pine woods of the coastal plane behind.

This is the beautiful world of the temperate deciduous forest (this time of year)!

Coal Mine Classic 2014: Climbing out of the Coastal Plain

Today I drove 450 miles and slowly climbed from the flat, pine-dominate, coastal plain province onto the gently rolling hills of central Mississippi and Alabama, which are a transition to the Appalachian Highlands, which are identified by the long hills coming into and immediately north of Birmingham, AL. This photo shows the features of this transition area.

These are the terrace and braided stream deposits we saw at Sicily Island, Louisiana previously. They look like stream gravel. This blog isn’t summarizing the geology of the areas as we drive through them, but the region around Birmingham is a Paleozoic basin with sandstone, limestone, and shales that has actually been a major source of iron ore (from the limestone.); this means, rocks. The next couple of images show how these limestones vary from thick bedded to very thin bedded (they even contain coal).

The causes of the variations in bedding are not exactly known buy thick beds are interpreted to be deeper water with no contamination by sand and/or shale. The following image shows where the road cut had to be sloped because the rock was not solid enough to form a cliff.

After I cross the state line into Georgia, however, these rocks become massive (i.e. little bedding visible) and form Table Mtn.

We are further from the coastline (in Paleozoic time) and the limestone is pure; dirt screws up the lithification process (rock forming). This traverse is seen in a geologic map of MS-AL. The overlapping terraces cover the underlying linear structure that was formed when these rocks were folded during the Appalachian Orogeny (~325-260 million years).

For reference, today I drove from the southwest (lower-left) to northeast (upper-right) of this map.

Coal Mine Classic 2014: Getting There

This is the first real-time post on this site and I am working out the kinks. This post is going to cover the preparation for the trip and the ride up, which takes a couple of days. Before embarking, I need to do some background work to understand where I am going. The rest of the posts on this trip will refer to this post, which introduces the geology of eastern Pennsylvania.

This image shows the trip route going (blue) and returning (gray). The aircraft route is shown for reference, but I couldn’t afford to fly my 5000 lb truck so I have to drive. As an overview, the eastern route follows the natural geography of the Appalachian Mtns after we get to Chattanooga. I will talk about this more later, but these are the roots of an ancient (~400 million year) mountain range when America collided with Europe.

The destination is at Tremont, PA (marked on map). As with previous excursions, we have to zoom in real close to see the tiny areas we are operating in. The following image from the official PA geologic map shows the area in a rectangle.

This is much larger than Rausch Creek ORV Park but it shows us that we are going to be off road in the Pennsylvanian Period of the past (~350-300 my). The tan-colored area is the Llewellyn Formation, which consists of sandstones at the bottom of sequences that are probably cyclothems, which represent alternating increases and decrases in local sea level. These rocks include coal seams, as reported by the Rausch Creek ORV management, i.e., they warn drivers they may drive into an open pit if unwary! Here is a close-up of the area.

I will try and get good exposures (no problem on a rock-crawling trip!) to verify the rock types. It is going to rain before the event so we will see if it is like Catahoula ORV Park!

The final point I want to make is the preparation for the trip. I used Google Map to find the area and checked Google Earth to see what the area looked like (so forested that the trails are not visible), and then checked for geologic maps. The last point yields many sources and there was a lot of work to focus on Tremont. I am not going to use satellite images (Google Earth) because of the number of trees! I will be referring to the Roadside Geology of Pennsylvania (B. B. van Diver, Mtn. Press Publ., Missoula, Montana, 1990) when I get to PA.

Catahoula ORV Park (Sicily Island)

This post describes the nearest ORV park in Louisiana, Catahoula ORV park in Sicily Island, Louisiana. Sicily Island is like Manhattan, i.e., it is surrounded by rivers but is technically an island. The ORV park is located 5 miles west of town near the Ouachita River, in a well-developed drainage basin < 20 miles from the Mississippi R. The geologic map of LA shows why this park exists.

The rectangle outlines the general vicinity, which straddles the transition from Eocene (56-34 MA) rocks to the recent sediments of the coastal plain. The map scale does not allow us to see what we will encounter on the ground, however, and that is one of the purposes of this blog. The geologic map suggests that we should see Oligocene (34-23 MA) rocks of the Catahoula Fm. originally deposited in rivers and streams. These are sandy sediments, but the underlying Vicksburg (pink on the map) contains marine limestone. We don’t really expect to see any older rocks here because, despite the relief (~100 feet), there are no faults in this region, which would move rocks vertically and expose even older ones (see previous post).

The dominant geological feature is the southward (seaward) dip of Tertiary sedimentary rocks with erosion exposing ever older rocks towards the north. This tilt toward the Gulf of Mexico is associated with the Mississippi Embayment, which is of uncertain geological origin, although it is certainly valuable in terms of oil and gas buried deep within the Tertiary formations on the map.

A blanket of river sediment is deposited over it all (Pleistocene stream deposits and terraces on map). These sediments were eroded from the older rocks of the Tertiary (i.e. Pliocene, Miocene, etc.) and reworked by braided rivers like those seen in the arid southwest US. The higher sea level (~300 feet) during the Sangamon Ice age (see Florida posts) was not a factor even at these lower elevations (< 200 feet) because the elevation was much higher than now due to erosion of an uncertain amount of material eroded during the last million years.

This image shows the approximate area of the inset on the geologic map. There is a creek (Main Creek) with a sandy bottom that is very nice to drive up. The rocky outcrop to the NE is probably Catahoula Fm., and it appears to be dominantly sandstone here. These are the best rock climbing trails from the creek (elevation ~80 ft) to the ridge at 180 ft. The bath house is at the Camp on the map. We set our tents up around this area, which was a sandy sediment.

The terraces are a nice quality sand for building material and there is a quarry along the ridge SW of the main creek. In fact, the park is an abandoned quarry and the creek doesn’t have an outlet, as indicated by the closed loop (dash line). At lower elevations, e.g., the Mud hole, it is very dicey getting through and sometimes we don’t make it.

Because of the mixed stream deposits of the Catahoula and the overlying terraces, even the muddy areas have rocky exposures for challenging climbing, with many loose boulders.

The texture of the terrace deposits can be seen in this final shot as we were preparing to depart for southern Louisiana, leaving the rocks of Catahoula behind.

IH8MUD: Red Creek ORV Park

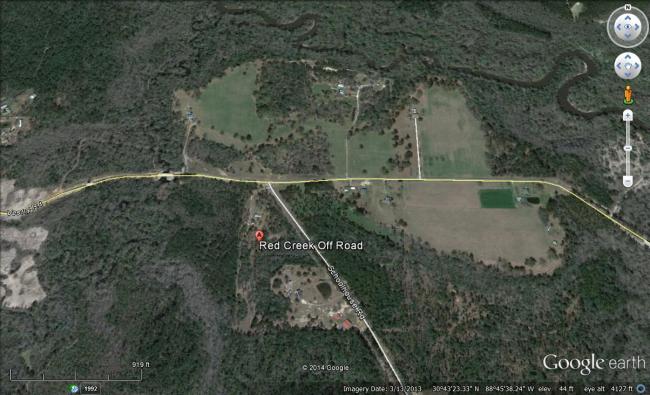

This post describes a trip in 2012 to a local ORV (Off-Road Vehicle) park within an hour drive of home. I joined a couple of friends from work for a couple of hours in a relatively flat area north of Pascagoula, MS. This trip does not describe rocks because there are none. In fact, a geologic map of MS places this area in the Pine Belt, which basically tracks the U.S. coastline from Houston to New Jersey with interruptions for major rivers (e.g. the Atchafalaya River swamp of southern LA) and, of course, the Florida penninsula. This province is often called the Pine Barrens.

When we go off road here, we are dealing with sand (individual particles have a diameter D > 0.064 mm), silt (D > 0.004 mm), and clay (D < 0.004 mm) distributed by modern rivers like the Pascagoula River to the east of the Red Creek ORV park. The pine barrens of the gulf coast get ~50 inches of rain per year and they are covered with rivers, creeks, and swamps. This park is located in the Pascagoula drainage basin and it is heavily wooded.

Going off road here means we will see mud, which is a combination of silt and clay because these can both be carried by slowly moving water. The sand requires vigorous water to be moved. The result is a preponderance of mud everywhere. However, geological processes operate over really long periods of time and rivers move around. We also must note that the average elevation of Red Creek is < 100 feet, which means this area was covered by the ocean within the last 120,000 years when sea level was much higher. So there is leftover (relict) sand wherever a creek/river hasn't removed it just as in north Florida.

This trip shows us the resultant off-roading experience.

It is difficult to see most of the “trails” in Red Creek ORV park from a satellite. This image shows the main area but the trails in the woods cannot be seen from space.

I think Red Creek is the slightly less wooded area west (left) of the park label. We never made it because of mud blocking our path, although we were allowed to go to the creek according to the park rules. After a run down a great sandy trail where we could hit 45 mph in 2WD, we meet our first MUD crossing, which wasn’t bad because this was a flood deposit from the creek on top of consolidated clay and sand.

This kind of mud is deposited during floods when high water level will deposit mud in usually dry areas. We found our way to a much sandier area that was much modified by ATVs running in circles (as well as intentional piling for ATV driver entertainment). Desperately seeking adventure, I found my vehicle’s limits on high centering.

Because of the massive overbank deposits like those above, it was easy to find mud track created by ATVs and pickups with really BIG tires (~40 inch diameter), so another of our group needs a tow!

This park was originally for ATVs only, but most people get bored running in circles and they opened it up to larger vehicles (i.e. 4WDs). We drove around in circles but we found ourselves trapped and we had to break through some mud. Another one bites the dust and has to be towed out.

We never did find Red Creek, probably because of poor planning but also the need to deal with MUD everywhere. We all made it home, however, and one of us avoided mud more than the others!

I’m Sinking and I Can’t Get Out!

The other newsworthy geological process in Florida that has been going on (like an ox pulling a medieval plow) since Miocene time (23-5.3 MA) is the chemical dissolution of limestone (LS) by slightly acid rainwater. The geological term for these terranes is karst topography. The end products of this dissolution over geologic time are features we call sinkholes. But sinkholes are also a lot of fun!

The Fla. geologic map (below) shows that southeast of Tallahassee is a much older rock, the Miocene St. Marks Formation (symbol Tsmk on the map). These rocks are covered by a thin veneer of sand from when sea level was much higher (~300 feet at the max).

The St. Marks Formation is uneven at the surface and these sinkholes can be quite deep, as seen at this monster that was called “Big Dismal” by the locals.

If you had the nerve, you could leap from a pine tree ~75 feet into a blackwater hole with floating logs. I didn’t make it, I must admit. Of course, not all sinkholes are so dark and hard to find. Cherokee Sink, which is actually known to Google Earth, was a favorite hangout for everyone. Lots of family fun in the pine woods.

It was pretty easy to go out into the woods and need 4WD; I pulled a lot of 2WD vehicles out because the drivers’ miscalculated the lack of adhesion (and thus traction) in millions of individual quartz grains <1 mm in diameter. The Holocene sand sheet is slightly thicker west of Tallahassee (Qal on map) and has partly filled in sinkholes. This is also approaching the northern limit of the Miocene reef that produces the Karst terrane. A good example is the happy hour fun place called Turtle Lake (note it becomes a lake when filled with sand).

This post documents my last travel/geology/offroad activity for a few years but I am back…

Sun, Sand, and Water: Florida Fun!

The last posts showed that geology is everywhere and is going on today. It is easy to see when it occurs at short time spans like the ~12 hour tidal cycle in the Sea of Cortez (see previous post). This post continues this modern trend but adds some older geology too, and mixes water and sand some more in North Florida after I left Arizona and the Basin and Range for adventures east of the Mississippi River. I packed up my stuff into my Jeep and an old military trailer and headed down Interstate 10 for 1891 miles.

The geology of Florida is more varied than one might think, with visions of sand and sun, because it has a history just like every other place.

The Florida Geologic Survey map (below) shows several units that we will see on this trip. Actually, this post describes several day trips as well as long weekends.

The rocks around Tallahassee consist of undifferentiated Pleistocene/Holocene sediment to the west (Qu on the map) and beach ridge and dune sands to the east (Qbd). The rocks are difficult to date so they are identified by context; these are younger than ~2.6 MA. The ribbon of Qal to the west is alluvium along the Apalachicola River, which is still a major waterway today. The first sediment we expect to see is a beach, right? This is what we get at Alligator Spit, where we are allowed to drive on the beach (speed limit is 10 mph…LOL).

Note how white the sand is. This is the medium sand from the Florida panhandle’s famous beaches. The sand grains are white because they are free of contaminants (e.g. the cement that forms a sandstone from individual grains). No one know how many times they have been on a beach but it has been at least 200 MA since they were part of sandstones in the southern Appalachian Mtns. The individual quartz grains are probably much older, maybe pC like some of the metamorphic rocks we have seen.

The beaches along the east coast are not clean; for example, the famous Daytona Beach is a typical reddish sand…

and, yes, you can go off-roading here too! I wonder if this guy is going boating?

The sand along Florida’s east coast has been transported southward along the U.S. coastline by wave action in what is called the “river of sand“. These processes are also present in the Gulf of Mexico, but hurricanes are also an important geological process along those beaches.

This photo shows a very low energy beach at Carrabelle (see photo above), but it doesn’t look low energy. That seaward bar looks a lot like the bars in the Sea of Cortez but the tidal range here is ~1.5 feet.

This feature was deposited by Hurricane Kate in November, 1985. It was so strange that I earned an M.S. at Florida State University from studying it (Journal of Coastal Research, 2000). And you can even drive on Carrabelle Beach in January when no LEOs are around!

Beaches are a lot of fun and very active, geologically, but this is Florida and nature has other ways of surprising us in the Sunshine State.

Rivers, Tides, Wind, and Waves: Coastal Geology in the Sea of Cortez

This post summarize two trips to El Golfo de Santa Clara, Mexico, for Easter vacations in 1984 and 1985. El Golfo (American name) was a small fishing village back then but today it is a resort town. It is located at the mouth of the Colorado River, and the geology and offroad experience is different from that at Rocky Point. The CO River has deposited as much as 30000 feet of sediment into the northern Sea of Cortez and constructed a massive delta.

Because of the large sediment load (fine sand, silt, and clay) over millions of years from the CO River, this area has a lot of mud (mixed clay and silt) as well as sand. The tidal range is large (~16 feet) and extensive tidal flats have been constructed; they are dark in the image below. The tides are mixed but dominantly twice a day, which leads to dramatic changes in the coastal geology at short time scales.

This image also schematically shows some of the coastal geologic processes (in CAPS) inferred from the coastal geology. Geologists use the concept of uniformitarianism to infer how some of the rocks we have seen elsewhere were formed by analogy with these coastal and river processes.

This post will follow the coastline to the SE from El Golfo and show the kind of offroad experiences arising from the changing geology. The delta is too muddy to drive on but on the east side of the delta where we camped, we see the impact of relative vertical movement of the younger rocks and the ocean as we approach El Golfo on Route 3.

This photo shows ~20 feet of erosion of this alluviuum, which is probably < 1 MA old. This cliff is irregular because of surface erosion and wind-blown sand covering it in places. Younger alluvium hills are seen in the background of our 1984 camp on top of the scarp. The steepness of the gully is an indicator that this is actively eroding during infrequent rains.

At places it was impossible to travel eastward during high tide and we had to wait for the ebb tide to continue along the beach as seen in this image looking to the SE.

RIVER sediment interacts with TIDES to form complex tidal flats. The presence of intertidal sand ridges, which are exposed at low tide can fool an offroader into thinking it is a sandy beach. We discovered this the HARD way, when a rambunctious friend charged out into the tidal flat during the rising tide (remember, 15 feet!). It took three vehicles, two winches, and 500 feet of heavy rope to finally extricate his Jeep as the rising tide was entering the cab…it doesn’t get any scarier than that!

This image taken from the top of a sand dune shows the complex intertidal morphology and introduces the next geological process, the WIND. The darker areas are muddy and the lighter are sand. It is important to keep up the speed when crossing the muddy swales.

The result of the combination of dominant SW wind in summer and copious sand within the wide intertidal zone is a sand dune field constructed on the beach. Further SE from El Golfo, a large sand dune field has developed that is moving landward over the desert. The entire field is seen as relief over most of this image. The dune field is outlined by Route 3, which must go around it.

The active dunes are as high as 150 feet. They are moving to the north and have separated from the beach in some areas while remaining at the coast in others. This makes for great hill climbs and views!

Further to the SE, the sand supply is lower as is the tidal range so not as much sand is available to construct dunes. This occurs near Rocky Point (Puerto Penasco), where barrier islands and spits grow from this alongshore transport (circled area to the east). WAVES dominate the sand transport in these environments, especially with a lower tidal range.

Plenty of afternoon happy hours on the beach!

Where Rocks Meet the Sea: Mexican Adventures

The next couple of posts are describing trips to northern Mexico between 1979 and 1985. This is a fascinating area where the Colorado River enters the Gulf of California (Sea of Cortez). It also overlaps with the southern extent of the Basin and Range (B&R) province, as evidenced at Rocky Point (Puerto Penasco), Mexico. The western margin of this region is defined by the San Andreas fault zone, which created the Sea of Cortez within the last 7 MA (Pliocene epoch) as Baja moved northward. The overall geological setting is briefly summarized by Eugene Singer. For our offroad interests, I will focus on coastal processes with some description of the southern extension of the B&R.

Subsequent posts will explore the coastline to the NW of Rocky Point. To get to Puerto Penasco, we cross the Sonoran Desert, which has numerous volcanic rocks and volcanoes; this image taken at the international border in 1979, shows some of the mountains in the southern B&R (probably Precambrian basement rocks).

When we arrive at the northern end of the Sea of Cortez, we find a range of geological features formed by the Colorado River, tidal currents, seasonal southerly winds, and alongshore transport at the coast by combined tidal, wind, and wave-forced flow. The image below shows the CO River to the NW and several Metamorphic Core Complexes (MCCs) and other basement rocks that were created as part of the B&R event. The Sierra Madre Occidental is an extensive mountain range to the southeast with elevations of <5000 feet.

Rocky Pt. is an alternate (colloquial American) name for the town of Puerto Penasco. This region has been explored for a variety of minerals, especially evaporates like borates.

The town of El Golfo de Santa Clara is located at the mouth of the CO River. This is also a favorite resort area, which is near a field of large sand dunes at the coast. It will be discussed in the next couple of posts.

This close-up shows Cholla Hill, where thousands of Americans congregate every Easter and enjoy a wide range of water and land activities, including offroading.

The top of Cholla Hill is ~330 feet but it is located directly on the coast. Cholla Hill is an outlier of the B&R with pC granite and metamorphic rocks visible at the top. There is also a breathtaking view of the coast. The first image is looking to the NW towards the CO River. The degree of erosion of this quartz-rich (granite/metamorphic) rock is evident in the sandy ramp that leads almost to its peak, which is a favorite sand racing spot.

The image below is to the SE, with Puerto Penasco in the distance.

And a short jaunt takes us to the shore, where we can run down the beach in sand or sea…

This is a major spot today for U.S. holidays. The beach is very sandy at this location and the tides are not too large. We have a very different story in the next posts.

Recent Comments