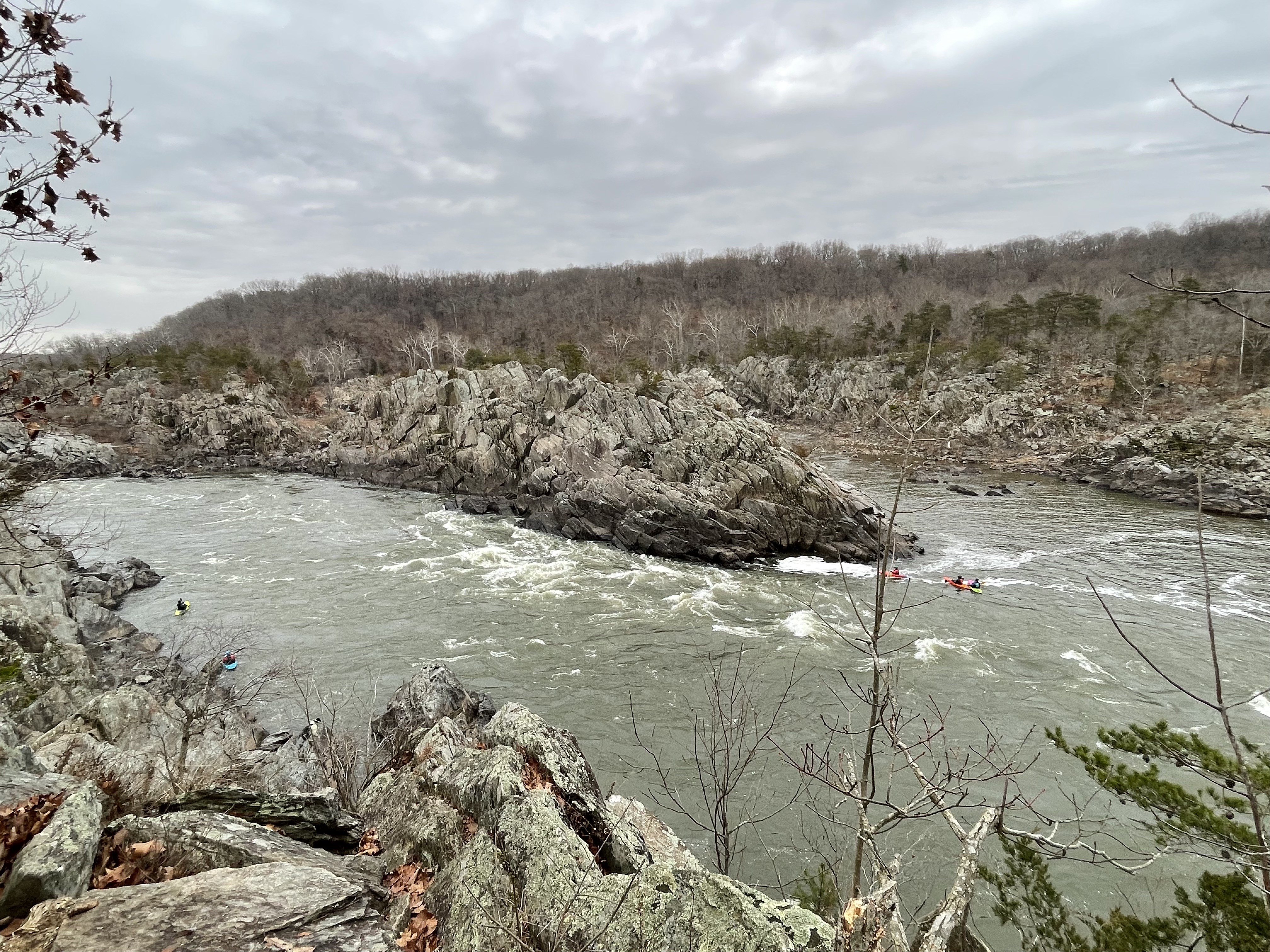

New Year’s Day at Mather Gorge

Figure 1. View of Great Falls, Virginia, from the observation platform. If you look closely, you will see a contact between slightly lighter rocks to the left on the central island, and darker rocks to the right (the contact is just above the white water in the center of the photo). The lighter rocks are schist (originally mud) and the darker ones are metagraywacke (originally muddy sandstone with rock fragments) that were deposited continuously and metamorphosed about 1000 to 511 Ma. The image is looking north from the location shown by a star in Fig. 2. The muddy sandstone (i.e. metagraywacke) is older. We saw these rocks further downstream in a previous post. The transition from coarser to finer grained sediments suggests that an elevated region (e.g. mountains) was worn down over tens of millions of years.

Figure 2. Geologic map of Mather Gorge. The contact between the (originally) muddy sediment and coarser graywacke is shown by the dotted line. The star is located approximately. We examined the schist exposed at the observation area in a previous post. The area within the rectangle had many exposures of weathered metamorphic rock that was locally schist or metagraywacke. There is no unconformity in this area, so these rocks represent continuous deposition; thus, the metamorphosed sediments vary a lot between these two facies. We followed the river trail (white, dashed line closest to the Potomac River) south. The blue-gray line pointing NW from the Potomac is the old canal and not a modern stream, although there are several steep ravines leading to the river along Mather Gorge.

Figure 3. View looking upstream of a ravine leading to the Potomac. The waterfall is about 200 yards away and drops about 20 feet. The rocks are very thick bedded and steeply dipping to the WNW in this area, but their dip varies widely because of past tectonic deformation.

Figure 4. View looking downstream from the same location as in Fig. 3. The Potomac River can be seen in the upper center of the photo as a gray triangle pointing downward. Note the large blocks of metagraywacke clogging the channel and the steep face on the other side of the river. A nearby ravine like this was used to construct a series of locks to raise barges about 80 feet to enter an 18th century canal system (see Fig. 2 for location).

Figure 5. Bedding surface of metagraywacke, showing preserved bed forms suggestive of slumping. The raised surfaces are elongate ovals that indicate an original flow direction aligned with vertical in this photo’s orientation.

Figure 6. Close-up image (4x magnification) perpendicular to a bedding plane like that shown in Fig. 4. Thin bedding was deformed during burial by quartz inclusions (light colored, massive areas), which formed from silica squeezed out of clay layers containing a lot of water. The original muddy sediment was buried rapidly, trapping excess water within it. This sample doesn’t have sand or rock fragments visible at this magnification. The slightly golden area to the left of the center looked like pyrite (an iron sulfide mineral) but that’s just speculation; however, it is consistent with muddy sediment containing organic material.

Figure 7. This photograph reveals how plants speed up the weathering of rocks. The roots of this tree split the rock along weak planes, allowing water to penetrate and chemically breakdown the platy, micaceous minerals comprising schist.

The schists and metagraywackes we’ve seen exposed along more than ten miles of the Potomac River range from nearly horizontal to tilted almost vertical; in other words, this continuous sedimentary sequence is probably more than a mile thick. They were originally deposited in ocean trenches near a source such as volcanic islands (e.g. Japan), probably during subduction of ocean crust. Over tens of millions of years, volcanism ceased and the mountains eroded to produce massive volumes of mud. Thousands of feet of additional sediment (now eroded) would have buried these rocks deeply enough to recrystallize into more suitable mineral assemblages for the high pressure and temperature conditions of a subduction zone.

Before I speculate any further, I should address the steep and irregular angles at which we find these rocks today. This faulting is the result of extension within this area about 200 million years ago, during the breakup of a supercontinent called Pangea. Faulting is a brittle deformation process, which means that the rocks were not buried deeply at the time — a couple of miles, maybe.

Ignoring their steep angles, I haven’t seen evidence of folds in these rocks during my previous surveys in this area, which I find confusing, as an amateur field geologist. Radiometric dating suggests that they were metamorphosed between one billion and 500 million years ago; they were deposited tens of millions of years earlier so the radiometric age spans both deposition and metamorphosis. I don’t understand how sedimentary rocks were changed into metamorphic rocks in what was “obviously” a compressional tectonic regime (i.e. subduction of ocean crust), yet don’t show evidence of small-scale folding, a ductile process that occurs miles beneath the surface. Rocks of the Franciscan Complex (age 150 – 66 Ma) of Northern California, for example, are folded on scales of several feet; I guess these (unnamed) rocks of NOVA had such features erased during their (apparently) deeper burial, not to mention old age (1000 – 500 Ma) …

My confusing becomes vexing when I consider that these (now) metamorphic rocks weren’t deformed (i.e. folded) during the the plate-tectonic collision that created Pangea, a supercontinent assembled about 350 million-years ago. Geologists have long been disoriented by apparent contradictions like this, and they found a solution, which I alluded to in posts from Bull Run Nature Preserve and Shenandoah National Park.

This thick sequence of metasedimentary rocks must have formed part of an overthrust sheet, sliding between other layers of rocks, during the titanic collision that created Pangea. They were pushed far enough to the west that they weren’t assimilated by the Himalayan-scale mountain range that once ran the length of North America’s east coast. They were simply reburied by its sediments, but not deeply enough for their mineral composition to adjust; in other words, they had already seen the worst of their lifetime.

That’s my story … for now.

3 responses to “New Year’s Day at Mather Gorge”

Trackbacks / Pingbacks

- - March 21, 2024

- - August 17, 2024

Hi Mr. Keen. Here’s a photo I took across the river in Maryland along the C&O canal. It shows the folding missing on the Virginia side. When the river level is extremely low, you can see amazing geologic structures at the bottom of Billy Goat Trail. 📸 Look at this post on Facebook https://www.facebook.com/share/4dNvo1zD3tnESsKz/?mibextid=K35XfP

LikeLike