Road Trip Across the U.S.A.

This post is being written in Portland, Oregon, 2800 miles from Northern Virginia, where this journey began. I’m working on an iPad, which is new to me, so I’m going to limit this to a summary of previous posts, and briefly discuss some rocks I haven’t discussed before. I’ll go into more detail on the return trip, which will, however, take a different path.

I have said a lot about the rocks in NOVA (Northern Virginia), so I’ll refer to those posts. The eastern end of Fig. 1 is underlain by rocks more than one billion years old that record a collision on a continental scale.

We also found evidence of deposition in marine and coastal settings throughout the Paleozoic (~500 to 250 my), which I’ve discussed before. This period of erosion was interrupted in the Triassic Period, about 200 my ago, when the east coast began to stretch; coarse sediments filled newly developing basins throughout NOVA.

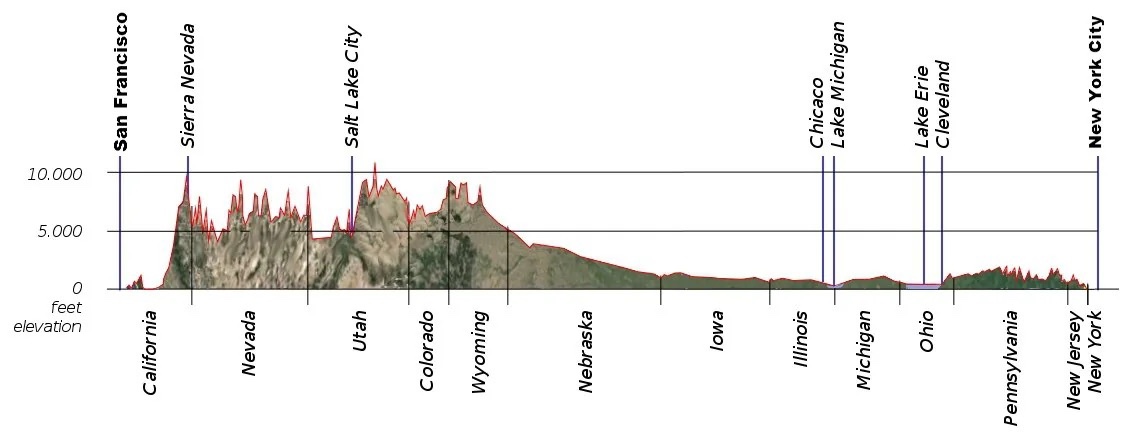

Our westward journey took us through Maryland and Pennsylvania (see profile above), where we found evidence of broad, shallow seas to the west and rising highlands to the east throughout the Paleozoic.

West of the ancestral Appalachian mountains, from Ohio to Illinois, we saw rolling hills covered with farms that replaced primordial forests. I don’t have any photos of this area, but there isn’t much to see. However, this is where extensive glaciation becomes evident, continuing across the Great Plains to Nebraska. I wrote about the moraines that dominate this region in a previous post.

This post picks up the story in eastern Wyoming (see profile above), where we find sediments deposited in coastal areas during the Late Cretaceous (~100 my) dominating the region.

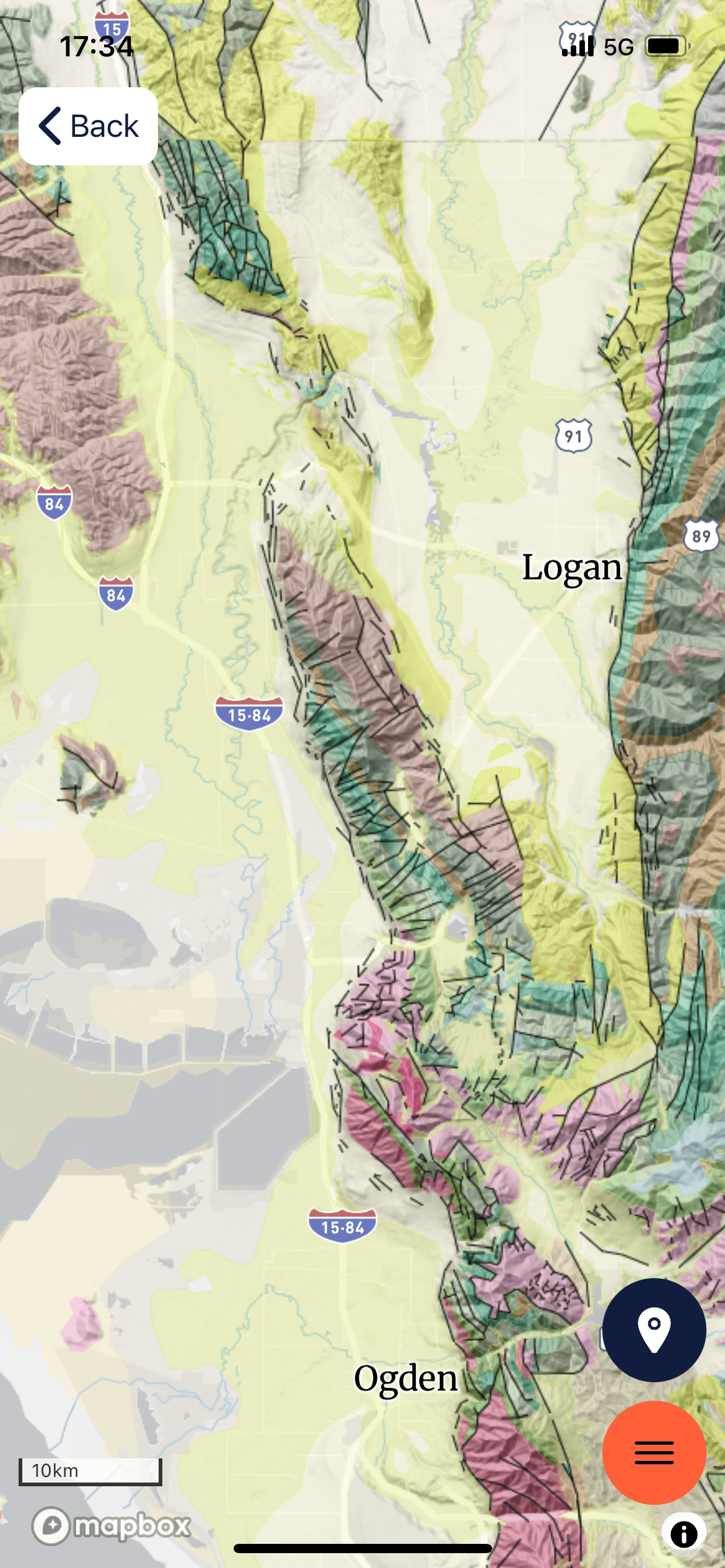

Figure 2. Geologic map of the area around Rawlins, Wyoming. The majority of the rocks (green hues) are Cretaceous (~145-65 my). Faults (black lines) separate these older nearshore sands and muds from Miocene (~20 my) coarse sediments (yellow colors), Paleozoic marine sediments (aqua tints), and Mesozoic nearshore sediments (blue hues). Note the arch form of the Mesozoic layers; this is an anticline, folded layers of rock, the result of crustal shortening (i.e. compression).

SUMMARY. We started out in NOVA, where a titanic collision occurred more than 500 million years ago. We saw evidence of a similar orogeny in the Precambrian rocks exposed in Utah, Wyoming, and Idaho, long before they were deformed and pushed eastward.

During the Paleozoic era (500 – 230 my), thick layers of sediments were deposited in Pennsylvania (see Fig. 1) as the ancestral Appalachian Mountains rose, then eroded over hundreds of millions of years. The proto-Atlantic Ocean (Iapetus) opened and closed during this immense span of time.

We saw similar Paleozoic sedimentary rocks in Utah and Idaho (no photos available) but the big picture of continuous deposition along huge swaths of what is today western North America is recorded elsewhere (e.g. the Grand Canyon and Colorado Plateau).

The Mesozoic era is mostly recorded in sediments associated with the break-up of Pangea in NOVA, where stretching of the crust produced ridges and intervening grabens filled with coarse sediment. The Mesozoic and Cenozoic eras were spent eroding the ancestral Appalachian mountains as Eurasia and North America went their separate ways.

Vast expanses of shallow marine and lacustrine sediments were deposited in the (modern) central and western United States during the Mesozoic, accompanied by the eastward push of older rocks by episodic collisions; this was not a continental collision but probably a series of micro continents and island arcs being absorbed as oceanic crust was subducted. A vast interior seaway reached from the Gulf of Mexico to the Arctic Circle at this time.

The Cenozoic saw the eruption of vast quantities of volcanic material in Oregon and Idaho as Mt. Hood (and other volcanic centers) reached its peak of activity. The Cretaceous seaway dried up and terrestrial sediments replaced marine deposits, as the Colorado Plateau rose more than 5000 feet, shedding sediments everywhere. Finally, great ice sheets carved the earth’s surface into a new landscape defined by moraines and glacial valleys.

The Cenozoic is mostly under represented in NOVA because sediment collected on the continental shelf of North America, which was (and still is) a passive margin. Everything that was carried westward by the Mississippi River system was deposited ultimately in the Gulf of Mexico, where huge oil and gas fields developed from organic material transported by an ancestral Mississippi River drainage system. There was no room for sediment as the Appalachian mountains rose, in response to the removal of miles of overlying rock.

This has been a brief and probably inaccurate comparison and contrast of eastern and western geology of the United States, but it is only what I’ve seen with my own eyes, enhanced by the vast knowledge accumulated by generations of geologists tying the story together.

We’ll see what I learn on the return journey …

Recent Comments