The View from Maryland

Figure 1. This post describes the geology along a short hike along the Appalachian trail (see Fig. 2) to the top of Weverton Cliff, in Maryland. This photo is looking west from the top, towards Harpers Ferry, West Virginia . The Potomac River runs below Weverton Cliff and through the pass in the distance.

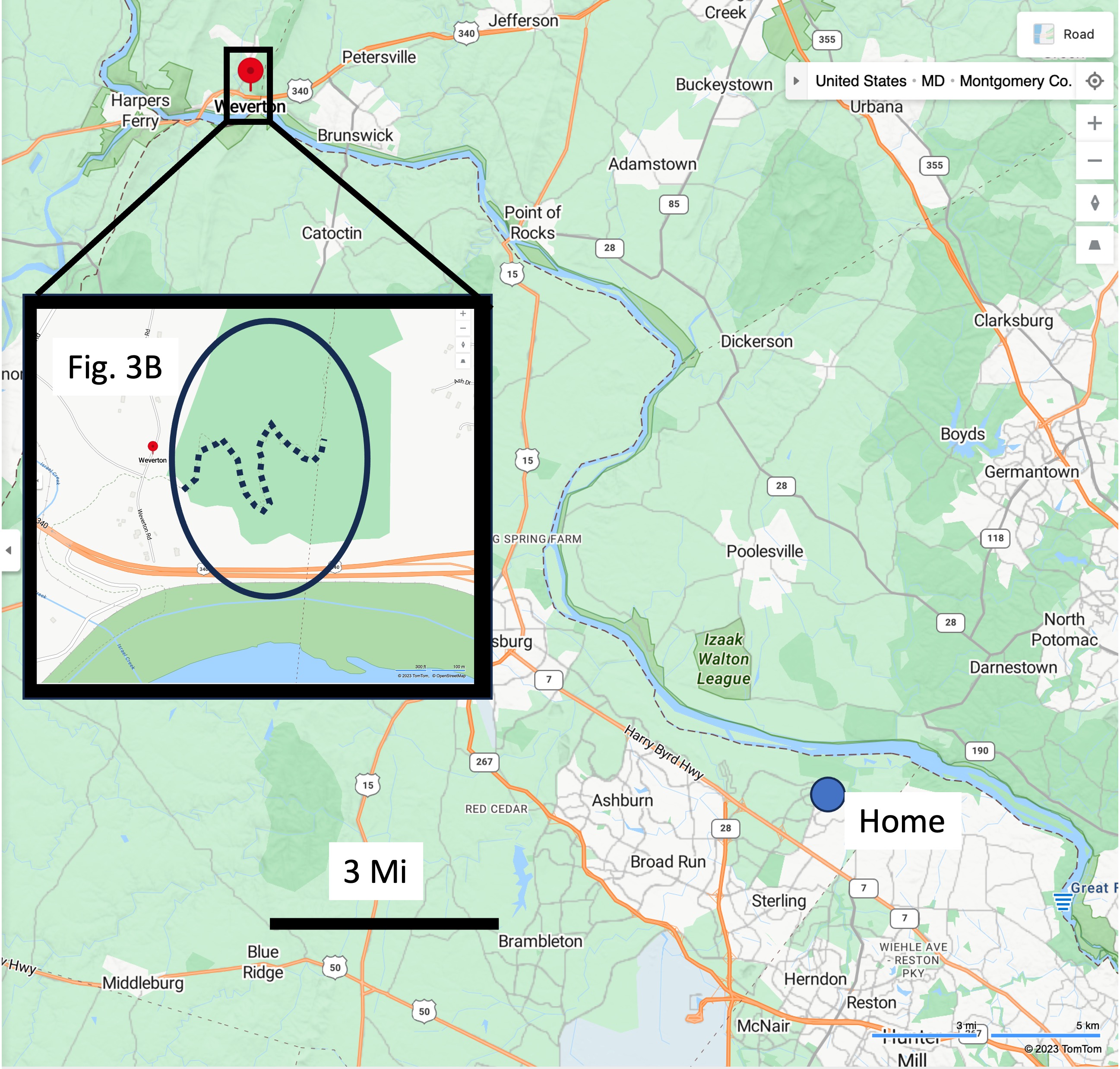

Figure 2. The study area is located on the Maryland side of the Potomac River near the border with West Virginia (inset map), only a few miles as the crow flies from my home in Sterling. The trail climbs the ridge through a series of switchbacks (dotted line in inset map).

Figure 3. Geologic maps of the study area. (A) This larger scale image shows the structural trend common to this part of the Appalachian orogenic belt. The green colors are Paleozoic metasedimentary rocks, which hold up better to erosion than Precambrian metavolcanic rocks (pink shades). (B) The Appalachian trail (dotted line) traverses Proterozoic rocks before crossing a normal fault (dashed line), and encountering Cambrian schist and metasedimentary rocks (Ch and Cw). The rocks are oriented with approximate strike (long line of T-shape at upper center) of 30 degrees east of north; and a dip (short line segment) to the SE of about 45 degrees.

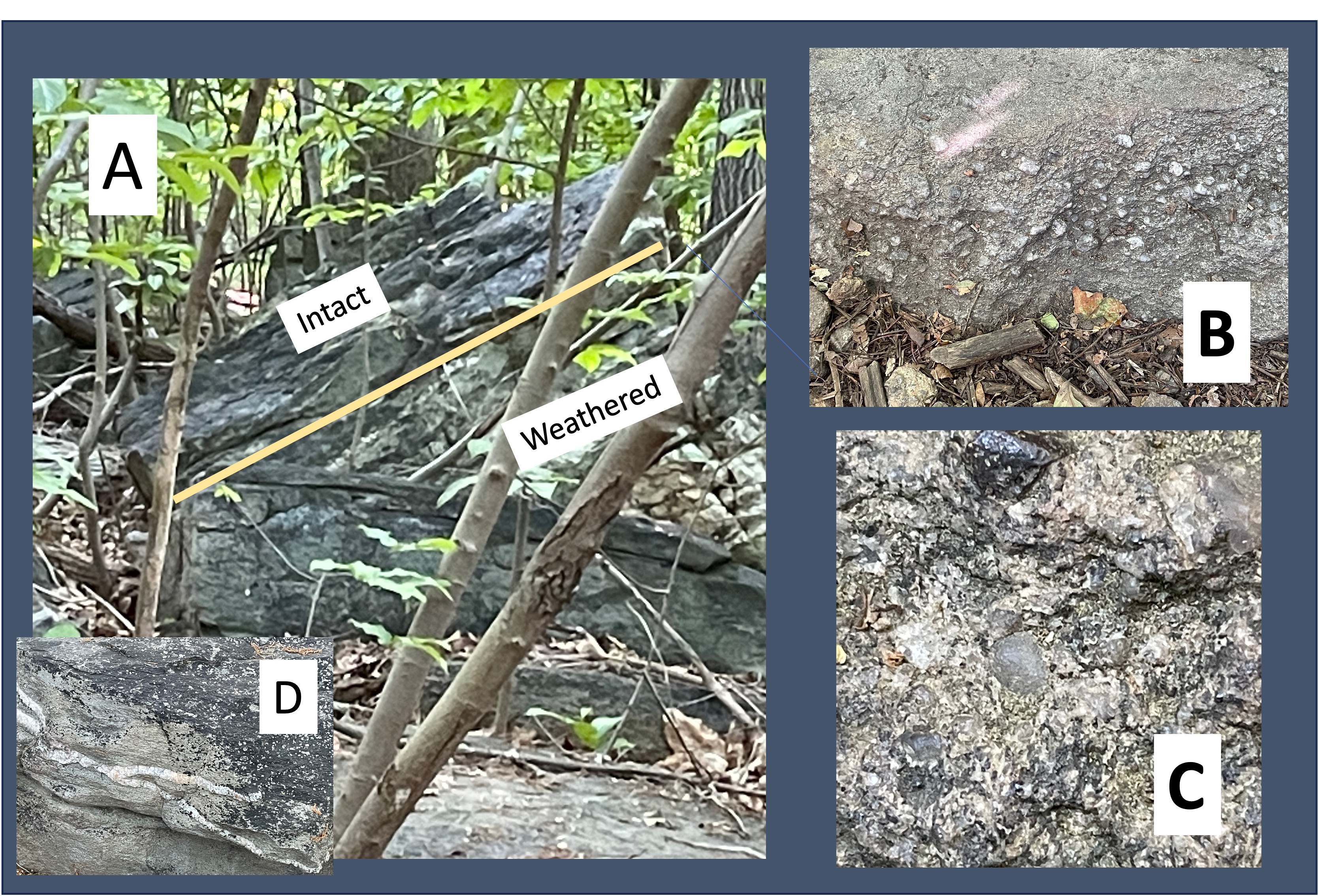

Figure 4. Images of the Harpers Formation taken at site 1 (see Fig. 3B for location). (A) Outcrop showing highly weathered schist at the bottom of the tilted section, similar to what we saw at Bull Run Nature Preserve. The rocks above are relatively intact but show fissility typical of metamorphosed sediments with a relatively high clay content. (B) Close-up of a loose boulder of conglomerate. Note the concentration of larger particles within a layer, with finer grains above and below. This suggests episodic high-flow transport events that transported gravel (there weren’t any land plants to reduce erosion 538 million years ago, when these sediments were originally deposited). (C) Image at 5X magnification of some of the larger grains: the gray is quartz; the irregularly colored clasts are rock fragments; and the dark one at the top may be a metamorphic mineral like garnet. (D) Light-colored minerals like quartz fill fractures and joints throughout the study area, especially within the Harpers Formation. This implies that the sediments had been buried and lithified, then uplifted; jointing occurs during stress relief, like mud cracks; then magma intruded the area and injected liquid (not thick magma) into every available crack.

Figure 5. Photos of Weverton Formation at Site 2 (see Fig. 3B for location): (A) The total exposed section is at least 100 feet thick, comprising mostly sandstone and siltstone with thin layers of shale (identified by being eroded to look like soil). Note the steep dip of the bedding. (B) Conglomerate similar to the Harpers Formation, but with a larger range of sizes, and less matrix. (C) Close-up (5X magnification) of the sandy matrix; the poorly sorted nature of the sediment is evident in the finer sizes, including silt and sand, as well as (originally) clay; this range of particle sizes produced the irregular surface seen in this photo. (D) The exposure at Site 3 shows original bedding warped during burial and deformation; the sediment layers were squeezed like a sponge and produced the lenticular bedding seen in this image.

Figure 6. The bed of the Potomac River reveals resistant layers, which produce the rocky sections seen in this photo taken from Site 3 (top of Weverton cliff).

We saw the Harpers and Weverton Formations before but this is the best exposure so far, which isn’t surprising because the Weverton Formation was named after this location. Let’s see what this field trip adds to what we already learned about the geologic history of the tri-state area (VA-WV-MD).

The proto-North American and Europe plates were moving towards each other during the Proterozoic (~2.5 by to 540 my ago), closing the Iapetus Ocean and smashing any intervening islands onto their margins. Metavolcanic rocks (pink in Fig. 3) were produced during this time, spewed into submarine trenches or along continental margins. Vast quantities of clay were deposited in shallow seas as the continents converged, deposited as the Harpers Formation. The conglomerate of the upper Harpers and Weverton Formations were deposited from rapidly rising mountains and deposited on top of these much older rocks, which may have been exposed to erosion during the millions of years this process required. More sediments were deposited on top of these, burying them as much as ten miles, as the continents continued to collide.

Then … silence … the resulting mountain range stopped rising and began to erode; the sediments had become rock and they fractured, producing joints like we see in Fig. 4D. However, the magma produced by this titanic collision hadn’t cooled, and the joints were filled with hot fluids that flowed into every nook and cranny.

The transition from a collisional margin to an extensional one lasted from 538 my to 200 my ago (that’s 338 my!), at which time Pangea was torn apart by irresistible mantle convection. That is when these rocks were tilted along a series of faults like the Bull Run fault, as they slid into grabens produced by the stretching crust.

My next post will be from Ireland where we’ll see what the rocks tell us from the other side of the still-widening Atlantic Ocean …

Trackbacks / Pingbacks