Deception Pass: Ophiolite or Volcaniclastic Sediments?

Now that I have a general idea of the geologic history of Northwest Washington (NWA) it’s time to start filling in the blanks. I immediately found a discrepancy in the rocks found on the northern end of Whidbey Island and the adjacent peninsula (Fig. 1): some authors identified these rocks as ophiolite–pieces of ocean crust that contain evidence of extrusion at mid-ocean ridges. Let’s see what I found.

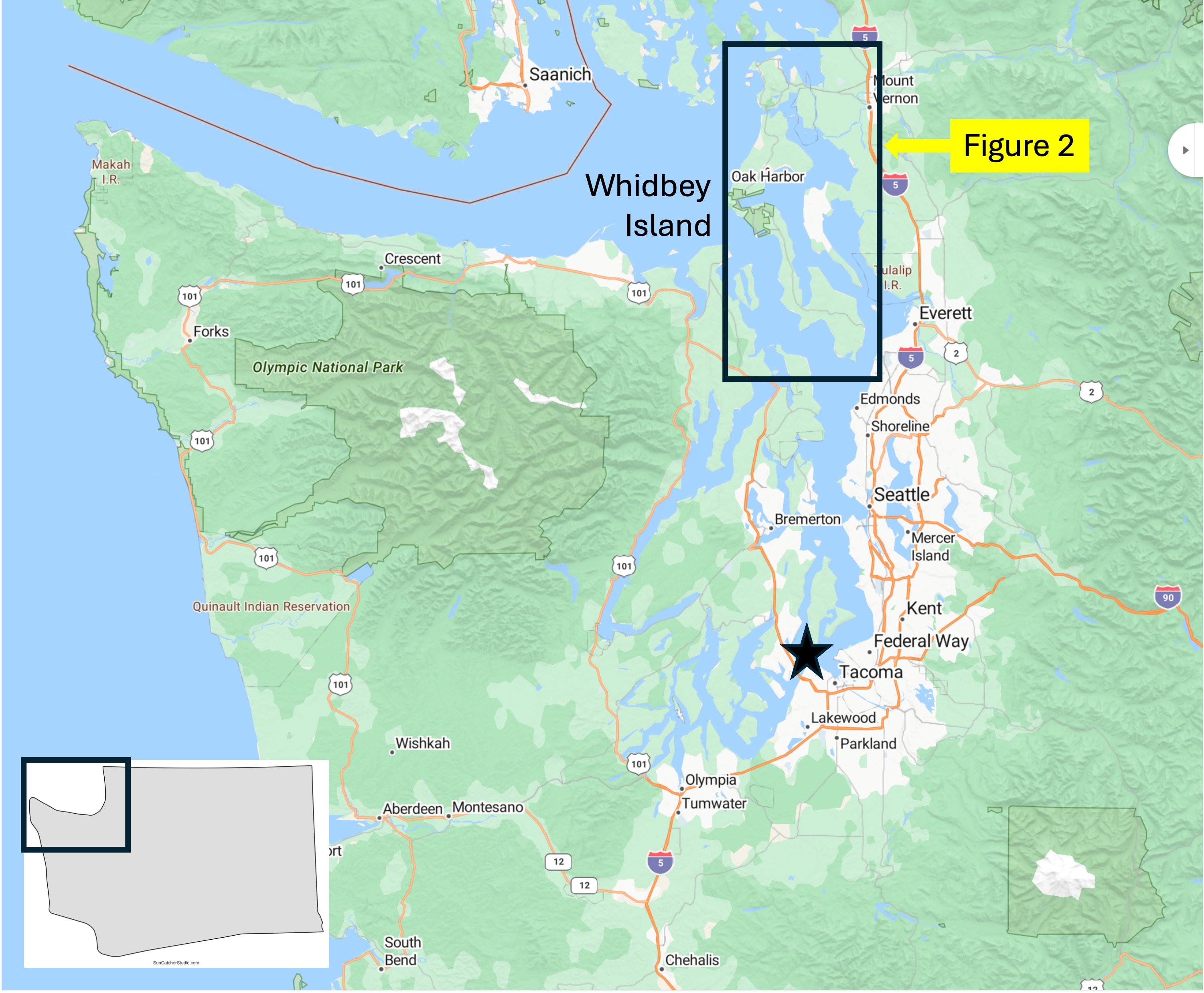

Figure 1. Whidbey Island is a large island that is almost completely covered by glacial sediments. Its elevation varies from less than 100 feet above msl (mean sea level) to almost 400 feet, probably reflecting the presence of terminal morraines deposited as glaciers retreated. The box encompasses the study area, and the star is my home in Tacoma.

Figure 2. Progressively more detailed maps of Whidbey Island, showing the geological formations discussed in this post. (A) Deception Pass is a narrow channel (~200 yards wide) between Whidbey Island and a tiny island that connects it to a peninsula. Glaciers covered this entire area, advancing and retreating for at least two million years, while scraping out Puget Sound from unconsolidated sediments and easily eroded rocks. I entered Whidbey Island via a ferry from the mainland just north of Seattle. (B) Geologic map of the norther tip of Whidbey Island and the adjacent peninsula. The tan areas are covered by glacial sediments whereas the blue and green areas are reported as volcaniclastic rocks by Rock-D and the US Geological Survey national map. However, I read a Washington State geological report from 1962 that reported layered gabbro and other indices of a classic ophiolite sequence. Were Washington’s geologists incompetent? Over eager? Non-peer-reviewed? Or maybe they stumbled onto an exposure, described it in a state report, and, when no one cared, dropped it until they retired. I don’t know. Nevertheless, everyone is in agreement that the age of these rocks, which include basalt and marine sediments, is poorly constrained: they could be as old as 251 Ma, the beginning of the Mesozoic era; and as young as 66 Ma–the end of the Mesozoic. Wow! The thin, black lines indicate faults inferred from stratigraphic relations. The USGS has adopted the generally accepted paradigm of gathering legacy geological formations into larger groups that reflect the plate tectonic setting, rather than geographic location. The “official” description is so encompassing (including the kitchen sink) that it could easily include what the Washington geologic report called “ophiolite”. (C) Detailed map showing my approximate location along the path that followed the shoreline (blue circle) and the location where I saw these rocks in an excellent exposure (yellow diamond). I’m not sure why the rocks south of Deception Pass (blue) are differentiated from those on the north side (green) by Rock-D; the USGS map shows they are the same, as does my field examination (discussed below).

Figure 3. The ferry ride from Mulkiteo to Whidbey Island (see Fig. 2A) shows the same high elevation of Whidbey Island (left), Hat Island (center), and a promontory north of Tulalip (behind the ferry; see Fig. 1). This elevation of glacial sediments is approximately the same as the basement rock discussed below. This high relief shoreline is found throughout Puget Sound.

Figure 4. View looking north across Deception Pass, showing the nearly vertical bedding of rock layers, which could be original sedimentary fabric, metamorphic surfaces, or joints. Let’s have a closer look.

Figure 5. Images of the exposed rocks near the top of the hill overlooking Deception Pass (see Fig. 2C for location). (A) These medium bedded (~6 inches) layers contain clasts of different rocks. The height of the image is about six feet. (B) This twelve-foot exposure shows thin-bedded sand/silt layers with intercalated mud, but the layers are overturned (more than 90 degrees from horizontal) and reveal rapid changes in bedding, in addition to large boulders of material. (C) A bedding surface shows the characteristic sheen of schist, which adds metamorphic foliation to original bedding. These rocks are not heavily altered, so the layers seen in (B) probably reflect original beds. The clasts in (A) are matrix supported, which suggests mixing of different sized particles. This unusual texture occurs in environments where periodic mass failures (e.g. landslides or submarine slides) occur.

Figure 6. These images from about 100 feet elevation show more details of the rocks exposed at Deception Pass: (A) These layered sediments vary from medium to thick bedded and they also reveal gentle folding at this scale (the photo is ten feet high), suggesting that the overturned beds may be part of a large fold, possibly related to the faults seen in Figs. 2 B and C; note that the faults have a NW-SE orientation approximately aligned with the fold axis (I didn’t make careful measurements). It is also possible that the faults reflect brittle failure as the rocks were uplifted within the accretionary prism. (B) The left half of the exposure reveals a thick (> four feet) layer containing mixed clasts in an otherwise fine-grained matrix. The right side contains medium beds of a lighter material (We don’t want to get carried away here because of the vagaries of chemical weathering.) However, the contact between the two apparent lithologies is irregular; If I’m right about the left side being the bottom (questionable), this could have been a volcaniclastic slide (basalt, ash, pieces of rock, etc) that was then filled in by less catastrophic sedimentation. I admit I’m speculating, but we have to imagine life on the continental margin during active volcanism, during subduction.

Figure 7. This photo was taken looking west from Deception Pass (see Fig. 1), towards the Pacific Ocean. Those islands are emergent blocks of jumbled Mesozoic/Tertiary sedimentary and volcanic rocks. The last ten-thousand years of sea level rise has covered most of the evidence contained within the accretionary prism, leaving us with only fragments.

Conclusion. I didn’t see any ophiolite at Deception Pass, but there is plenty of evidence of accretionary tectonics; deeply buried sediments and volcanics were scraped off the subducting oceanic crust and deformed continuously. This process has to obey the laws of conservation of mass, which means that the accretionary prism accumulates further west with each passing year. What we see exposed at the northern end of Whidbey Island is occurring today beneath the continental shelf, all while the Juan de Fuca plate is swallowed by the earth’s mantle. There is a two-mile-deep trench about 100 miles off NWA, but it is filled with sediment eroded from N. America, unlike more-familiar deep-sea trenches (e.g. the Mariana Trench, about 7 miles deep).

All that sediment in the subduction trench is like sand in in your transmission: it gums up the works and slows things down, but the Earth cannot be stopped, its relentless, insatiable appetite for oceanic crust never satisfied. It will keep chewing up the Juan de Fuca plate until the upper mantle decides that enough is enough and stops pushing N America westward.

I can’t wait to see how this ends…

Recent Comments