The Chesapeake and Ohio Canal at Fletchers Cove: Same ol’ Same ol’

Figure 1. View looking upstream (NW) at Fletchers Cove (see Fig. 2 for location). The park occupies a floodplain opposite cliffs, seen rising to the left in the photo. The water level and flow were high after a tropical depression, but the river bottom isn’t rocky in this relatively deep pool.

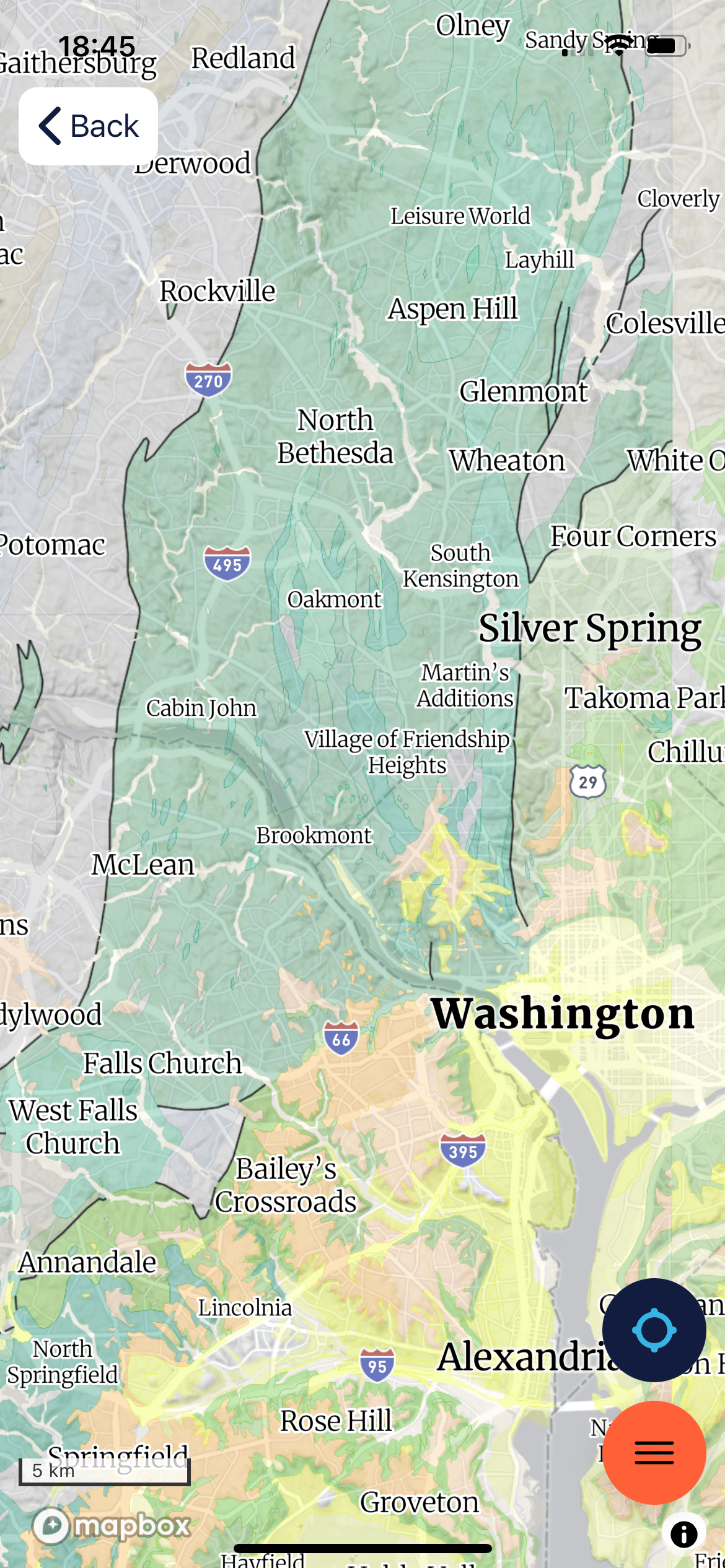

Figure 2. Map of the Potomac River, from Mather Gorge (yellow circle) to Washington DC. The inset geologic map (Rock D) shows relatively uniform rocks in this area. The expanse of the river covered in this post extends between the small, blue dots in the inset map. Other sites along the Potomac River have been discussed in previous posts: Mather Gorge; Scotts Run; and Turkey Run Park. This post will discuss how these areas are related geologically. Fletchers Cove is only three miles from the beginning of the Chesapeake and Ohio canal which terminates in Washington DC; this was a successful canal system, established in the nineteenth century, that is now a hiking/biking path to Harpers Ferry, WV.

Figure 3. The C&O canal looking upstream at Fletchers Cove (magenta circle in Fig. 2). This stretch of the Potomac River lies between locks, i.e., the C&O canal is nearly horizontal, to make upstream trips easier in its heyday (nineteenth century) when horses/mules or oxen pulled the barges.

Figure 4. There were no exposed rocks accessible, but many large boulders were used in the parking area at Fletchers Cove. This is a typical example of Sykesville Formation rocks (~538-470 Ma) at Fletchers Cove. Rock D reports this as conglomerate or diamictite, which has been metamorphosed and folded. This sample contains abundant fine-grained, brown matrix material with light-colored intercalated layers; however, no clasts are evident in this boulder. The lighter layers form lenses (lower-center of photo) and boudins (sausage-like layers in the middle of photo); these bedding types are associated with isostatic pressure squeezing sediment layers with different compositions. The Sykesville Fm is 3000 m thick and tilted about 30 degrees to the SE; thus, the oldest (and deepest buried) rocks are at Fletchers Cove. I’ll discuss this further below. I would like to add that the light layers in this sample lack the luster and conchoidal fracture that are characteristic of quartz. The difference in color could be caused by chemical diffusion during burial.

Figure 5. Photo looking upstream at the Chain Bridge (small blue dot with halo in Fig. 2 inset). With the high water level when I visited, the rocky bottom at this location formed dangerous rapids. Note the bluff on the western bank. There is no change in lithology across the Potomac River here (see inset of Fig. 2) and there are no known faults; the river simply eroded through any weakness in the rock.

Figure 6. Sykesville Formation metasediments (538 – 511 Ma) at Turkey Run Park (red circle in Fig. 2). This bedding surface is consistent with slumping of fine-grained sediments on a steep ocean floor (e.g. an ocean trench near a subduction zone). Turkey Run is ~4 miles (6.5 km) from Fletchers Cove; a back-of-the-envelope estimate of the stratigraphic (i.e. perpendicular to original horizontal) distance between these “exposures” is 3.2 km. The reported thickness of the Sykesville Fm is 3 km; this implies that Fletchers Cove is near the bottom of this pile of metasediments, and Turkey Run is near the top. I’ll discuss this below. The rocks at Turkey Run have very similar bedding to Fig. 4 above, but with more quartz because they were intruded by magma (488-423 Ma) and quartz veins followed bedding and filled joints. It is worth noting that Fig. 6 was originally 3000 m higher within these sediments than Fig. 4, and 5.8 km distant on the original surface. A few quartz veins were observed along fractures at Fletchers Cove, probably associated with the intrusion observed at Turkey Run.

Figure 7. Proterozoic (1000 – 511 Ma) metasediments at Scotts Run Park. The rocks exposed here (green circle in Fig. 2) includes metagraywacke (poorly sorted sandstone) and schist (metamorphosed shale). There is a major, NW fault less than a km east of Scotts Run Park. Normal faults lift older rocks from deeper within the earth’s crust and expose them alongside younger strata. Along the Potomac River, this creates a younger sequence of sediments (Fletchers Cove to Turkey Run) apparently overlain by the older rocks at Scotts Run. I should add that the normal fault interpretation is not the only one; low-angle, thrust faults (AKA overthrust faults) can push older rocks over younger, for many kilometers. (More about this later.)

Figure 8. Precambrian metagraywacke (1000 – 511 Ma) bedding plane at Mather Gorge (yellow circle in Fig. 2). These rocks have the same age as those at Scotts Run (green circle in Fig. 2); they are also very similar in lithology to the younger rocks at Turkey Run and Fletchers Cove. What is significant about this photo is that it reveals surface features indicative of slumping; these bed forms represent muddy sediment sliding along a steep seafloor episodically. Similar bed forms are evident on the bedding plane from a boulder at Fletchers Cove (Fig. 4).

Figure 9. Geologic map of the Potomac River area. The green area is Sykesville Formation metasedimentary rocks, metamorphosed between 538 and 511 Ma; a younger limit of 470 Ma reported for Fletchers Cove could be anomalous because of emplacement of intrusive rocks at Turkey Run about that time. Also, metamorphism is not simultaneous throughout an area this large. This is a continuous sequence ~3000 m thick. The mauve area to the west represents the older metasediments seen at Scotts Run and Mather Gorge. Note the mauve area west of Bailey’s Crossroads; this is bounded by faults on three sides, which isn’t consistent with normal faulting as discussed above. The discrepancy in ages between the stratigraphically higher, yet older metasediments (1000 Ma) and Sykesville Fm rocks (538 Ma), in combination with this outlier, suggests that the older rocks slid over the younger rocks along a thrust fault. These result from compressional rather than extensional tectonic forces. We have seen evidence of overthrust faults in a previous post.

SUMMARY. The rocks tell a simple story of continuous deposition of immature sediments (e.g. graywacke and diamictite) between 1000 and 500 million years ago. This long period was terminated by intrusion of tonalite into these deeply buried sediments about 470 Ma. At some point during this time the older rocks were pushed over the younger Sykesville Fm during a compressional tectonic event.

A predecessor to the Atlantic Ocean, between 600 and 400 my, has been proposed to explain construction of the supercontinent Pangaea. This hypothesized ocean is called Iapetus. It had disappeared by 400 my.

The metasediments of the Sykesville Fm (538-511 Ma) fit nicely with subduction of Iapetus’ oceanic crust; the intrusive rocks (470 Ma) are also nicely contained in this timeline. The oldest metamorphic rocks we’ve examined precede Iapetus by 400 my, even though they have similar lithologies (and presumably origins) as the Sykesville Fm. At this point, some speculation is required.

The Iapetus Ocean opened after a lengthy orogenic period (1250 – 980 Ma) referred to as the Grenville Orogeny, and it closed between ~600 and 400 my, forming Laurasia and Pangaea. The continuous deposition of poorly sorted marine sediments for 500 my suggests to me that an ocean basin was being subducted (similar to the Western Pacific today, which has been sliding beneath Asia for 200 my). This probably included island arcs like Japan. All of the volcanism was occurring further to the east (in the modern Atlantic Ocean), however; but the sediments eroded from volcanic islands were deposited in a deep-sea trench.

By the time the tonalite was intruded (470 Ma), the sedimentary slab was probably 10 km thick, which is deep enough to create metamorphic rocks. However, something immovable collided with this slab of sediments and pushed the Grenville age rocks (e.g. from Mathers Gorge) over the younger Sykesville Fm strata along weak planes in the sediment pile. This would have been the Acadian Orogeny, which created Pangaea.

These rocks have something less speculative to add: I referred to a regional westerly dip of these metasediments, about 30 degrees with a northeasterly strike. This is caused by a series of normal faults created during the late Triassic (~210 my), when Pangaea was torn apart by what is today the Atlantic Mid-Ocean Ridge.

I’m not going to extrapolate my speculation to the metamorphic rocks exposed at Great Falls, which also have metamorphic ages of 1000 – 511 Ma.

Earth is a wild and crazy planet …

Recent Comments