Turkey Run State Park

Figure 1. View looking upstream in a small creek flowing into the Potomac River (see Fig. 2 for location). The hills are covered with a thin veneer of fine sediment deposited on Proterozoic and Paleozoic (i.e. 585-443 Ma) rocks. This image shows several ledges of this basement rock, which is the topic of this post.

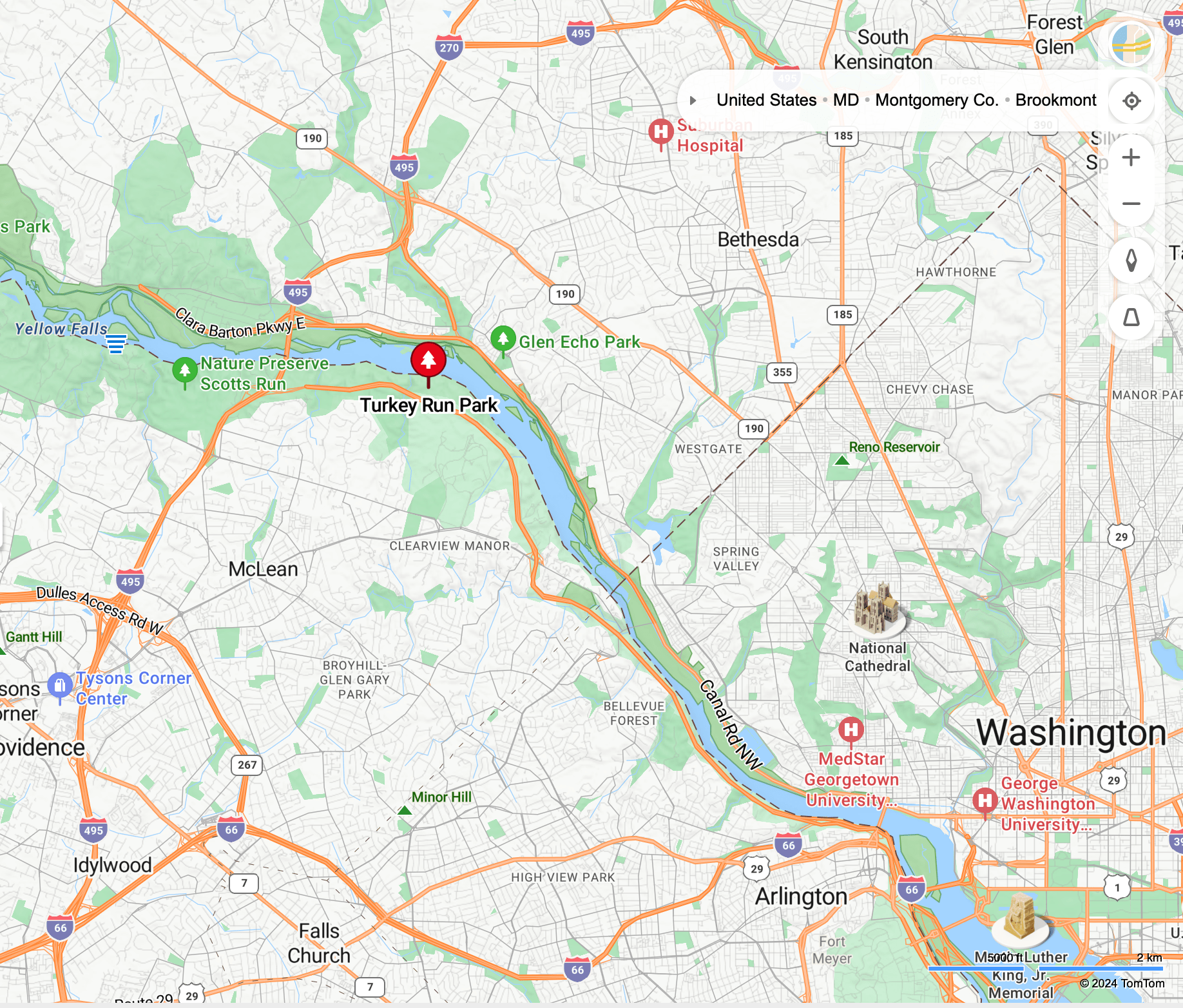

Figure 2. Map showing Turkey Run Park relative to Washington DC. Further upstream, at Scotts Run (labeled on the map), we saw Proterozoic (2500 – 542 Ma) metamorphic rocks.

INTRUSIVE ROCKS

Figure 3. Outcrop of the Ordovician (488-423 Ma) tonalite, a medium-to-coarse-grained intrusive rock. Tonalite contains little or no quartz. This is a typical exposure in this area. This rock doesn’t form cliffs and the river isn’t contained within a narrow gorge as we saw further upstream. Large blocks have fallen away as the low and irregular bluffs erode. We’ll examine this tonalite in closer detail next.

Figure 4. Tonalite exposed further downstream from Fig. 1. Note the veins of light-colored minerals running through the rock. These are veins of quartz that filled fractures in the magma after it had cooled, but was still above quartz’s melting temperature. These veins are irregular because intrusive rocks aren’t layered like sedimentary rocks; they probably also reflect slow deformation of the semisolid magma on geologic time scales (i.e. millions of years).

Figure 5. Close-up of tonalite (image about 2 inches across), showing rectangular feldspar crystals and darker biotite and hornblende, which make up about half the composition. The darker minerals weather faster than the feldspar, leaving the latter protruding from the surface. This image also shows a slight foliation, running from the upper left to lower right. Foliation in igneous rocks can be syndepositional (i.e. as the magma cooled) or created when the solid rock is reheated enough to deform without breaking. I think these rocks fall in the first category.

Figure 6. This unusual image shows a layer of foliated tonalite sandwiched between two blocks that appear undeformed. This is probably an illusion caused by irregular weathering; however, Rock D reports this rock unit as containing fragments of older rock and previously solidified tonalite. The emplacement of a large batholith takes tens-of-millions of years to complete, during which time there was probably considerable crustal shortening associated with collisional plate tectonics. (Honestly, I wish I hadn’t taken this photo because it is really strange …)

Figure 7. Joint surface within the tonalite. Joints form when the magma has solidified and is brittle, tens if not hundreds of millions of years later. These joints were almost perfectly symmetrical, with 90 degrees between intersecting planes. Such an orientation suggests that the stress regime was uniform (horizontally and vertically). In other words, they occurred during uplift (isostatic stress regime) and not during an orogeny, i.e., they occurred a long time (geologically) after the events these rocks record.

METASEDIMENTARY ROCKS

Figure 8. This photo shows the approximate contact between the Ordovician intrusive tonalite and the older, overlying Cambrian (542-488 Ma) metasedimentary rocks (intrusive rocks come from deep within the earth). The boulders lying around are mixed lithologies, representing the two rocks. Whether the stream flowing towards the camera followed the contact (they are often weak points) or not is an open question.

Figure 9. Exposure of the Cambrian Sykesville Formation metasedimentary rocks into which the tonalite was intruded. These rocks were deposited in an ocean floor/deep-sea trench environment millions of years before they were buried deeply and heated enough to be metamorphosed. Their geologic age is uncertain but Rock D reports an age of 497-470 Ma. Considering that they had to be deposited and buried before being metamorphosed, it is reasonable to assume that they were deposited about 540 million-years ago. The tonalite age of 485-443 Ma is on firmer ground because this is an intrusive rock that can be dated by radioactive isotopes trapped in the minerals comprising it. Nevertheless, their ages overlap, which requires some explanation. Such large age ranges reflect the errors associated with dating rocks this old, but also the duration of orogenic events (I’ll get to that later). I tend to trust the oldest age reported because, when radiometric daughter products (used to calculate ages) escape from the rock, the apparent age will only decrease; thus I think the tonalite was intruded sporadically starting about 485 million-years ago. Note that the bedding is tilted to the right, which is to the west; I didn’t measure strike and dip, but the orientation is consistent with regional trends — dipping to the WNW at about 35 degrees.

Figure 10. Original bedding plane of the metasedimentary rocks. The lumpy surface is very similar to muddy sediments in modern submarine fan and trench settings, where sediment slides down steep slopes. Any fossils (if there ever were any) were destroyed during metamorphosis, which contributes to the dating problem I alluded to above.

FIELD RELATIONS

Figure 11. Exposure of the metasediments, showing light-colored layers within the darker beds of these rocks — exemplified by the thin layer just below the tree leaning to the right in the center of the photo (No, I didn’t tilt the camera; the tree is growing like that).

Figure 12. Photo of a block that fell away from the exposure seen in Fig. 11. This is mostly quartz but it contains several elongate fragments of metasedimentary rock. Although tonalite contains very little quartz, the original magma contained enough silica (Quartz is SiO4, pure silica) that magmatic fluids high in silica were infused into the overlying rocks as the magma cooled. Note that the country rock didn’t melt but was broken off during injection.

Figure 13. Exposure of a quartz-rich area within the metasedimentary rock.

Figure 14. Close-up of the exposure in Fig. 13, showing large quartz nodules. The red stains come from oxidation of iron-rich sediments in the country rock. The image is about two-feet across. The magma didn’t contain an abundance of rare-earth elements, but this looks like a pegmatite to me. Pegmatites form from excess quartz and other incompatible elements (e.g. lithium, tantalum, molybdenum) that remain in the last bit of semifluid as the magma cools; thus they are injected into the country rock as veins following weak zones (e.g. Fig. 11) to form large inclusions.

SUMMARY

We saw a lot today. More than 500 million-years ago, muddy sediments were deposited in a deep-sea environment, probably a subduction trench created as the Iapetus Ocean closed. This wasn’t a continental collision but more like we see in modern Japan or the Philippines. These sediments were buried over millions of years, finally heating enough under sufficient pressure to form new minerals but not obliterating their original sedimentary structures. About 485 million-years ago, magma rose from deep within the crust and forced its way into these ductile (but not molten) rocks, forcing high-pressure fluids rich in silicon along bedding planes, breaking off pieces of the older metasedimentary rocks and entraining them.

Today’s walk in the park took us to a time when an ocean basin was being subducted beneath a continent to form a supercontinent called Pangea.

These rocks record the Taconic Orogeny, the first in a series of collisional events that shook porto-north America to its roots. It was followed by continuous mountain building, culminating with the Allegehanian Orogeny, which ended approximately 260 million-years ago.

Radiometric ages tell us that the closing of Iapetus began at least 500 million-years ago and continued for 240 million years. However, the collision of tectonic plates isn’t defined by a single orogeny, as recorded in the rocks when continents are involved. I would like to point out that this massive tectonic event coincides with the evolution of animals, from the first mollusks to complex vertebrates like reptiles.

The evolution of life is closely correlated with plate tectonics so, the next time you see a rock in its natural state, take a moment to appreciate the debt we all owe to the earth …

Trackbacks / Pingbacks