Coast to Coast

Plate 1. We’re not in Northern Virginia anymore!

I’ve relocated to the west coast–Tacoma, Washington to be exact, and that active stratovolcano looming in the background is Mt Rainier (aka Tahoma as it’s known to the indigenous people). The pristine water body is Commencement Bay at the southern end of Puget Sound. Mt Rainier is 14410 feet high, which makes it the most topographically prominent mountain in the lower 48 states; for scale, it is 43 miles from Tacoma, yet dominates the SE horizon. How did it come to be so close to the coast and yet so tall? Before I answer that question, let’s recap the geological story of NoVA that I pieced together over the last four years.

Over a billion years ago, NoVA was submerged beneath an ocean or marginal sea. Distant mountains eroded rapidly in a time before land plants. Vast quantities of sediment accumulated in layers of erosional debris that were subsequently buried by younger sediment. Between a billion and five-hundred million years ago, these sediments became rocks that were subsequently deformed as continental plates collided. They didn’t melt, however, and survived the cataclysm relatively unharmed, becoming schist and related metasedimentary rocks.

Plate 2. This schematic cross-section of the US East Coast is representative of NoVA. It shows the final closing of the Iapetus Ocean (forerunner of the Atlantic), which would have produced immense quantities of terrestrial sediments (e.g. the Devonian Catskill Delta in panel B). Unfortunately, these river and lacustrine sediments were subsequently eroded in NoVa as the ensuing mountains grew in size (panels C through E). They are today preserved in western New York State and eastern Pennsylvania. What survived in NoVA are older metasediments, ranging from ~1200 to 500 Ma, which were buried beneath the material eroded along the western margin of this figure (the yellow areas). Some Devonian intrusive rocks, intruded into older metasediments, survived along the Potomac River.

Plate 3. This reconstruction of the supercontinent, Pangea, coincides with Plate 2E. The square indicates NoVA. Pangea began to crack apart ~210 my ago, split by a spreading tectonic plate boundary, and for the last 200 million years, the older rocks have been slowly working their way to the surface as younger rocks were removed by erosion. They are now exposed to the elements and are weathering to form new layers of sediment in the Atlantic Ocean, beginning a new cycle.

What about the northwest coast, Tacoma and Seattle, you may ask?

Plate 4. This beautiful schematic cross-section represents the consensus opinion of geologists familiar with the Cascadia region. Tacoma lies at the northern end, near Mt Rainier. I will refer to this image frequently in my following posts. Study it a moment and you will realize that the geologic situation is similar to that presented in Plate 2A and B, but on the eastern (right) side of the closing ocean basin, i.e., the Pacific Ocean.

The Coast Range (including Olympic peninsula) is part of the accretionary wedge of a subduction zone, and Puget Sound lies within the forearc basin. In other words, I have moved from an extinct collisional tectonic regime to an active SUBDUCTION zone; Mt Rainier (Plate 1) is the tip of the geological iceberg, leaking sweat from the partially melting Juan de Fuca tectonic plate.

I hope you join me on this new geological adventure into the past…

Geological Cycles at Wolf Trap National Park

Figure 1. (A) Wolf Trap National Park for the Performing Arts is located about twenty miles west of Washington DC, near several parks I’ve discussed in previous posts, especially Great Falls National Monument. The geology of the area is dominated by Neoproterozoic-to-Cambrian (1000 – 511 Ma) metasedimentary rocks that originated in oceanic environments near rapidly rising mountains (e.g., a volcanic island arc). The dates are from the time of metamorphosis, which is why they give such a long time span. Taking into account the accuracy of the dates in general, this region was undergoing erosion with the resultant sediment buried in marine trenches, probably near a subduction zone, for hundreds of millions of years. The majority of the material would have been mud. There would have been hiatuses (perhaps an ocean basin briefly emerged), but such detail is lost to us after so long. (B) This map of Wolf Trap Park shows the trail we followed. The map doesn’t show topography, but the ridges are short, with maximum relief less than 100 feet. Wolf Trap creek enters from the west (left side of panel B) and flows through a wetland area (indicated by blue ellipse) before meandering a little and following the east side of the valley.

Figure 2. View of Filene Center from the SW side of our trail loop (see Fig. 1B), showing typical topographic relief at Wolf Trap park.

Figure 3. View of Wolf Trap creek where it enters the valley (Fig. 1B), showing boulders of Precambrian schist to be blocky–eroded nearby and gravitationally slid into creek but were not transported. These recently exhumed blocks are covered by Quaternary fluvial sediments, which are visible along the left side of the creek.

Figure 4. Large block (less than 6 feet in diameter) of schist that has been moderately weathered in place. Note the thin bedding (fissility) between thick layers with a conchoidal fracture pattern (center of image). This is the upstream side, which is pockmarked by rolling and bouncing boulders during high water. Mud becomes schist when buried deeply, retaining the lamination of the original fine-grained sediments, but remineralizing to familiar clays easily at the surface. Mud to schist to mud.

Figure 5. Meander in Wolf Trap creek along the north side of the park (see Fig. 1B), where a shallow pool of quiet water collects between runs (turbulent creek segments).

Figure 6. View looking upstream from a pedestrian bridge crossing Cthse Spring Branch, a tributary crossing our trail (dash line in Fig. 1B) before it joins Wolf Trap creek (NE side of trail in Fig. 1B). The boulders are smaller than downstream (Figs. 3 and 4), and their long axis are aligned with the stream flow. These angular blocks are sliding along on a stream-bed comprising miniature versions of themselves (note the clear view of the bottom in center of image). Even gravel and pebble-sized particles are platy because of the characteristic fissility of schist.

Figure 7. This photo dramatically reveals the effect of water on erosion.

Figure 8. This image is one I’ve seen too often here in northern VA. The sewer systems frequently follow streams because they are low points and run downhill (a good property for a sanitary system). However, when stream levels exceed expected values, the system is compromised and raw sewage can be released into the environment.

Summary. Over a billion years ago, this area was submerged beneath an ocean or marginal sea. Distant mountains eroded rapidly in a time before land plants. Vast quantities of sediment accumulated in layers of erosional debris that were subsequently buried by younger sediment. Between a billion and five-hundred million years ago, these sediments became rocks that were subsequently deformed as continental plates collided. They didn’t melt, however, and survived the cataclysm relatively unharmed, becoming schist and related metasedimentary rocks. For the last 200 million years, they have been slowly working their way to the surface as younger rocks are removed by water erosion in streams like we see all throughout NoVA. They are now exposed to the elements and are weathering to form new layers of sediment in the Atlantic Ocean, beginning a new cycle.

Slipping and Sliding: Holocene Landslides in Central Virginia

Introduction.

This post is a summary of a field trip I took during the Geological Society of America’s Southeastern Section meeting in Harrisonburg, Virginia: Ancient and Modern Landslides of the Eastern Blue Ridge of Virginia. I was joined by more than twenty geologists on this ten-hour excursion, which was led by two geologists from the Virginia Department of Energy. Thus, I’ll be adding my photographs and comments to the narrative supplied by our expert guides, as well as aircraft-flown LIDAR (Laser Imaging Detection and Ranging) data with one-meter resolution and maps compiled by the VADoE Geology and Mineral Resources division.

Debris flows have been identified in many places and certainly occurred throughout geological time, often associated with alluvial fans or volcanic eruptions. This post focuses on those which pose some hazard to the residents of Virginia and is not an exhaustive catalogue of all such features.

We looked at landslide deposits ranging in age from about 10000 years ago ( Holocene) to a debris flow created by a severe thunderstorm in 1995. Such deposits can be classified as modern, relict or ancient. As I understand these terms, modern can be attributed to a specific event. In geomorphology, a relict landform is a landform formed by either erosive or constructive surficial processes that are no longer active as they were in the past (Wikipedia). An ancient landform is from the geological past and has been extensively modified by surface processes, as well as burial and metamorphosis for very old rocks.

Any errors in my report are solely due to my misunderstanding what was presented on a topic I am unfamiliar with and not the leaders of the field trip.

Observations.

Figure 1. (A) The study area is located along the first ridge of the Valley and Ridge province of the Appalachian Mountains. Blue colors indicate higher elevations, including the Blue Ridge with peaks of about 400 m. The Blue Ridge is not strictly part of the Valley and Ridge; it is the result of a series of thrust faults which placed Precambrian metamorphic rocks over younger Paleozoic strata. (B) The field area (black ellipse) encloses a crenulated landscape comprising short canyons with steep slopes and rolling valleys. We visited the numbered stops in sequence.

Figure 2. (A) Our first stop was at Sugar Hollow Reservoir. An intense thunderstorm dropped torrential rain on the area in June, 1995, causing a debris flow that decreased the reservoir’s volume by 15%. (B) Looking uphill we see an undulating surface littered with angular boulders from the top of the hill (dashed line). (C) Streams have started eroding into the debris flow, revealing a jumble of boulders beneath the surface, as seen in plate D. Recent mass flows like this are recognized by an irregular surface and angular boulders that didn’t originate from nearby slopes.

Figure 3. (A) Stop two (see Fig. 1B for location) took us to a relict debris flow easily identified in this high-resolution LIDAR image (courtesy of VA Dept. of Energy). Note the hummocky surface which originates at the top of the ridge. (B) The slope is very steep here and there were no trails to the summit. The Moorman River is at the bottom of the slope. (C) Photo taken at the location of the triangle in (A). The image shows a cutout from the slope, indicated by dashed lines; the long dashes locate the top of the scarp and the short dashes the approximate location of the lip. Compare this to the LIDAR image in (A), which shows a depression with a slight lip. There was a dramatic change in surface morphology along the slide, which is delineated by downslope ridges on either side.

Figure 4. (A) Map of a debris flow (aka alluvial fan) at Mint Springs Valley Park, stop three in Fig. 1B (map courtesy of VA Dept. of Energy), showing how it was focused on the small lake at the park. Further up the valley, large boulders became apparent, but the landscape had been massively altered during construction of homes. (B) At the park, the slide appears as a smooth (graded) surface devoid of large boulders.

Figure 5. Ancient landslide deposit at Stoney Creek Park (stop 4 in Fig. 1B). (A) A stream-cut cliff revealed weathered Precambrian granulite directly overlain by a unit composed of angular-to-weathered boulders supported by a fine-grained matrix. The original bedding of the granulite, which originated as a sedimentary rock (probably sandstone or arkose) is labeled. The original sediments were deeply buried to reach such a high metamorphic grade, before being uplifted and eroded to create a surface on which the debris flow was deposited, probably in the precursor to the modern stream. (B) Detail showing the characteristic matrix-supported structure of the debris flow. This flow is interpreted as older, due in part to the extensive weathering of the clasts it contains. There was a lot of mud moving with these boulders.

Figure 6. Ancient landslide deposit at Stoney Creek Park. (A) A debris flow is exposed as a planar surface on top of alluvium. Other flows are suggested by the exposure of boulders lower within the section, but it was difficult to be sure because of collapse of the upper surface. (B) This detailed image of the surface deposit reveals a higher concentration of boulders than in Fig. 5. They are also more rounded. This suggests fluvial reworking, which would have removed much of the fine matrix seen in Fig. 5. This flow, and others lower in the section, are considered to be younger in age, although radiometric dating is not available. Furthermore, the geologic map from Rock D (not shown) indicates several faults aligned with Stoney Creek, suggesting that uplift contributed to mass wasting of highlands to the west.

Figure 7. Stop five, Edgewood Farm (see Fig. 1B for location). (A) Geologic map from Rock D, annotated to show the source of material for a slide that was concentrated on a farm (blue circle) by a narrow gorge. (B) view looking WSW towards Mars Knob, showing the toe of the debris flow that resulted from heavy rain during Hurricane Camille in 1969. (C) Large boulder at the entrance to the canyon, marking the extent of transport of such debris. (D) Hummocky and boulder-littered surface within the arroyo, similar in appearance to stop one (Fig. 2).

Figure 8. Images further upstream at stop five. (A) The north side of the valley is blocked by debris, including large boulders (>4 feet). (B) The south side seems to be less congested, and the stream has eroded a new channel through less-resistant material although the bed comprised smaller boulders (<2 feet). Such a large volume of material originated from a large source area (Fig. 7A) that was saturated by heavy rain, transporting a massive amount of rock debris with a relatively small amount of mud.

Summary.

I have only briefly summarized all the information supplied during the field trip. Nevertheless, these observations reinforce my previous opinion that surface erosion is dominated by episodic events. From thin layers of sand on alluvial fans, flood deposits along large rivers like the Mississippi, and storm beds on the continental shelf, to pyroclastic flows and fluvial/alluvial debris flows like these, Mother Nature doesn’t do anything slow and easy. It’s more like wait and wait … then all hell breaks loose.

At least that’s what I think …

Acknowledgment.

Figure 9. This field trip was led by Wendy Kelly (left) and Anne Witt (right) of the Virginia Department of Energy’s Division of Geology and Mineral Resources. Their expertise made this a very enlightening and geologically uplifting experience. I will certainly be on the lookout for evidence of debris flows as I continue my geological adventure.

Washington Monument State Park, MD: Familiar Cambrian Metasediments

Figure 1. Looking west from Washington Monument, atop the Blue Ridge in Maryland. The valley is equivalent to the Shenandoah Valley in VA (see Fig. 2), but I couldn’t find a map with it labeled. The Appalachian trail follows the ridge through MD; we encountered it a few miles south of here in a previous post. We expect to see some of the same Proterozoic-to-Cambrian (2500-500 Ma) metasedimentary rocks here that we saw before, in addition to a surprise from an older post.

Figure 2. The field site. Washington Monument is indicated by the purple circle and arrow in the large map. The first inset map shows the geology around the monument. Note the mismatch in geology from different quadrangles; this must be a problem with either the data or Rock D, but the units (indicated in the smaller inset map to the right) were consistent when I clicked on a point. My home is indicated by the star, so you can see we haven’t traveled far. ATWC refers to the Appalachian trail at Weverton Cliff, MD, which I recommend you read to get some background. BRNP represents Bull Run Nature Preserve, which I posted last year. The geological legend for the detailed inset map is at the bottom of the figure. Note that Ma stands for a radiometric age of one-million years; this age is indicative of cooling below the threshold to set the atomic clocks within the minerals, but sedimentary rocks can’t be dated this way. Therefore, these are dates when deep burial and/tectonic deformation/magmatism ceased (i.e. when an orogenic period ended).

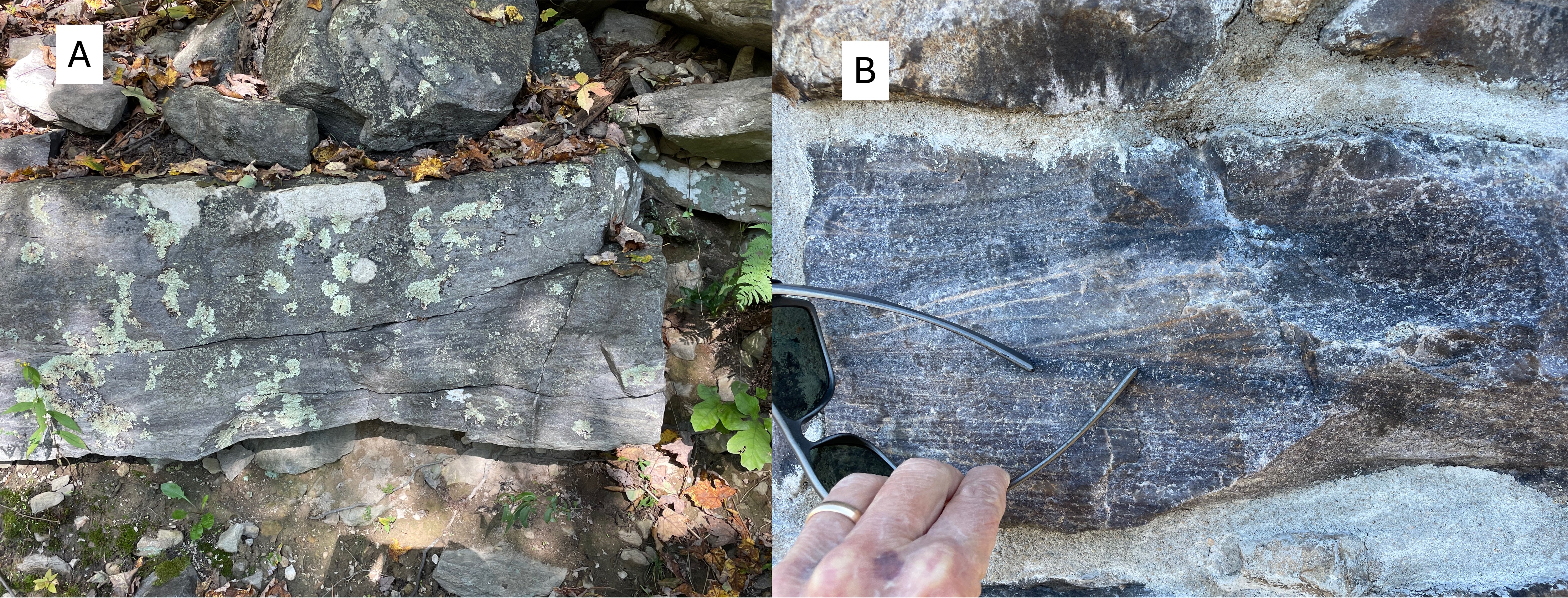

Figure 3. Rubble near the monument that resulted from in-place weathering of Weverton Formation rocks (Cw1 and Cw2 in Fig. 2). All of the weathering products (e.g. clays and carbonates) have been washed away, leaving large slabs (~6 feet) piled up. This is a common feature of rocky knolls with good drainage.

Figure 4. (A) Outcrop of older Weverton formation rocks (Cw1 in Fig. 1), revealing weathered material below and boulders on top. This outcrop contains cross-bedded layers on close examination. (B) Photo of a block of Cw1 used in the monument , which shows the crossbedding better than panel A because a fresh surface was cleaved during a recent repair of the 30-foot tower. The color is important: green sedimentary rocks like these represent marine environments, where there is less oxygen; sedimentary rocks deposited in rivers tend to be reddish because of oxidation (rusting) of Fe-containing minerals. These are probably shallow marine sands.

Figure 5. (A) Quartz in a vein (<1 inch thick) from near the monument. Note that the cross-bedding is very similar to Fig. 4 but more weathered. (B) Less-common view of a quartz vein seen obliquely, showing the surface that was against the country rock. These veins would have been injected during a period of magmatism, sometime between 2500 and 511 Ma; I can’t be more specific because I don’t know exactly where the radiometric ages were measured within these rocks. However, the Weverton formation is approximately 4500 feet (1.4 km) thick here; thus it’s possible that these rocks were deposited episodically during this immense time interval; but no unconformity (i.e. erosion or non deposition) is mentioned in RockD.

Figure 6. View looking east from the Appalachian Trail, showing the terrain typical of the Appalachian foothills. To the left of center, outcrops of Weverton rocks (Cw1 and Cw2 in Fig. 2) can be seen.

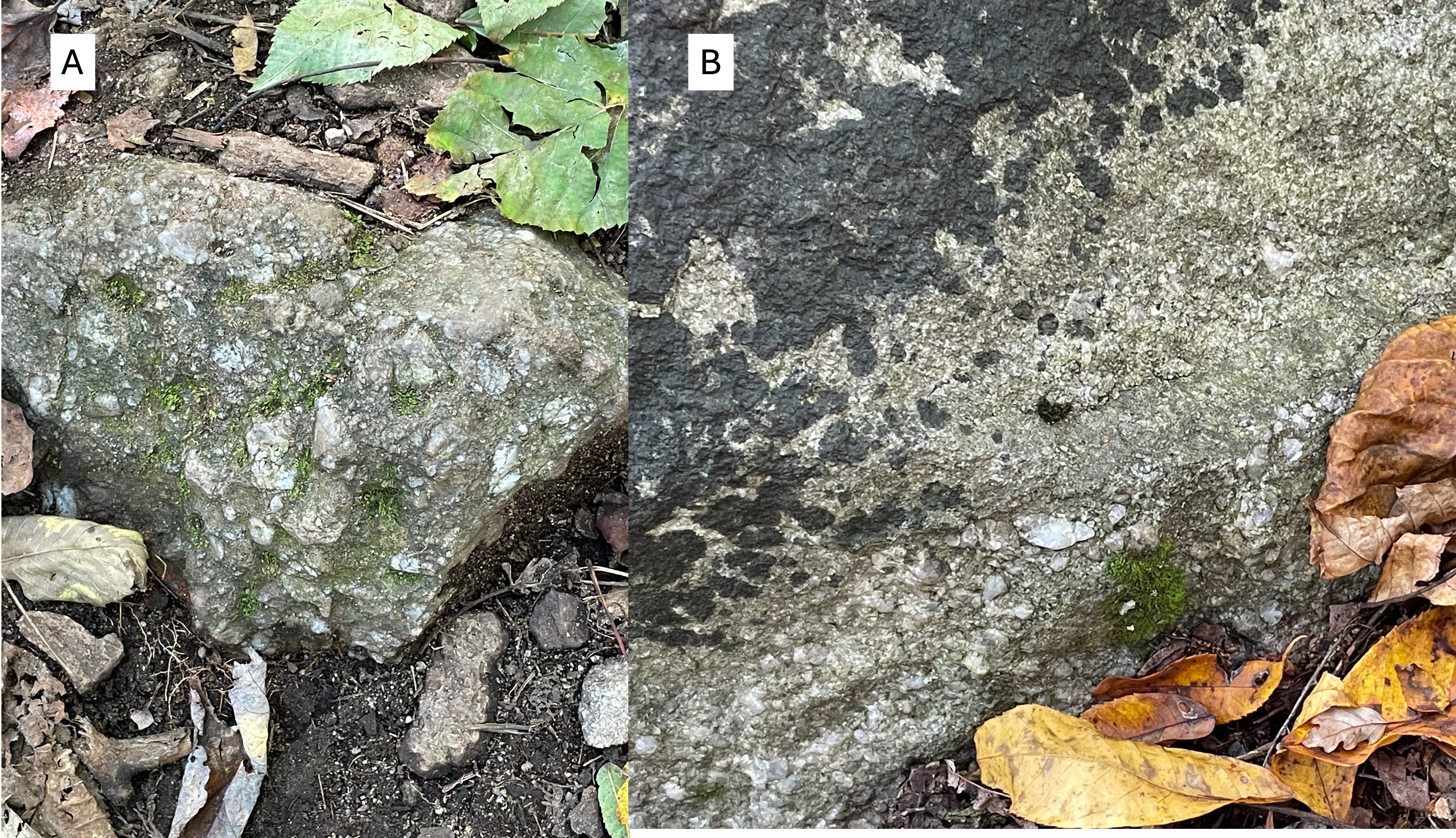

Figure 7. (A) Boulder (~2 feet across) of arkose, revealing angular clasts of rock fragments in a sandy matrix. (B) Poor outcrop of conglomerate with rounded rock and quartz in a similar, sandy matrix. Comparing these images to Fig. 4 shows the variability of sedimentation (and thus depositional environment) during relatively short time intervals (say … tens of millions of years, for example). This kind of variability implies changing sediment sources, possibly caused by tectonic uplift (with magmatism) to the east.

Figure 8. This figure is from the Bull Run Nature Preserve field trip. It is a schematic of how layers of sedimentary rocks (shown in different colors) can slide over one another along thrust faults. This process results in stacking of similar sediments, making stratigraphic analysis of sparse field data problematic. The rocks on the left are sliding upward to the right along a series of thrust faults (dashed line). At Bull Run Nature Preserve, a fault like this could be identified by older rocks clearly being stratigraphically higher than younger ones. That isn’t the case at Washington monument, where the interleaved rocks (blue and green) are too similar in lithology and age to be differentiated.

SUMMARY

The thrust fault labeled in Fig. 2 has been confidently identified (represented by a solid line), no doubt through more investigation than I was willing to spend time on. This unnamed fault underlies the northern Blue Ridge, and marks the beginning of the Valley and Ridge province; the Blue Ridge was thus an anomaly, which has been identified as a belt of older rocks thrust over younger ones about 500 million-years ago, when the supercontinent of Pangea was being created.

We have followed the Weverton formation through time (2500-485 Ma) and space (more than 40 miles). During this unimaginable interval, this small piece of the Earth’s crust has moved thousands of miles. Only the last 500 my of its journey is known with any confidence. This tectonic plate has been carrying these sediments to unknowable latitudes, colliding with immovable objects while spreading the remnants of mountain ranges that are now forgotten, deconstructed by the irresistible power of water, wind, ice and time.

Some things aren’t meant for us to know …

Recent Comments