Shenandoah National Forest: Precambrian Volcanism

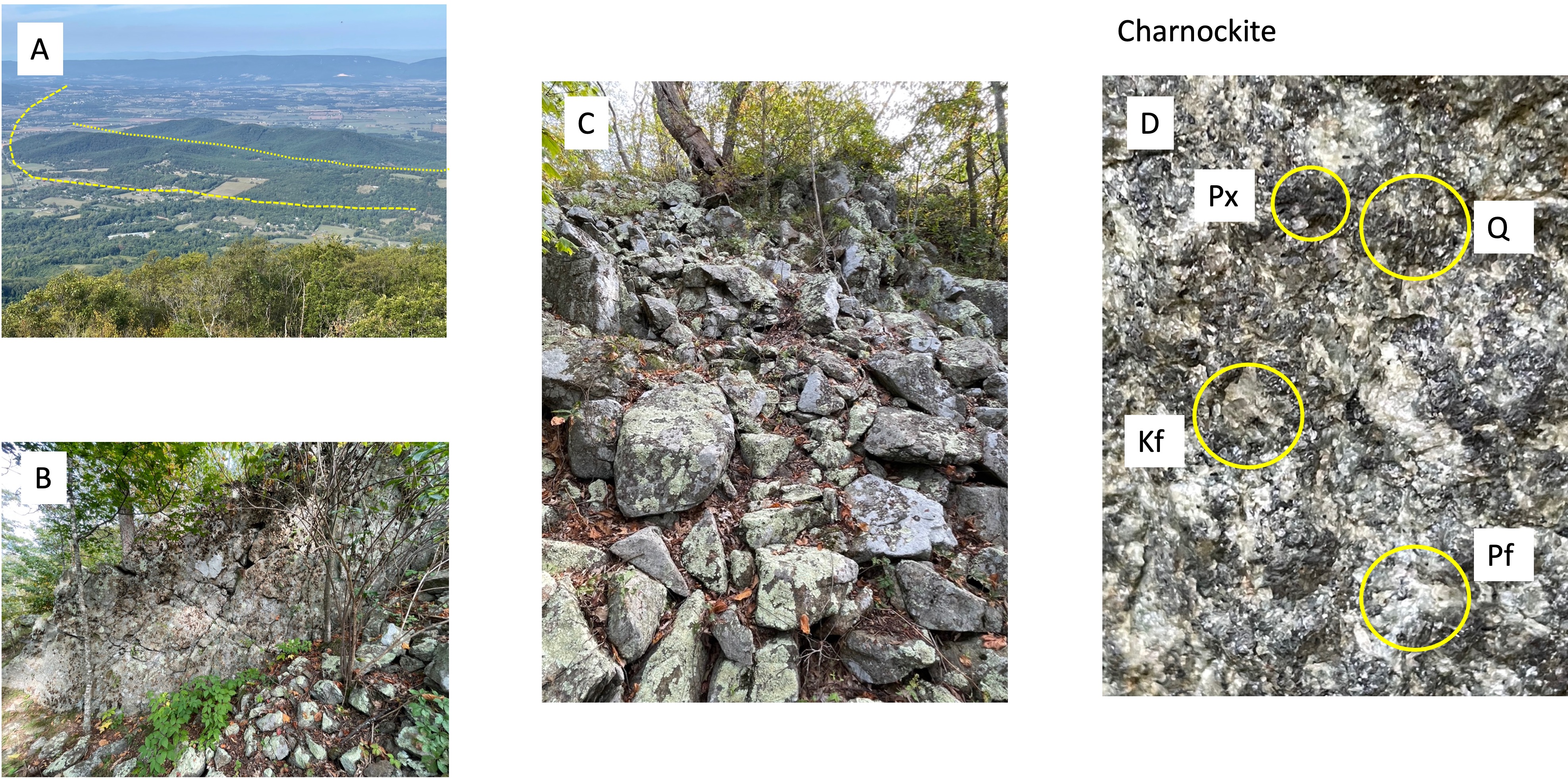

Figure 1. View looking SW at Shenandoah Valley from Miller’s Head (3484 feet elevation). The forested hills to the center-left are Precambrian metamorphic rocks (1600 – 1000 Ma), separated by an arcuate fault from Paleozoic sedimentary rocks (540 – 250 Ma) that get younger to the west. The ridge in the distance is constructed of Devonian rocks (416 – 360 Ma) whereas the closer ridge is Ordovician to Silurian sandstone (443 – 419 Ma). Today’s post will examine the Precambrian rocks that comprise the Blue Ridge Mountains, which we saw in a the last post and in a previous post.

Figure 2. (A) Map of northern Virginia (NOVA) showing my home (star), Washington DC, and the study area in Shenandoah National Park (rectangle in lower left). The inset photos show the stunning views to be found in the lower part of the study area. (B) Geologic map of the study area, showing Precambrian rocks in pink shades and Cambrian rocks in brown, Ordovician in green, and Devonian strata in orange shades. The Shenandoah Valley forms a syncline with smaller folds contained within it, like folds in a rug. Younger rocks are exposed by erosion along the axis of a syncline. The solid lines are faults that have been identified in the field although the kind of fault can’t always be determined.

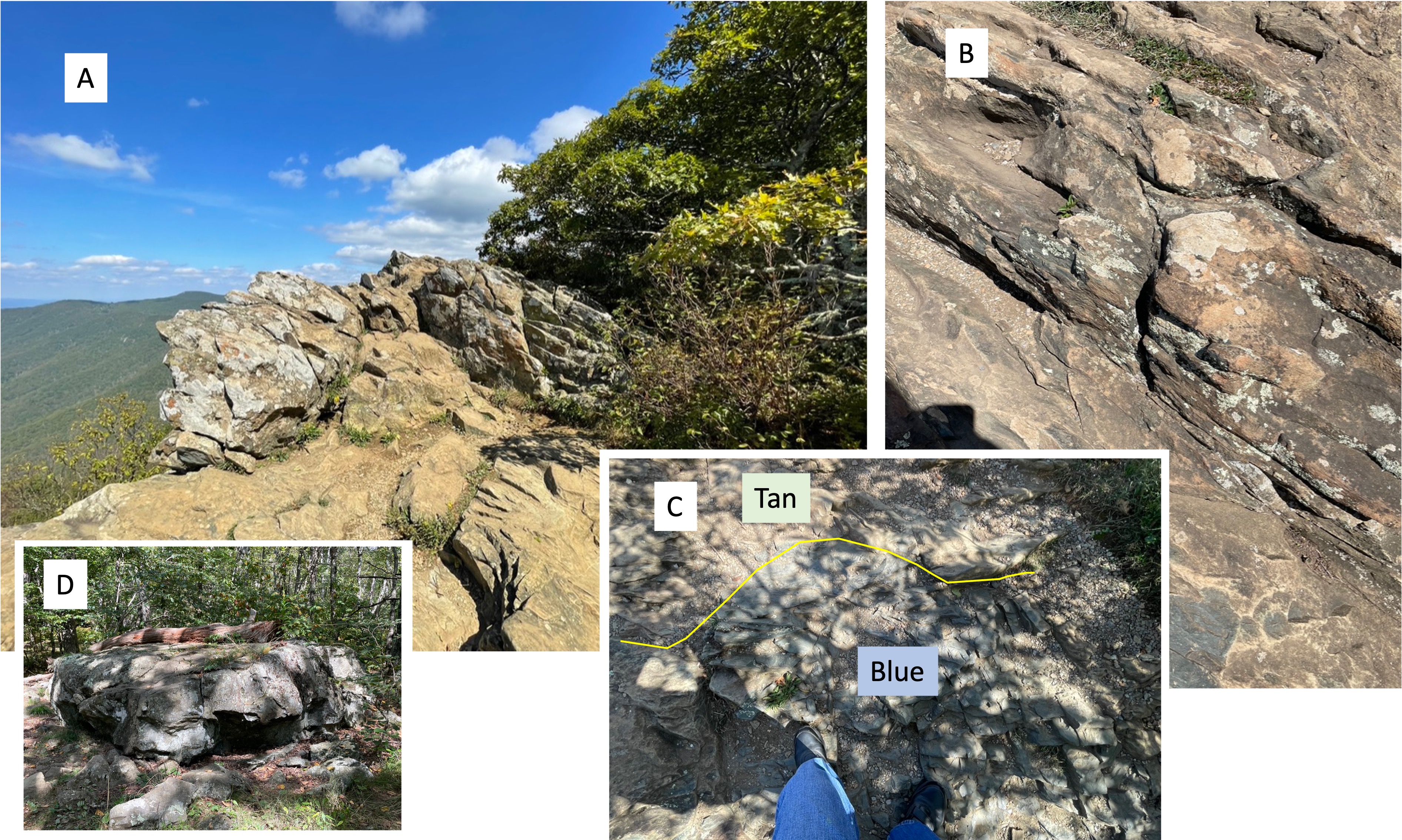

Figure 3. Images from Hawksbill Mountain (elevation 4042 feet), the highest point in Shenandoah National Park. (A) View looking north, showing bedding planes dipping to the SE as we’ve seen throughout NOVA. This is the general structural trend along the eastern margin of North America. These volcaniclastic deposits are part of the Catoctin Formation, dated by radioisotopes to between 1000 and 485 Ma. (B) A close-up shows that these rocks are fissile, which means they are forming thin layers as they weather. They were originally very fine grained, possibly ash or mud (clay minerals) and other weathering products. (C) This photo reveals (despite the dappled shade of trees) a contact (yellow line) between tan and bluish rock that has no other distinguishing features. This must be caused by a slight difference in composition and/or texture that leads to subtle variations in reflected light; if I may speculate, I think the blue ash/sediment filled a depression in the tan material; however, this conjecture is based on the physical environment when this volcanic material was produced. Eruptions were not continuous and there was always a slightly weathered surface upon which new ash was deposited. (D) Outcrop of Catoctin Formation rocks about 600 feet lower than the summit, and much further down-section from the rocks seen in plate A. This basalt/ash was deposited millions of years before what we see in plate A and the magma chamber would have evolved substantially. The original bedding is, as near as I could tell, nearly horizontal rather than tilted to the SE. This implies that brittle deformation (i.e. faulting), which occurred tens of millions of years after eruption, subsequent burial, and metamorphosis, was localized within the larger body of Catoctin Formation rocks (3000 feet thick and extending for many miles); in other words, these metabasalts were hard as rocks (as they say) when they were compressed horizontally. Perhaps they were even transported tens of miles along a thrust fault? We saw evidence of a Precambrian thrust fault at Bull Run Nature Preserve.

Figure 4. Catoctin Formation metabasalts at Dark Hollow Falls. (A) These rocks don’t form sheer cliffs, so this creek flows over a series of ledges for a vertical distance of about 70 feet.(B) The bedding is tilting to the SE as at Hawksbill summit and contains fissile layers as seen here, intercalated with massive units as seen in plate A. Also note the dark layer in the center of the photo, which may be similar in origin to the blue layer seen in Fig. 3C. (C) Representative boulder of the rocks at Hollow Falls. Notice the white flecks in this sample, which is about 18 inches in length. (D) Close-up of the larger light-colored ellipse in the lower-left part of plate C, showing concentric rings of light material (probably quartz) in a fine matrix (probably basalt). This is an amygdule, which is a mineral filling a cavity in a volcanic rock that is filled with vesicles. The vesicles are originally pockets of volcanic gasses that are trapped when the basalt is erupted, and then fill with hydrothermal fluids which deposit minerals. (E) Bedding surface showing many semicircular ridges, which are (probably) remnant from when this basalt was exposed to the atmosphere and the gases escaped; in other words, this was the top of a basalt flow whereas plate D was too deep within the flow for the gas to escape before the basalt solidified. A moment in time frozen for more than 500 million years.

Figure 5. Photos of Miller’s Head. (A) View looking west (see Fig. 2B for the geologic map). The yellow lines approximately outline faults within the Paleozoic rocks underlying Shenandoah Valley; note that one curves to the west where Neoproterozoic (1000 – 542 Ma) rocks jut into the valley. The second fault borders a low ridge comprised of the same rocks we found on this peak. (B) Vertical joint that shows intersecting joints (the X’s seen in the rock face). Water seeps in through this system of fractures and weathers the rock into blocks. (C) The result of this weathering process is a mountain covered by a veneer of rubble. The entire mountain in this area is turning into a pile of boulders that look like they were pushed aside by a bulldozer, but they haven’t moved other than sliding over one another down the steep slope. (D) Close-up (4X magnification) of a fresh surface of this rock, which is Charnockite, a granitoid rock that contains pyroxene minerals, which do not occur in granite. This sample reveals quartz (Q), plagioclase feldspar (Pf), potassium feldspar (Kf), and a lot of pyroxene (Px). Note that Pf is white and not dark, which would be more indicative of a mantle source, and pink Kf which is typical for a granite formed from crustal material. Charnockites are enigmatic and almost entirely found in Precambrian rocks. According to RockD (radiometric dating), these intrusive rocks are between 1600 and 1000 million-years old.

Summary. This post doesn’t add anything new to what we’ve already learned from previous field trips but it reinforces the picture that has been developing from our previous posts in NOVA and elsewhere; tectonic plates were colliding along the eastern margin of North America as long ago as 1.6 billion years, while muddy sediments were being deposited in deep water (below wave base or rivers), and continued doing so until about 500 million-years ago. This was a discontinuous process and, considering the billion years duration of this tectonic upheaval, it is possible that multiple mantle plumes were competing for space. Such a huge span of time could easily encompass more than one Wilson Cycle, but the best I can say in this post is that the Proterozoic (2500 – 542 Ma) looks to have been as active an age as we’ve seen in the last 500 million years.

One final note. The earth is cooling very slowly but, nevertheless, it was hotter in the Precambrian. This means that plate tectonics, driven by mantle upwelling (i.e. plumes) would have been more vigorous although not by an order of magnitude. Thus, given the immense span of time between the Middle Proterozoic (1600 – 1000 Ma) Charnockite we encountered (Fig. 5) on this trip and the Catoctin Metabasalts (1000 – 485 Ma), it is safe to say that we haven’t seen the whole story.

The rocks speak softly but they know the truth …

Recent Comments