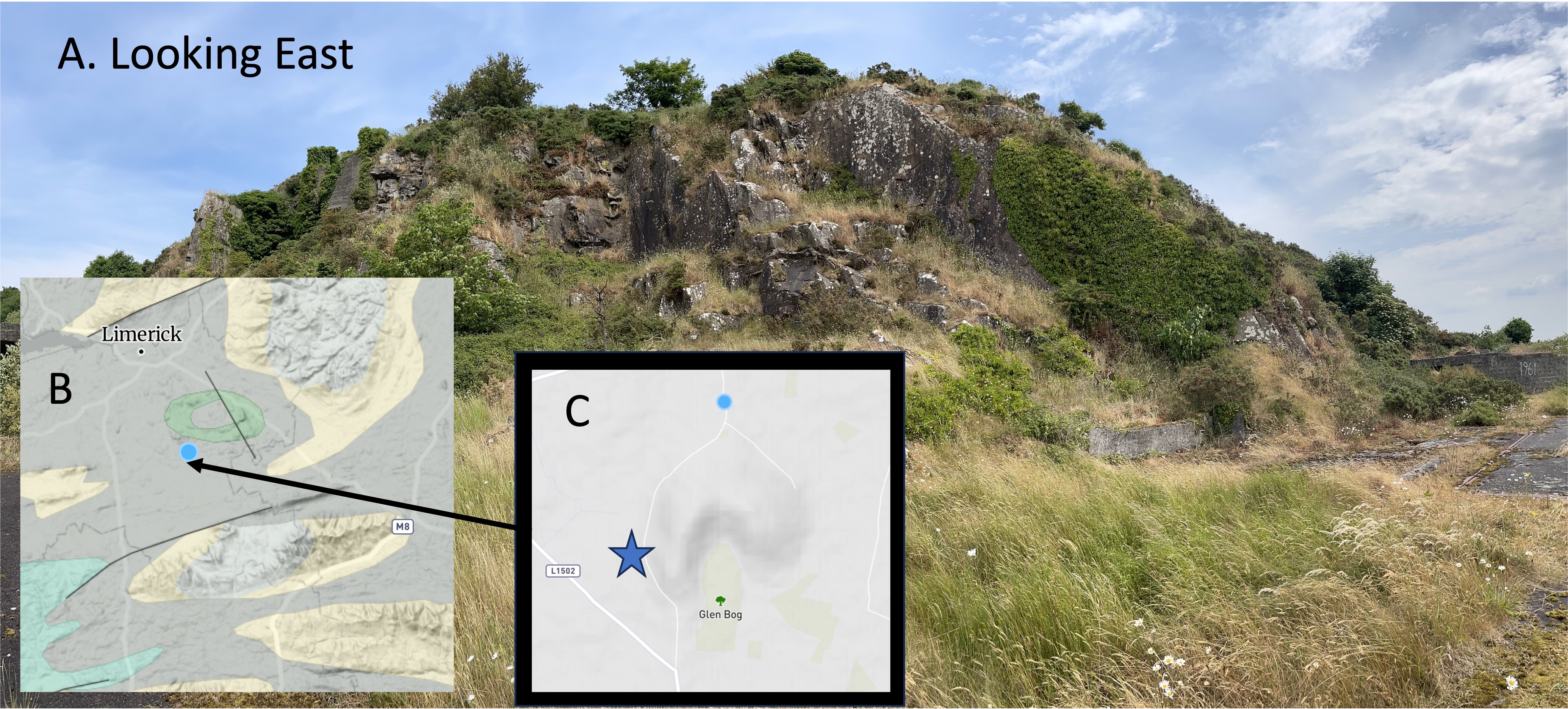

Deformed Marl at Knockainey

Figure 1. (A) This hill is more than 50 feet high, standing out above a gently rolling countryside. It got my attention because it looks like another source of building stone in a farming area the walls between fields are built of field stone. (B) The location places it just south of metabasalt alluded to in a previous post, which is the ring of light-brown on the inset map from Rockd. The major lithology of the green area is limestone, with some clay and sandstone; this Early Carboniferous (360-323 Ma) limestone is coeval with the rocks from Loch Gur. (C) The distinctive shape of the hill is seen in the topographic map The star is the small study area, located near the remains of an abandoned automotive service facility.

Figure 2. The rocks here are relatively massive but larger, in-place, exposures had a common plane oriented approximately like those labeled “Bedding Plane” in the photo. These beds are close to vertical whereas those at Loch Gur were much less steep. This could have been caused when the basalts (brown ring in Fig. 1B) were emplaced sometime after burial; the forced eruption of basalt would have folded the layers of limestone back like a flower opening.

Figure 3. Close-ups of boulders lying at the base of the cliff (inset photos), reveal similar textures but have slightly different hues; plate (B) is slightly redder, but both have a texture similar to unweathered limestone we saw near Loch Gur. The surface color is caused by the weathering of iron-bearing silicate minerals like amphibole and biotite.

Besides the color, there is another important difference between these samples and those: there is no evidence of the dark inclusions we saw at Loch Gur, which were also absent in the rocks from the stone circles described previously. There are also no dissolution cavities in these rocks, as seen at the quarry.

The photos in Fig. 3 have black circles drawn around inclusions. They are representative only. Some of these inclusions appear to be regular (e.g. the lowest circle in Fig. 3A) whereas others are highly irregular, such as the leftmost circle in Fig. 3B. These are NOT fragments of rock, or sand grains; however, they may be the remnants of fossils within the original carbonate sediments that were partly dissolved during burial.

Figure 4. This boulder has a surface layer (labeled “Spalling layer”) that has separated from the subjacent, unweathered rock. This delamination occurs because the weathering products (e.g. limonite and hematite) of minerals high in iron (e.g. amphibole, biotite) expand in volume; consequently, this boulder is peeling like an onion, exposing an unweathered, gray layer.

Mixtures of carbonates and clastic sediments are called marl or marlstone. Typically, marlstone incorporates so much sand and silt that it doesn’t become very hard and is thus crumbly. However, without using a petrographic microscope to observe the composition of the rock, I can’t say if it’s 5 percent, 10 percent, or 20 percent terrigenous sediments — so it’s marlstone.

This post isn’t a summary of the geological history of Ireland, so all I will say in summary is that these rocks verify what I suspected already: a broad, shallow sea (e.g. a bay or estuary) began to receive sediments eroded from mountains between 360 and 320 Ma; the percentage of siliciclastic sediments increased to the point that, sometime after 320 Ma, this area had become part of river delta, as we saw at Foynes in the last post.

Trackbacks / Pingbacks