What Came After: Carboniferous Shales at Foynes

Figure 1. View looking west along the southern shore of Shannon Estuary in the town of Foynes. The ridge in the image got my attention, so I investigated it further. The gently rising land to the right is Foynes Island, which is elevated but not as high as the ridge.

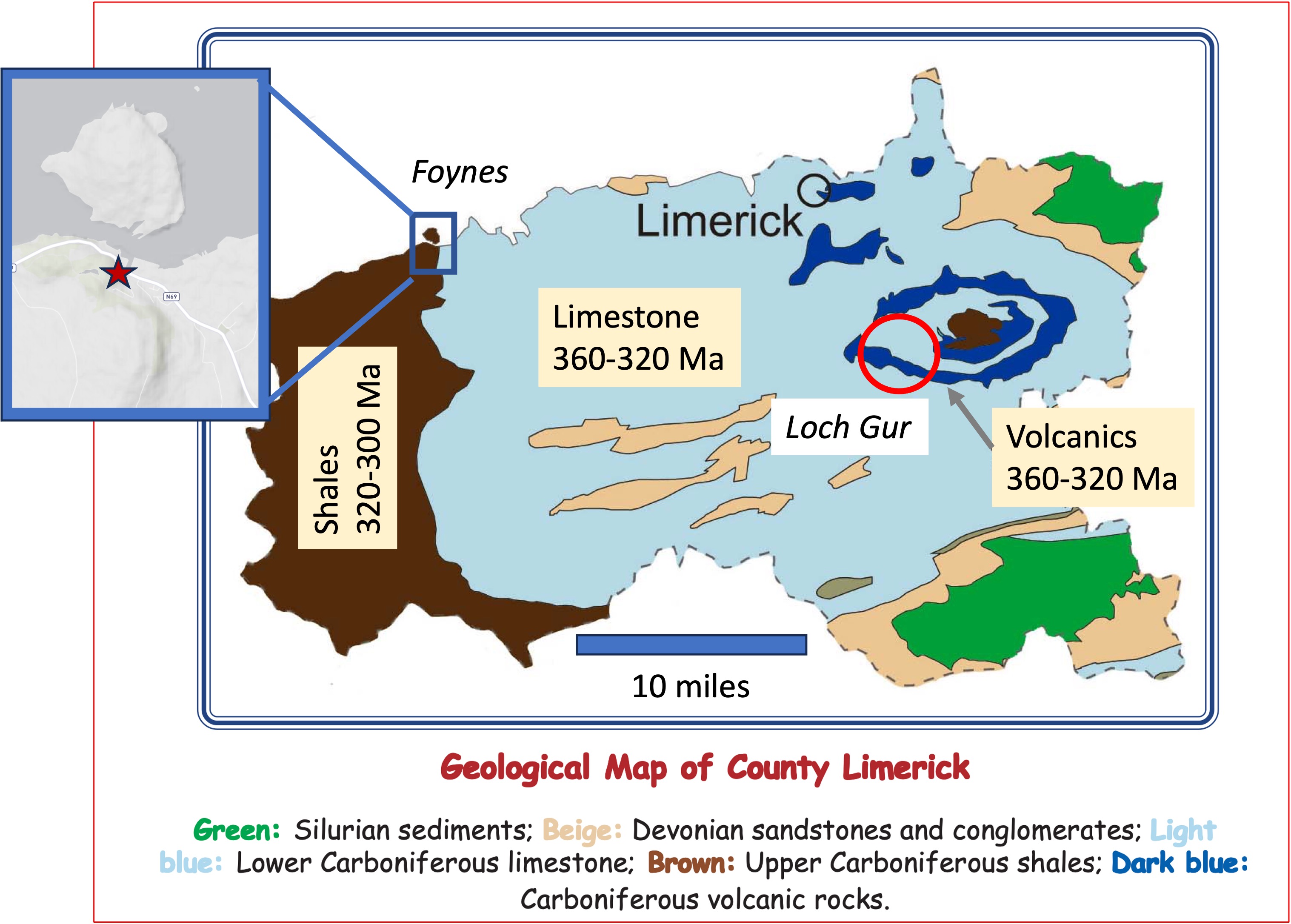

Figure 2. My last post was from Loch Gur (red circle to the right), where we saw limestones with evidence of contamination by terrigenous sediment (i.e. mud) and no fossils. These chemical/biological sediments were deposited between 360 and 320 Ma (Ma refers to mega annums, roughly millions of years ago). This post travels thirty miles westward to Foynes (blue rectangle), where we discovered the ridge in Fig. 1. These are slightly younger shales geologically. The inset map shows the topography of Foynes (the star is the location of Fig. 1); the ridge follows the outline of these rocks on the geological map (brown).

Figure 3. The left image shows the bluff (see Fig. 1), which is composed of mud, sand, and silt. The white circle is shown in more detail in the center photo: Massive sand/silt beds sandwich a thick sequence of thin layers of fine-grained sediment with a dark color, which suggests a high organic carbon content (i.e. decayed plant matter), low-oxygen environment. For example, black shale may form in stratified, shallow seas and is a source of petroleum.

The orange circle was photographed at higher resolution in the right image, which shows thin layers of sand/silt intercalated with fine-grained, dark laminae. Sand balls and lenses (labeled in the figure) suggest that sand was deposited into unconsolidated mud.

One depositional model that is often applied to these kinds of sediments is the Turbidite; coarser sediment slides down steep delta fronts, often activated by wave action, and form discontinuous layers inches in thickness, in deep water. Another, simpler, model is deposition in tidal flats where daily flows slowly sort the fine and coarser sediment into interweaving layers. Without more data, it isn’t possible to choose which is more likely; however, both would occur in similar environments: deltas where rivers debouch into a sea. The brief explanation of these rocks in RockD suggests they are turbidites, although it is likely that the depositional setting changed over time, as we’ll see in the next figure.

Figure 4. This section was exposed about 200 feet from Fig. 3; the rocks here are dipping about 30 degrees away from the camera, so I estimate that this exposure is about 100 feet (this is a “back of the envelope” estimate — a guesstimate) further up-section. These layers are younger than those seen in Fig. 3; using a sedimentation rate of 5 mm/year (I do calculations in metric units), these mixed sediments were deposited less than 10,000 years later.

During that interval, the supply of silt/sand increased substantially; here we see mud at the bottom, then thick (~1 foot) beds of silt/sand appear, first as discrete beds separated by muddy sediment, then as massive layers with no discernible cross-bedding. The white, dotted line is an approximate depositional surface that shows how the silt/sand might have filled low points in the seafloor, or formed sand bars. Turbidite layers as thick as the silt/sand bed at the top of the exposure are uncommon because that is a lot of sand to be mobilized in one event and it is very uniform in thickness.

The photos at the right represent the change in depositional environment that might have occurred during the approximately thousand years required to deposit these sediments. The lower image shows a series of turbidite layers at the bottom of a marine delta; the upper photo shows a typical depositional environment for massive silt/sand beds, with muddy sediment limited to mud flats.

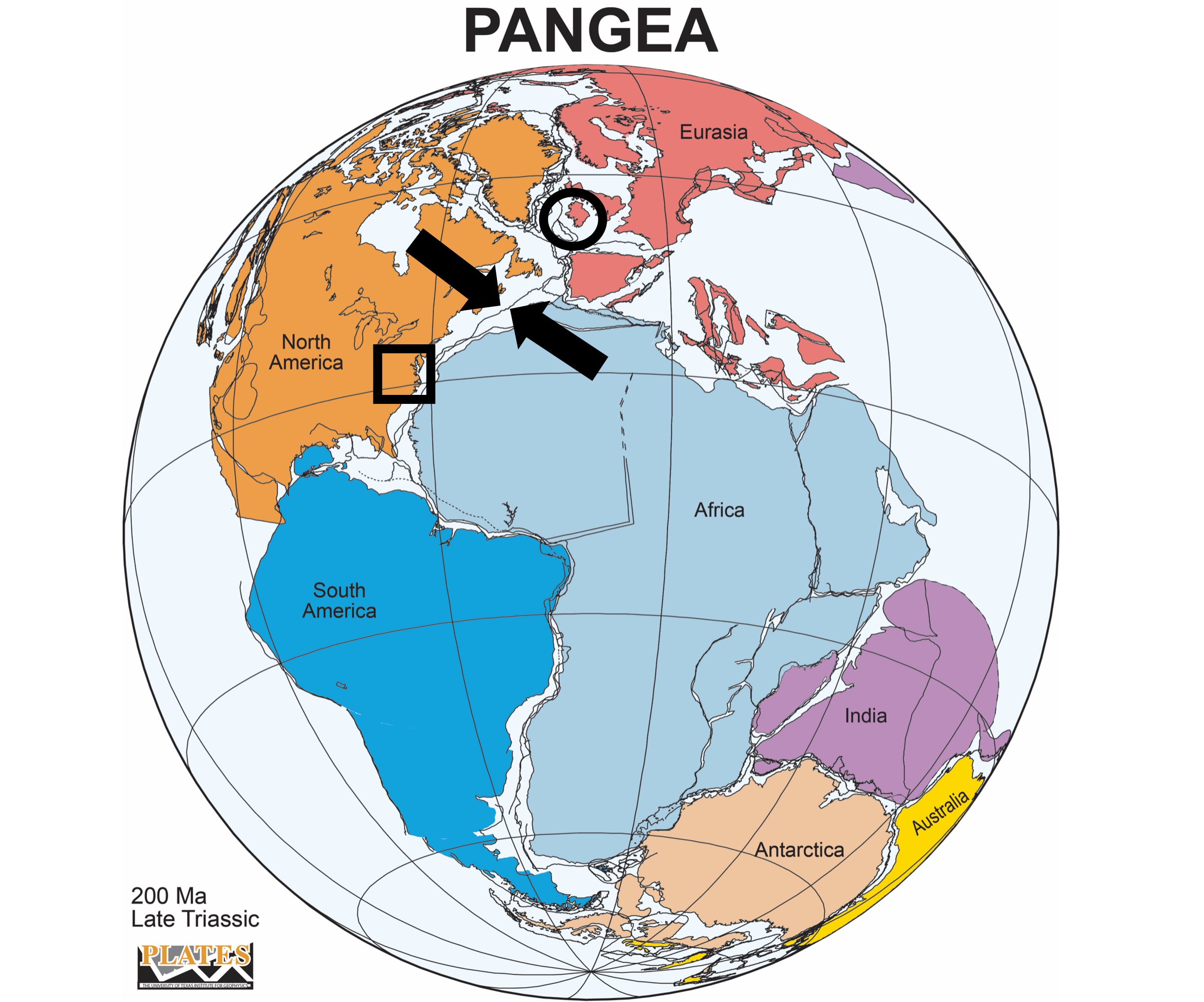

Figure 5. Reconstruction of Pangea 100 Ma after the rocks we saw at Foynes were deposited (circled area).

The section exposed at Foynes represents about 10,000 years of nearshore deposition between 320 and 300 Ma. When we put this together with the rocks we saw at Loch Gur, we see a classic coarsening-upward sequence.

These can be short or long and be caused by many processes: for example, a single sediment source can be rising and dumping larger grains, which cannot travel as far as mud; however, this is a much slower process than the 10,000 years represented in this exposure. It is also possible for several sources (e.g. different mountains in the area) to contribute sediment at different times as they erode. Sea level can fluctuate, changing the potential energy of transporting streams, but this is also a slow process; for example, sea level fluctuations within a ten-thousand year interval wouldn’t be more than a few meters. It is also possible that, as mountains erode, different rocks are exposed and contribute to the sediment load.

I favor the turbidite model with this caveat: Sandy event beds, especially thin ones as we see here, can be deposited in relatively shallow water where sediment input is high and produce gravity flows generated by waves or earthquakes. This model would allow the relatively rapid change in environment, to one more like the delta seen on the upper right of Fig. 4.

One fact is indisputable, however, over millions of years this location evolved from quiet water, where calcium carbonate (primarily from the shells of marine plants and animals) collected, to a deltaic environment with large volumes of terrigenous input.

In other words, what happened in Northern Virginia (square in Fig. 5) about 500 Ma reached Ireland 200 million years later.

The sediment didn’t come from the same mountains — not that far away — but something new …

Trackbacks / Pingbacks