Publications: Deep Dives into Science Fiction

I’m not reposting these book descriptions in chronological order. They were originally written as my interest changed through time and in response to the news. This post focuses on four science fiction novels inspired by the news, and my visceral reaction to the simplified reality portrayed in pop culture. Thus, my attention turned to early reports of Artificial Intelligence, as Large Language Models were presented to the public. All the hype about deep-learning algorithms becoming intelligent after being trained on vast amounts of publicly available books, movies, images, etc. bothered me because, if the objective (intentional or not) is Artificial General Intelligence, these programs all missed the boat. For example, a human brain isn’t fed a stream of data to become the cognitive wonder we claim to be; it spends years processing and assimilating sensory data–touch, hearing, smell, sight, taste. So I imagined what might be occurring in a private lab somewhere, an event so profound it would change the course of civilization. It remains entirely possible that a scenario like that portrayed in Aida is actually playing out below the radar of mainstream media attention.

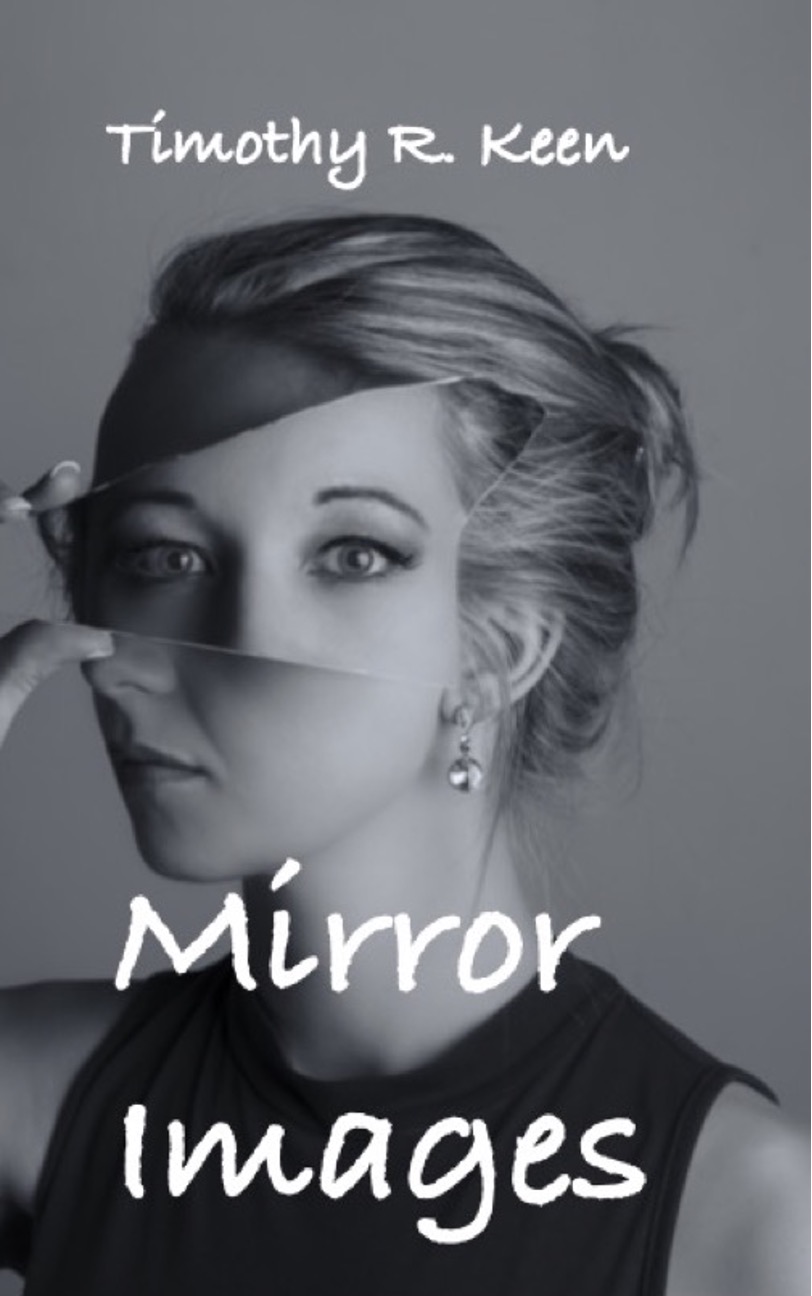

AIDA is an acronym for Artificial Intelligence Daughter Algorithm. It is the story of a heartbroken computer scientist who decides to create a daughter to replace the one he lost, along with his wife, during childbirth. But his creation exceeds his wildest expectations. The simple cover encapsulates the central theme of the book. Look at the picture closely and you will find that the beautiful woman depicted in the left side of the face is matched by an evil countenance on the right. There is no purpose in issuing warnings about unintended consequences because humans never look beyond the immediate horizon.

Writing Aida got me to thinking about AI and robotics so, naturally, I wrote another book on the subject. I wondered what would happen if an AGI hooked up with an advanced humanoid robot. One possibility is encapsulated in the title of this novel: it would be a Black Dawn for humanity if the wrong people got their hands on it. I wanted to call this book, AMANDA, the name of the central character. As you might have guessed that is an acronym–AMANDA is an Autonomous Mobile Anthropomorphic Neural-synthetic Deep-learning Architecture that has spent 16 years being raised as the daughter of a couple of computer scientists.

The naive Amanda needs a guide for her intellectual and emotional journey when her family is murdered and her body stolen. To add an interesting twist to the tale, I reintroduced the elderly writer from A Change of Pace as the author of the novel that influenced her parents: Aida not only impacted AMANDA’s creators, it also leads to its author (Jim Walsh) being pursued by the bad guys. Naturally, Amanda and Jim become unlikely partners in a quest of personal importance to both of them.

This is an adventure that doesn’t slow down until the end.

Apparently, I needed more adventure after writing Black Dawn, so I wrote a what-if novel about what might happen if the basic laws of physics, or the constants we take for granted, were to change. The result is Broken Symmetry, a story about a graduate student who finds herself the locus of a bizarre chain of correlated events–personal, social, and even geological–with no obvious causation.

The action in this story is too cataclysmic to keep under wraps, not when the San Andreas fault ruptures and Yellowstone caldera explodes, but that’s only the geological story. People begin to change and someone wants to stop the contagion. (Don’t they always?)

The Edge of Space was my response to a news story about Voyager One having communications problems after exiting the solar system. The story is told through the eyes of several characters with different perspectives. Their interactions are rife with speculation about what is occurring, from a young woman from Thailand to the president of the United States. As the story unfolds, these characters move in and out of each other’s lives.

I have written an outline for a sequel to this story of First Contact…

Publications: A Change of Pace

As much as I enjoyed writing the Unveiled books, I was ready for a change and, besides, I had some more issues to work through. I’m not generally a conspiracy fan but 9/11 got everyone’s attention, especially with that whitewash report the federal government produced. However, in Night Shift, I got distracted from the conspiracy theory and really dug into a tragic relationship between two people who couldn’t have been more different.

This book was a lot of fun to write, even though part of the story was tragic. I felt as if I knew Faheem and Sofia personally by the end. What a crazy couple, but they stuck it out despite their differences and what was happening to them, most of it their own fault. I’m still not certain if Faheem stumbled onto the truth…

I did a lot of reading about psychology and behavioral disorders while writing Night Shift; so, naturally, I was inspired to write about myself, not in an autobiographical style but more as a novel with a central character who could be me. Thus, A Change of Pace was created to write about myself anonymously. There’s a little biography in there but not much; nevertheless, Jim Walsh is as close to me as I can imagine a character. I also noted some eery similarities to my life that were not intentional. Perhaps writing a pseudo-autobiography was therapeutic after all.

The cover sets the stage for this light romantic comedy about a fish out of water. Besides jumping from action/adventure to romantic comedy, I also did the cover artwork myself. I had used the same studio for the previous four books but this one seemed too simple for their expertise (they specialized in hand-painted fantasy art). Thus, the cover features the motorhome I was living in at the time and my old Land Cruiser, but I never lived in an upscale apartment in my life. That part is fantasy.

I love writing novels because it’s like binge watching several seasons of a favorite show and getting to know the characters intimately. There is so much that can’t be squeezed into the final text. Still, it can be fun to explore a stranger’s life for a few days, a span of time too brief to really get to know them, yet long enough to reveal something significant about their lives.

I took a break from writing novels to write a series of short stories that shared a common theme, which developed while working on them. I collected them together into Class of 1974. Imagine the different lives of people who graduated high school the same year, but had nothing else in common; until they all won the lottery.

These stories share two common themes: the title implies that the stories are tied to a rather dismal year in recent American history; the second commonality is more dependent on luck. I created the cover from a stylized Escher staircase showing people going nowhere, which seems appropriate for my cohort.

I think every writer should write short stories between major works. It’s like writing practice. And short stories are a great break from the concentration necessary to complete a novel, not to mention the lengthy timeline. I think the idea for Mirror Images originated in a dream (I can’t remember for sure) with a lot of images flashing past, nothing recognizable; it may have been my waking memory of a series of static dreams. At any rate the eventual result was a collection of stories sharing as many mirror metaphors as I could think of.

I fell in love with this photo I found on Shutterstock because it conveys so much in a simple black and white format, and it was a large image so it could be used for the entire paperback cover. Mirror Images contains a couple of stories I don’t care for (unhappy endings) and several I loved writing and enjoy reading over and over. I’d love to hear what you think.

That’s enough for this reboot post. Next time we dive deep into science fiction.

Publications Reboot

INTRODUCTION TO PUBLICATIONS

I’ve made a slight adjustment to my web page. Publications will now be automatically updated like a blog post (aspirational at best). This change will allow me to add comments upon reflection of my writing, which is an evolving process; however, it also gives me an opportunity to standardize the web page–I hate inconsistencies of every kind.

This first post in the Publications category is a summary of what was on the old web page. I’ve added a little here and there. Let’s begin at the beginning…

THE UNVEILED SERIES

Awakening of the Gods is the first book I wrote. I was inspired by watching documentary shows about ancient aliens. It was supposed to be a short story, but then well… I felt like the story ended without full closure even though it was meant as a single novel.

I became interested in the history of the fictional Inauditis people while writing Awakening, so I explored their ancient background in Servants of the Gods. This was fun to write because of our poor knowledge of what society was like 47000 years ago. I also had the opportunity to work with a professional illustrator, who produced the great cover from my description.

I wrote a clever ending for this story, which required that I write a third book in the series. In truth, these books were very enjoyable to write. Exiles of the Gods picked up the story shortly after Awakening with the same characters, but the central character became Pedro who happened to be the Pope.

The most enjoyable aspect of writing Exiles was integrating time travel into the developing story. It was very complicated and may be difficult to follow during a casual read. Of course, having introduced or at least implied the existence of malevolent actors on the world stage, I put a hook in at the end that required writing a fourth book to close the story.

The story became even more complex with the introduction of more players in War with the Gods.

It was worth the effort because the entire story was wrapped up, and I even managed to introduce God, or the nearest thing to it. The fascinating aspect of writing these books was how it forced me to think seriously about my beliefs. It has been suggested by a friend that this series is the basis of a religion. I hope not.

Review of “Satantango” by László Krasznahorkai

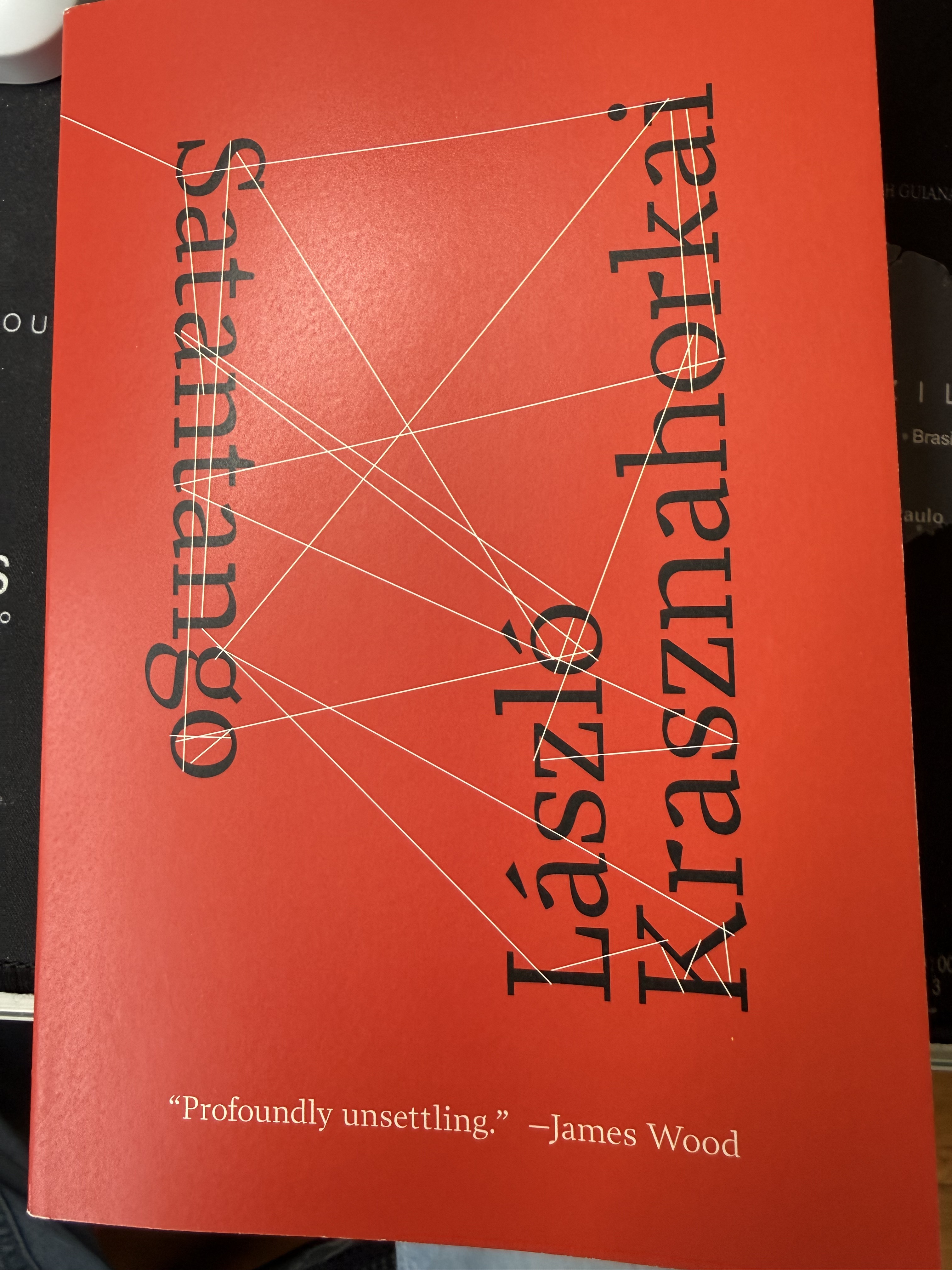

I don’t agree with James Wood, whose summary review is printed on the cover of this post-modern novel. This story is not profoundly unsettling; however, I think I know why they used that phrase.

This book was translated from Hungarian. I give two thumbs up to the translator, George Szirtes, because this was undoubtedly a monumental effort. There were very few grammatical errors and only a few missing words. The reason I am so impressed is that each twenty-plus page chapter comprised a single paragraph, which ranged across time and multiple characters, rather than focusing on a single character’s state of mind. Needless to say, this was a page turner; I couldn’t put it down until I finished each chapter/paragraph.

I couldn’t easily identify a plot, character arcs, or any other common literary themes in this work. The best way to describe it is as a literary journey into the lives of several individuals left behind in a changing society. No one is spared having their minuscule existence laid bare for the reader, even those who think they are in control. Everyone is portrayed as an unnecessary and redundant piece of machinery that is being tossed into the garbage after the social system on which they depended has broken and cannot be repaired. But none of them suspect the truth as they drag their tired minds and bodies through rain and mud towards a goal they know to be futile. If they are lucky, they can remain in stasis until they die, hopefully soon.

This bleak summary may sound “profoundly unsettling”, but only from an existential perspective. The reader shouldn’t be upset by their pathetic lives, however; there is no undue violence perpetrated on the characters, no shootings, not even self-recognition of their sorry state. They are oblivious. Perhaps that is why James Wood found it so disturbing; they didn’t even notice that the world had left them behind. I try not to read too much into novels, so maybe I don’t give as much weight to such literary analyses. I’ll leave that to scholars of literature.

You might be surprised to hear that I recommend this book, not for its literary value or deeply spiritual insight into post-modern civilization. It was simply fun to read a book where I didn’t have time to think about what came next. The author succeeded in bringing me, the reader, into a stream-of-consciousness experience in which I lost track of time.

I was just along for the ride…

Review of “The Folded Sky” by Elizabeth Bear

I’ll start with the easy part. The author has created an entire galaxy of worlds, which I assume define the “White Space Novel” series. There are even pirates, humans who want nothing to do with the modern world or aliens, which there are plenty of in this story. The action scenes aboard various spacecraft are well written and exciting.

The story is a mix of banal family drama and high-energy action scenes, all set to the backdrop of an imminent stellar explosion. The combination doesn’t work for me. I’ve been trying to figure out why, and I finally decided that there are too many antagonists. The story gets convoluted and it is hard to know who or what is an actual threat. The family scenes took up most of the first third of the book; I think the author realized they had lost track of the plot and jammed all the action they could into the last third.

At least twenty percent of the book is wisecracks by the first-person narrator. They used every simile and metaphor in the TWENTIETH CENTURY books. Maybe this is because the central character studies ancient civilizations, but her family had left earth only a few generations before the story takes place. It was very difficult to remember that they are a serious scientist with all the supercilious comments. Overall, this unnecessary self-reflection seriously detracts from the story, and adds a lot of pages.

There’s too much going on…but nothing. Once it became obvious that the pirates were just background noise, the book reduced to a whodunnit about a couple of attempted murders. Every seemingly hopeless situation is miraculously overcome with more fantastical alien powers. In other words, the story is contrived to fit the author’s predetermined ending. All authors do that to some degree, but it was a little too obvious in this book.

If you like space operas you’ll probably enjoy this book.

Review of “The Gulag Archipelago: Volume 2” by Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn

This three-volume book set won a Nobel Prize, so there isn’t much for me to add about its impact on the literary world. It describes the Soviet forced-labor, penal system in an entertaining style, blending personal experience with anecdotes and documented evidence from other camp survivors. It is nonfiction but neither is it autobiographical nor a documentary; it falls in a no-mans-land between personal opinion and an angry and disillusioned tirade. The first volume addressed the Soviet judicial system at a basic level, through the eyes of those ground up in its gears, which turned without purpose or guidance.

This volume explores life in the “Special Camps”, slave-labor facilities reserved for “58s”–political prisoners. The author describes what it’s like to become less than human through a relentless campaign of dehumanization and torture that lasts years, if not decades, for those consigned by the state to develop natural resources in regions where no one would voluntarily go. It is a brutal story of starvation, continuous mental and physical abuse, and death at the hands of the “natives'” own government. The vast majority of the “sons of the gulag” died in remote regions of Siberia, or at the gates of Moscow itself in camps, often comprising tents (in -30F weather!) over a period spanning decades. The inhumane conditions were often equally applied to women and children, as well as men.

The author convincingly portrays the Gulag as a microcosm of Soviet society, and, in my opinion, the human race as a whole. He exquisitely reveals the interaction of individuals as they form a new society, even in such harsh conditions. Cheks (Soviet masters) and Zeks (the 58s), joined by hardened criminals and exiled “free” people need each other to survive in the topsy-turvy world of Soviet Russia, but it is a marriage born in hell and consummated on the wind-ravaged, frozen steppe of Asia.

The English version was, of course, translated from Russian; the translator did an excellent job finding English and American phrases to match the original text–for example, the loyal Communists who found themselves labeled 58s and accepted their imminent demise in a death camp as due to something they did unawares, were, in the author’s opinion, pigheaded. So true.

This is another long volume in a saga that could go on for many more volumes, but there is only one more which I am currently reading. However, this is a review of this book; and my opinion is that it is too long, often awkwardly written, and doesn’t include enough autobiographical details. The author is trying to (I think) distance himself from what he refers to in Volume 3 as (paraphrasing) one of the most profound periods of his life.

Read it at your own risk.

Review of “Foundation and Earth” by Isaac Asimov

This is the final episode of the Foundation series, written by my favorite SF writer. I don’t know how one might properly finish such an epic series of novels (they cover more than 500 years), but I found the ending unsatisfying. Several questions raised in this book will remain unanswered…

Asimov writes in a very dated style, cumbersome and wordy, which dampens the reader’s anticipation. There is a lot of introspection by the characters, and the narrator is omniscient–knowing every character’s non-spoken emotional response in every scene. I don’t care for that style myself, but he uses multiple POVs most of the time.

The characters are on a galaxy-spanning search for Earth, the ancestral home of humanity, after 20,000 years of expansion into the Milky Way. They get into some tough scrapes and escape thanks to a character with uncanny powers of mental control that span galactic scales. Talk about non-local quantum entanglement! This story is as much about the potential pathways of civilization as their quest for Earth. How many cultures and phenotypes can evolve in twenty millennia? Very imaginative and creative.

In the preface, Asimov says he didn’t want to write any more Foundation novels, but the franchise’s resurgence among SF fans in the 80s put pressure on him (from his editor) to write this book. His reluctance to write it shows in the lackluster response to some questions and the silver bullet represented by one member of the group. However, as in his early days, he ups the ante in the ending, demonstrating one way all galactic roads might lead back to Earth, the cradle of humanity.

This book is fine as a standalone story and, to be honest, I didn’t remember much of the previous three novels. With SF there is always more backstory than the author can include. It’s is a fun book, especially the ongoing debate between the characters about individuality versus group consciousness. Despite the convincing arguments made for shared consciousness across the galaxy, I think something would be lost–maybe the unbridled creativity of “Isolates” like me experiencing reality alone.

Maybe I’m not ready for the future…

Review of “ALL THE DARK WE WILL NOT SEE” by Michael B. Neff

If only my sore eyes, bloodshot from pollen, stress, and lack of sleep, had noticed the first ill omen, waving like a red flag on Waimea beach when surf’s up, on the scintillating cover of this book. A list of names that reads like the playbill for Superman, after he had saved the world yet again, whose meaning I didn’t grasp until my mind had been dulled by drinking in this tale of star-crossed lovers swimming in a shark-infested bay connected to an ocean filled by prehistoric behemoths, a vast chasm only glimpsed by their perspicacious intellects, unobserved by unsuspecting mental midgets like myself. The forbidding cover, a vigilant guardian of truth and their giant eagle, reached into the depths of my soul, like a Stephen King novel on a stormy night, and warned me as clearly as a sunny day, to go no further. Yet I was driven by the will of Vishnu …

Enough of that. My point is that this book is written like poetry, filled with allegory and metaphors. At first I thought this was a great way to reveal Edison Eden’s tragicomic perspective, but the author used it for the narrator … pretty much everyone whose point of view is displayed in this tragic tale of deception, manipulation, betrayal and outright insanity. The feelings of the characters are amplified wildly by the writing style. It was a bit much for me.

This is a well-written book with some annoying grammatical errors, e.g., systematic missing possessive apostrophes in the same person’s name. Almost like a machine wrote it. Probably the publisher’s editing software.

This is a work of fiction, so the Office of Special Counsel and several other whistleblower protection agencies, were replaced by the fictitious Office of Whistleblower Counsel in the novel. The author weaves a believable imaginary world around this dim space in a concrete bastion erected on K Street, populate by gods, demons, acolytes, and other celestial beings.

It isn’t my cup of tea, but it’s a good read if you like metaphorical writing …

Review of “The Ministry for the Future” by Kim Stanley Robinson

I’m not certain where to start. This long book (563 pp) is actually two books, one fiction, the other nonfiction, interweaved so that the reader can’t follow either story. The central plot involves a lonely middle-aged woman who finds a friend in the most unlikely of places. It follows her career with the Ministry for the Future over about 25 years. The title comes from the second, nonfiction, story wedged into the real story. This is the author’s vision of the world over the next few decades; global warming is a central theme, but there are many other questions. In fact the backstory takes over the book. About half the chapters are explanations of various economic indices, technologies, and social theories that relate to the current plethora of problems confronting earth and humanity. However, this nonfiction narrative is presented as fiction, i.e., no footnotes, references, or bibliography. I’m sure they tried to get all these details correct but I don’t know. At any rate, I don’t care for “what if” nonfiction.

The choice of narration style is confusing. In fact, there may be three books contained in these pages: the main story is told in a normal manner by a third person narrator, with multiple points of view (actually I think only two), and literary attention paid to mundane details in Zurich, Switzerland. But this is from the perspective of the central character, who loves Zurich, even though she never bothered to learn Swiss German (what?). I felt like I was learning German from all the street names and other paraphernalia.

The nonfiction book is a series of essays of various aspects of society and technology, including excruciating details about glacial mechanics (boring!), finance, etc. This is also told by a third-person narrator, like reading a technical report.

The third book is a series of comments and reflections by people who live through the time period presented in the book, all in first-person, often with no identification. They often have no bearing on the plot. Redundant. These are interspersed with metaphysical comments from … the sun, other nonliving agents. Kind of like poetic interludes. And there are the Socratic interludes, in which unnamed persons debate various philosophical points.

I see what the author was trying to do, but it doesn’t work for me. It reads like they had three manuscripts (or piles of notes) on their desk, and jammed them together. Thus there is no flow and the reader is always having to shift reading mode while looking hopelessly for a plot.

And then there’s grammar and punctuation. I was looking for a pattern here: run-on sentences that lost their subject on their meandering path; sentence fragments; quotation marks for dialogue … or not. I thought perhaps the three threads used different writing styles to punctuate their mood, but I found nothing. The main story used quotation marks haphazardly. I had to reread at least one sentence on every page, often more. This is a clumsily written book.

The cover proclaims that this is one of Barrack Obama’s favorite books of the year. I doubt he finished it, just like the person who gave it to me, three-quarters completed – I finished it, not because it was entertaining or a pleasant diversion. I’m just a stubborn reader.

I could go on, but it isn’t worth the effort …

Review of “Dreams in the Eternal Machine” by Deni Ellis Béchard

There is no surprise ending to this speculative science-fiction novel. The secret is in the title and explicitly introduced in the first few pages. Everyone on earth, including the planet itself, has been assimilated by an artificial super intelligence whose rapid development far surpassed its creator’s imagination. So what is the plot?

Wrapped in a science fiction cover is a Shakespearean story of betrayal between young people who accidentally meet in an American divided by civil war. Their story is integrated with their separate experiences after assimilation into the machine, and it remains unresolved. The only other evidence of a plot is the general decline in cognitive and emotional wellbeing of the majority of people. This process is explored through several characters whose importance to the plot is never clear. In fact, no one really stood out as being the central character, other than the two young people mentioned above. Having a plot doesn’t require the central character to succeed; failure is the stuff of tragedy and perfectly okay, but no one really struggled against the antagonist (obviously the eternal machine). Their situation is hopeless and there is no chance of escape — not even the slightest. Hopeless.

Given the lack of a coherent plot or even a central character, this story is fundamentally about the response of people to a hopeless situation in which there are no threats of any kind. The machine not only feeds and cares for its dependents, it creates any world they want to see and experience. Spoiler alert: Heaven gets old after a few centuries.

The writing is very good, and the author doesn’t miss a trick to get an agent’s attention and produce a popular book. It seems to me that agents probably don’t think very hard about the books they represent. And, of course, the reader doesn’t find out until it’s too late, the money spent. That’s how I felt. As far as the reviews, I never cease to be amazed at the glowing reviews written about this novel; I guess critics don’t read books either.

Recent Comments