Trinity House

Trinity House was written during the Covid pandemic and thus expresses my frustration with the divisions I was watching grow within American society. I didn’t want to write a dramatic story but that’s probably what it is. As the author I accept full responsibility for this dark comedy that attempts to explore the relationship between superstition and innate human behavior.

The professionally done cover encapsulates what is wrong with extreme religious beliefs. One side of the church’s lawn is well kept while the other is overgrown with weeds, the tree dying, yet the gardener is waving as if there were nothing wrong, oblivious of the damage he has done by his own acts. But he isn’t happy, far from it; his demons are haunting him.

I tried to capture the complex social environment of deeply conservative Christians torn between their dogma and the reality of life, the neighbors they are equally capable of loving or hating. I personally love the ending, but then I’m an agnostic, maybe an atheist. At any rate, it felt good to get yet another burden off my chest.

Publications: Deep Dives into Science Fiction

I’m not reposting these book descriptions in chronological order. They were originally written as my interest changed through time and in response to the news. This post focuses on four science fiction novels inspired by the news, and my visceral reaction to the simplified reality portrayed in pop culture. Thus, my attention turned to early reports of Artificial Intelligence, as Large Language Models were presented to the public. All the hype about deep-learning algorithms becoming intelligent after being trained on vast amounts of publicly available books, movies, images, etc. bothered me because, if the objective (intentional or not) is Artificial General Intelligence, these programs all missed the boat. For example, a human brain isn’t fed a stream of data to become the cognitive wonder we claim to be; it spends years processing and assimilating sensory data–touch, hearing, smell, sight, taste. So I imagined what might be occurring in a private lab somewhere, an event so profound it would change the course of civilization. It remains entirely possible that a scenario like that portrayed in Aida is actually playing out below the radar of mainstream media attention.

AIDA is an acronym for Artificial Intelligence Daughter Algorithm. It is the story of a heartbroken computer scientist who decides to create a daughter to replace the one he lost, along with his wife, during childbirth. But his creation exceeds his wildest expectations. The simple cover encapsulates the central theme of the book. Look at the picture closely and you will find that the beautiful woman depicted in the left side of the face is matched by an evil countenance on the right. There is no purpose in issuing warnings about unintended consequences because humans never look beyond the immediate horizon.

Writing Aida got me to thinking about AI and robotics so, naturally, I wrote another book on the subject. I wondered what would happen if an AGI hooked up with an advanced humanoid robot. One possibility is encapsulated in the title of this novel: it would be a Black Dawn for humanity if the wrong people got their hands on it. I wanted to call this book, AMANDA, the name of the central character. As you might have guessed that is an acronym–AMANDA is an Autonomous Mobile Anthropomorphic Neural-synthetic Deep-learning Architecture that has spent 16 years being raised as the daughter of a couple of computer scientists.

The naive Amanda needs a guide for her intellectual and emotional journey when her family is murdered and her body stolen. To add an interesting twist to the tale, I reintroduced the elderly writer from A Change of Pace as the author of the novel that influenced her parents: Aida not only impacted AMANDA’s creators, it also leads to its author (Jim Walsh) being pursued by the bad guys. Naturally, Amanda and Jim become unlikely partners in a quest of personal importance to both of them.

This is an adventure that doesn’t slow down until the end.

Apparently, I needed more adventure after writing Black Dawn, so I wrote a what-if novel about what might happen if the basic laws of physics, or the constants we take for granted, were to change. The result is Broken Symmetry, a story about a graduate student who finds herself the locus of a bizarre chain of correlated events–personal, social, and even geological–with no obvious causation.

The action in this story is too cataclysmic to keep under wraps, not when the San Andreas fault ruptures and Yellowstone caldera explodes, but that’s only the geological story. People begin to change and someone wants to stop the contagion. (Don’t they always?)

The Edge of Space was my response to a news story about Voyager One having communications problems after exiting the solar system. The story is told through the eyes of several characters with different perspectives. Their interactions are rife with speculation about what is occurring, from a young woman from Thailand to the president of the United States. As the story unfolds, these characters move in and out of each other’s lives.

I have written an outline for a sequel to this story of First Contact…

Publications: A Change of Pace

As much as I enjoyed writing the Unveiled books, I was ready for a change and, besides, I had some more issues to work through. I’m not generally a conspiracy fan but 9/11 got everyone’s attention, especially with that whitewash report the federal government produced. However, in Night Shift, I got distracted from the conspiracy theory and really dug into a tragic relationship between two people who couldn’t have been more different.

This book was a lot of fun to write, even though part of the story was tragic. I felt as if I knew Faheem and Sofia personally by the end. What a crazy couple, but they stuck it out despite their differences and what was happening to them, most of it their own fault. I’m still not certain if Faheem stumbled onto the truth…

I did a lot of reading about psychology and behavioral disorders while writing Night Shift; so, naturally, I was inspired to write about myself, not in an autobiographical style but more as a novel with a central character who could be me. Thus, A Change of Pace was created to write about myself anonymously. There’s a little biography in there but not much; nevertheless, Jim Walsh is as close to me as I can imagine a character. I also noted some eery similarities to my life that were not intentional. Perhaps writing a pseudo-autobiography was therapeutic after all.

The cover sets the stage for this light romantic comedy about a fish out of water. Besides jumping from action/adventure to romantic comedy, I also did the cover artwork myself. I had used the same studio for the previous four books but this one seemed too simple for their expertise (they specialized in hand-painted fantasy art). Thus, the cover features the motorhome I was living in at the time and my old Land Cruiser, but I never lived in an upscale apartment in my life. That part is fantasy.

I love writing novels because it’s like binge watching several seasons of a favorite show and getting to know the characters intimately. There is so much that can’t be squeezed into the final text. Still, it can be fun to explore a stranger’s life for a few days, a span of time too brief to really get to know them, yet long enough to reveal something significant about their lives.

I took a break from writing novels to write a series of short stories that shared a common theme, which developed while working on them. I collected them together into Class of 1974. Imagine the different lives of people who graduated high school the same year, but had nothing else in common; until they all won the lottery.

These stories share two common themes: the title implies that the stories are tied to a rather dismal year in recent American history; the second commonality is more dependent on luck. I created the cover from a stylized Escher staircase showing people going nowhere, which seems appropriate for my cohort.

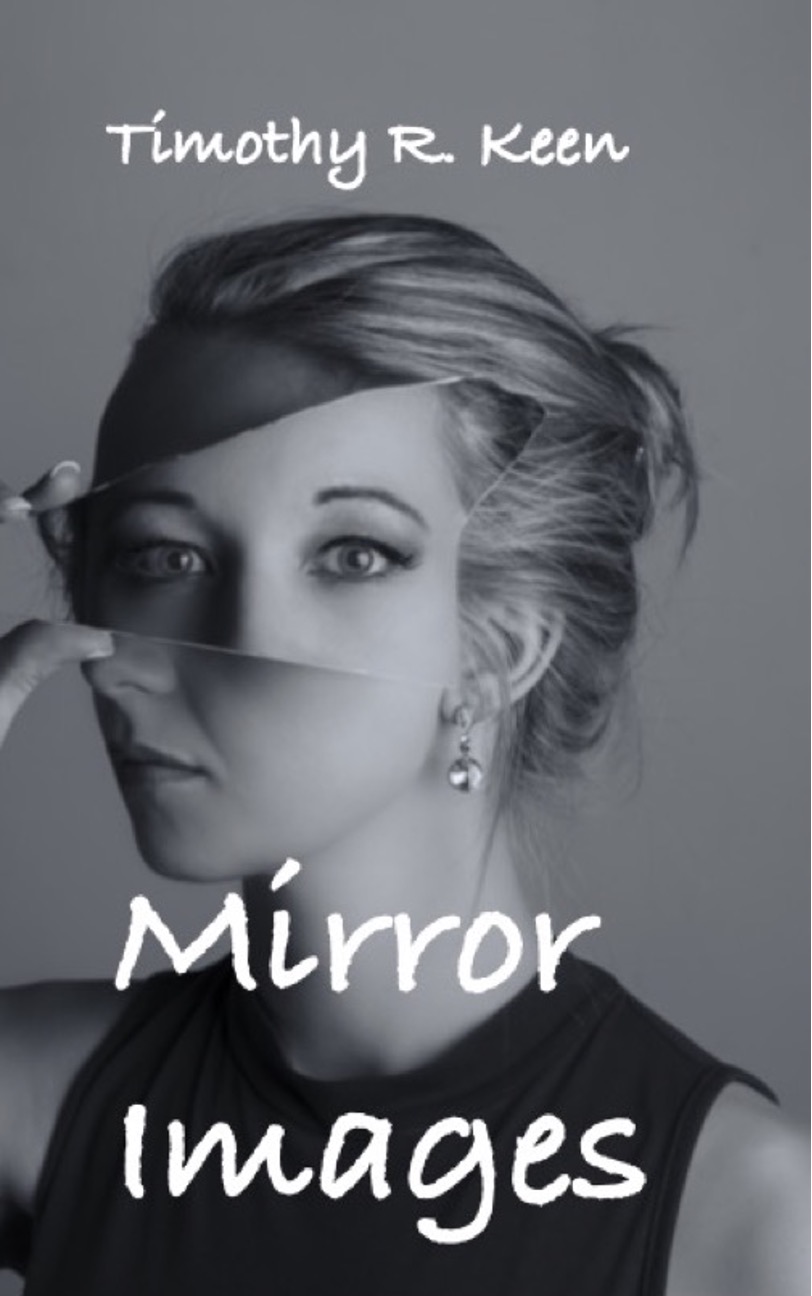

I think every writer should write short stories between major works. It’s like writing practice. And short stories are a great break from the concentration necessary to complete a novel, not to mention the lengthy timeline. I think the idea for Mirror Images originated in a dream (I can’t remember for sure) with a lot of images flashing past, nothing recognizable; it may have been my waking memory of a series of static dreams. At any rate the eventual result was a collection of stories sharing as many mirror metaphors as I could think of.

I fell in love with this photo I found on Shutterstock because it conveys so much in a simple black and white format, and it was a large image so it could be used for the entire paperback cover. Mirror Images contains a couple of stories I don’t care for (unhappy endings) and several I loved writing and enjoy reading over and over. I’d love to hear what you think.

That’s enough for this reboot post. Next time we dive deep into science fiction.

Publications Reboot

INTRODUCTION TO PUBLICATIONS

I’ve made a slight adjustment to my web page. Publications will now be automatically updated like a blog post (aspirational at best). This change will allow me to add comments upon reflection of my writing, which is an evolving process; however, it also gives me an opportunity to standardize the web page–I hate inconsistencies of every kind.

This first post in the Publications category is a summary of what was on the old web page. I’ve added a little here and there. Let’s begin at the beginning…

THE UNVEILED SERIES

Awakening of the Gods is the first book I wrote. I was inspired by watching documentary shows about ancient aliens. It was supposed to be a short story, but then well… I felt like the story ended without full closure even though it was meant as a single novel.

I became interested in the history of the fictional Inauditis people while writing Awakening, so I explored their ancient background in Servants of the Gods. This was fun to write because of our poor knowledge of what society was like 47000 years ago. I also had the opportunity to work with a professional illustrator, who produced the great cover from my description.

I wrote a clever ending for this story, which required that I write a third book in the series. In truth, these books were very enjoyable to write. Exiles of the Gods picked up the story shortly after Awakening with the same characters, but the central character became Pedro who happened to be the Pope.

The most enjoyable aspect of writing Exiles was integrating time travel into the developing story. It was very complicated and may be difficult to follow during a casual read. Of course, having introduced or at least implied the existence of malevolent actors on the world stage, I put a hook in at the end that required writing a fourth book to close the story.

The story became even more complex with the introduction of more players in War with the Gods.

It was worth the effort because the entire story was wrapped up, and I even managed to introduce God, or the nearest thing to it. The fascinating aspect of writing these books was how it forced me to think seriously about my beliefs. It has been suggested by a friend that this series is the basis of a religion. I hope not.

Review of “Satantango” by László Krasznahorkai

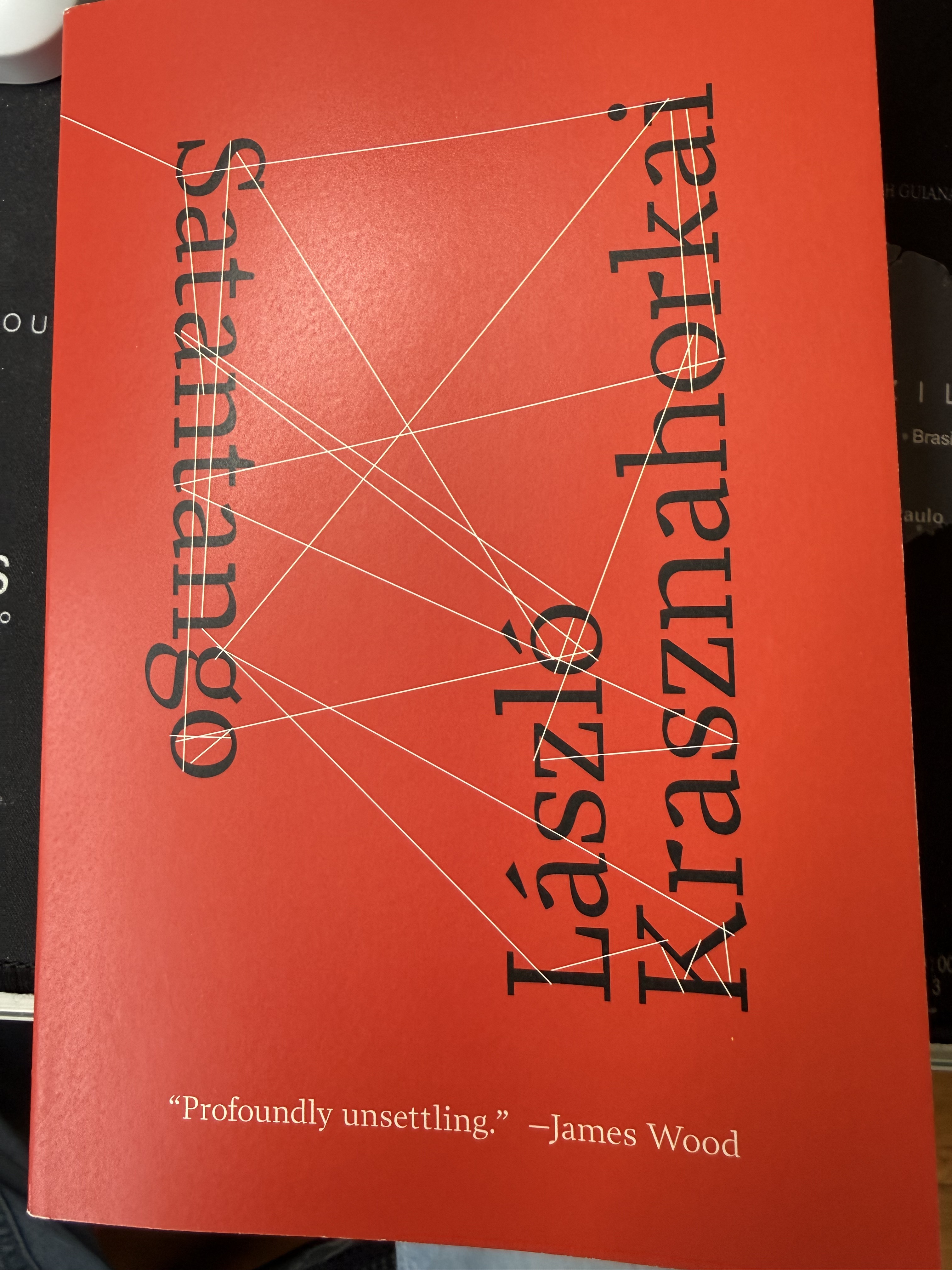

I don’t agree with James Wood, whose summary review is printed on the cover of this post-modern novel. This story is not profoundly unsettling; however, I think I know why they used that phrase.

This book was translated from Hungarian. I give two thumbs up to the translator, George Szirtes, because this was undoubtedly a monumental effort. There were very few grammatical errors and only a few missing words. The reason I am so impressed is that each twenty-plus page chapter comprised a single paragraph, which ranged across time and multiple characters, rather than focusing on a single character’s state of mind. Needless to say, this was a page turner; I couldn’t put it down until I finished each chapter/paragraph.

I couldn’t easily identify a plot, character arcs, or any other common literary themes in this work. The best way to describe it is as a literary journey into the lives of several individuals left behind in a changing society. No one is spared having their minuscule existence laid bare for the reader, even those who think they are in control. Everyone is portrayed as an unnecessary and redundant piece of machinery that is being tossed into the garbage after the social system on which they depended has broken and cannot be repaired. But none of them suspect the truth as they drag their tired minds and bodies through rain and mud towards a goal they know to be futile. If they are lucky, they can remain in stasis until they die, hopefully soon.

This bleak summary may sound “profoundly unsettling”, but only from an existential perspective. The reader shouldn’t be upset by their pathetic lives, however; there is no undue violence perpetrated on the characters, no shootings, not even self-recognition of their sorry state. They are oblivious. Perhaps that is why James Wood found it so disturbing; they didn’t even notice that the world had left them behind. I try not to read too much into novels, so maybe I don’t give as much weight to such literary analyses. I’ll leave that to scholars of literature.

You might be surprised to hear that I recommend this book, not for its literary value or deeply spiritual insight into post-modern civilization. It was simply fun to read a book where I didn’t have time to think about what came next. The author succeeded in bringing me, the reader, into a stream-of-consciousness experience in which I lost track of time.

I was just along for the ride…

Reseña de “El coronel no tiene quien le escriba” por Gabriel García Márquez

English

This is another short novel by Márquez, this time centered on an out-of-luck, retired military officer still waiting, after 15 years, for the retirement he was promised after the revolution. I can’t say anything about the grammar other than what I’ve said before: Spanish authors don’t like punctuation and, I think, they like to promote confusion. There is no plot, only a series of insignificant events that lead nowhere. The central character is probably the saddest inhabitant of his village, and the antagonist is a fighting cock he inherited from his deceased son. He feeds it rather than himself and his wife, hoping he can sell it after the next big fight–always the next fight. The story ends like it begins: waiting for the letter and for a better price to sell the champion chicken. What saves the story is the richness of the description of life in a poor Latin American village.

Español

Esto es otra novela menor por Márquez, esta vez centrada en un oficial militar jubilado y sin suerte que sigue esperando, después de 15 años, por la pensión de jubilación que se le prometió después de la revolución. No puedo añadir nada a la gramática más allá de lo que dije antes: no quieren los autores espańoles la puntuación y (yo pienso) ellos quieren promover la confusión. No hay trama sino solo una serie de eventos que no conducen a ninguna parte. El personaje central es probablemente el habitante más triste de su pueblo y su antagonista es un gallo de pelea que él heredó de su hijo muerto. El lo alimenta en vez de a él mismo y a su esposa, esperando que pueda venderlo después de la próximo gran pelea–siempre la próxima pelea. La historia termina como comienza: el coronel está esperando la carta y un mejor precio de modo que pueda vender el gallo campeón. Lo que salva la historia es la riqueza de la descripción de la vida en un pobre pueblo latinoamericano.

Review of “Astra” by Cedar Bowers

This novel relates an unpleasant story in a very interesting manner. The story unfolds through the eyes of ten people who encounter the central character during her life. By unpleasant, I don’t mean it is a tragedy; in fact, it is a relatively benign tale of the life of a person with a problematic childhood. What makes it so interesting is seeing Astra through multiple perspectives. However, she does appear in all of the chapters and participates in dialogue. The picture that emerges is complicated by the biases of the characters who interact with her, but it is not a happy image.

Despite the interesting story that unfolds through multiple points of view, sometimes it seems that the characters sound similar; the underlying theme appears to be self-absorption, which can seem cynical but is probably realistic. Astra doesn’t do what people want her to do. Different characters respond in unique ways as they contribute to the story.

I was somewhat disappointed by the ending because I expected this complex image to be shattered when Astra speaks for herself in the last chapter. Nevertheless, this story isn’t about plot or character development, but instead about how others see Astra. I didn’t like her, but the woman who appears from this kaleidoscope is realistic and probably representative of a large number of single mothers with disturbing histories.

I am glad to finally recommend a novel after so many disappointments.

Review of “Oaths (poems)” by F. S. Yousaf

I’m in over my head on this one. I can’t even format the title correctly. There is no punctuation in the title, but the subtitle is on the next line. Parentheses are the best I could do, which is what this review is.

I don’t read poetry, not because I thinks it’s useless–I just don’t read it. So I thought I should give it a try. I assumed that poets were masters of metaphor and all kinds of word relationships. Especially subtlety. There’s nothing subtle about the author’s pining for their youth, and to make things better for themselves. I don’t know if that’s actually how they felt when they wrote these sentimental poems, but that’s what this collection is about.

Not feeling abused emotionally or physically as a child or young adult, I had difficulty relating to the tenor of these short works. Nevertheless, there were some great metaphors and similes in here, along with some interesting presentation styles I appreciated (or tried to appreciate). I just couldn’t get into the often dark, frequently reminiscent, and always contemplative themes represented. I read a few pages now and then as a catharsis–for what I don’t know. Because the theme is so dark and deep most of the time, this isn’t exactly good meditation material.

I don’t feel qualified to express an opinion about this work, but the topic turned me off. But that’s just me, and I am a beginner at reading poetry. In fact, I had to Google how to read poetry. I even tried memorizing some of them to be sure I had read them correctly. I’m not giving up on poetry and, in fact, I’ll be starting another collection I purchased along with this one. I’ll let you know what I think.

If you enjoy deeply introspective poetry, you might already be familiar with the author’s work…

Review of “The Folded Sky” by Elizabeth Bear

I’ll start with the easy part. The author has created an entire galaxy of worlds, which I assume define the “White Space Novel” series. There are even pirates, humans who want nothing to do with the modern world or aliens, which there are plenty of in this story. The action scenes aboard various spacecraft are well written and exciting.

The story is a mix of banal family drama and high-energy action scenes, all set to the backdrop of an imminent stellar explosion. The combination doesn’t work for me. I’ve been trying to figure out why, and I finally decided that there are too many antagonists. The story gets convoluted and it is hard to know who or what is an actual threat. The family scenes took up most of the first third of the book; I think the author realized they had lost track of the plot and jammed all the action they could into the last third.

At least twenty percent of the book is wisecracks by the first-person narrator. They used every simile and metaphor in the TWENTIETH CENTURY books. Maybe this is because the central character studies ancient civilizations, but her family had left earth only a few generations before the story takes place. It was very difficult to remember that they are a serious scientist with all the supercilious comments. Overall, this unnecessary self-reflection seriously detracts from the story, and adds a lot of pages.

There’s too much going on…but nothing. Once it became obvious that the pirates were just background noise, the book reduced to a whodunnit about a couple of attempted murders. Every seemingly hopeless situation is miraculously overcome with more fantastical alien powers. In other words, the story is contrived to fit the author’s predetermined ending. All authors do that to some degree, but it was a little too obvious in this book.

If you like space operas you’ll probably enjoy this book.

Reseña de “Crónica de una muerte anunciada” por Gabriel García Márquez

Este libro fue muy difícil de leer. Un hombre inocente es asesinado por gemelos que creen que él arruinó la reputación de su hermana y destruyó la noche de bodas. La historia relata eventos previos a la muerte. Es un asesinato por venganza en un pueblecito pobre en el que una novia debe ser virgen. Toda la gente sabe sobre el plan de los gemelos pero espera en fascinación. Es una muerte brutal, acto cometido a plena vista. El narrador investiga el crimen y descubre la verdad después de muchas entrevistas con testigos años después.

La novela está escrita en español coloquial y es probablemente demasiado difícil para un estudiante como yo. Yo nunca sospeché que el español tuviera tanto sinónimos para palabras comunes. No pienso que aprendí ninguna palabra nueva. Sin embargo no me gusta narrador omnisciente, especialmente en español porque es imposible para mantener los caracteres cuando sus pensamientos y actos se confunden. La autora usó nombres completos pero esto solo aumenta la confusión. Para complicar las cosas el asesinato se describe varias veces por diferentes perspectivas. Oh, Dios!

Yo elegí este libro porque es corto pero ahora deseo que nunca hubiera leido! Brutal. Triste. Otro ejemplo de Garcías conocimiento sobre cultura latina.

Recent Comments