Galway … and Beyond

Figure 1. This photo shows the post-glacial, Pleistocene surface of the Carboniferous (320-300 Ma) limestone we’ve seen throughout Southern Ireland. The paucity of stone walls in the area suggests that boulders deposited by a glacier were less common here; the absence of drumlins or moraines further suggests that this area was scraped clean of loose material before the glacier retreated for the last time about 20 thousand years ago.

Figure 2. These layers of limestone are dipping at less than 20 degrees (field guesstimate), revealing different strata within the section. Low hills within the area indicated by a pin in the inset map of Fig. 1 were constructed of such tilted strata.

Figure 3. Geologic map of Ireland with the region discussed in this post highlighted by a black rectangle. The blue areas are the limestones we’ve seen before, indicated in the stratigraphic column (right of figure) with a matching arrow. These are the youngest rocks in this area. The pink area at the top of the study area is Ordovician (gray arrow in stratigraphic column), between 495 and 440 million-years old; these sedimentary and volcanic rocks are much older than the limestone. We’ll be focusing on Cambrian (545-495 Ma) sandstones that have been metamorphosed after burial and heating. This is the yellow-shaded area on the map and stratigraphic column. These are the oldest rocks we’ve seen in Ireland. Note the red area, and arrow in the lower map key (igneous rocks are shown separately in this map). These are Ordovician in age and thus much younger than the metasediments we’ll be looking at in this post.

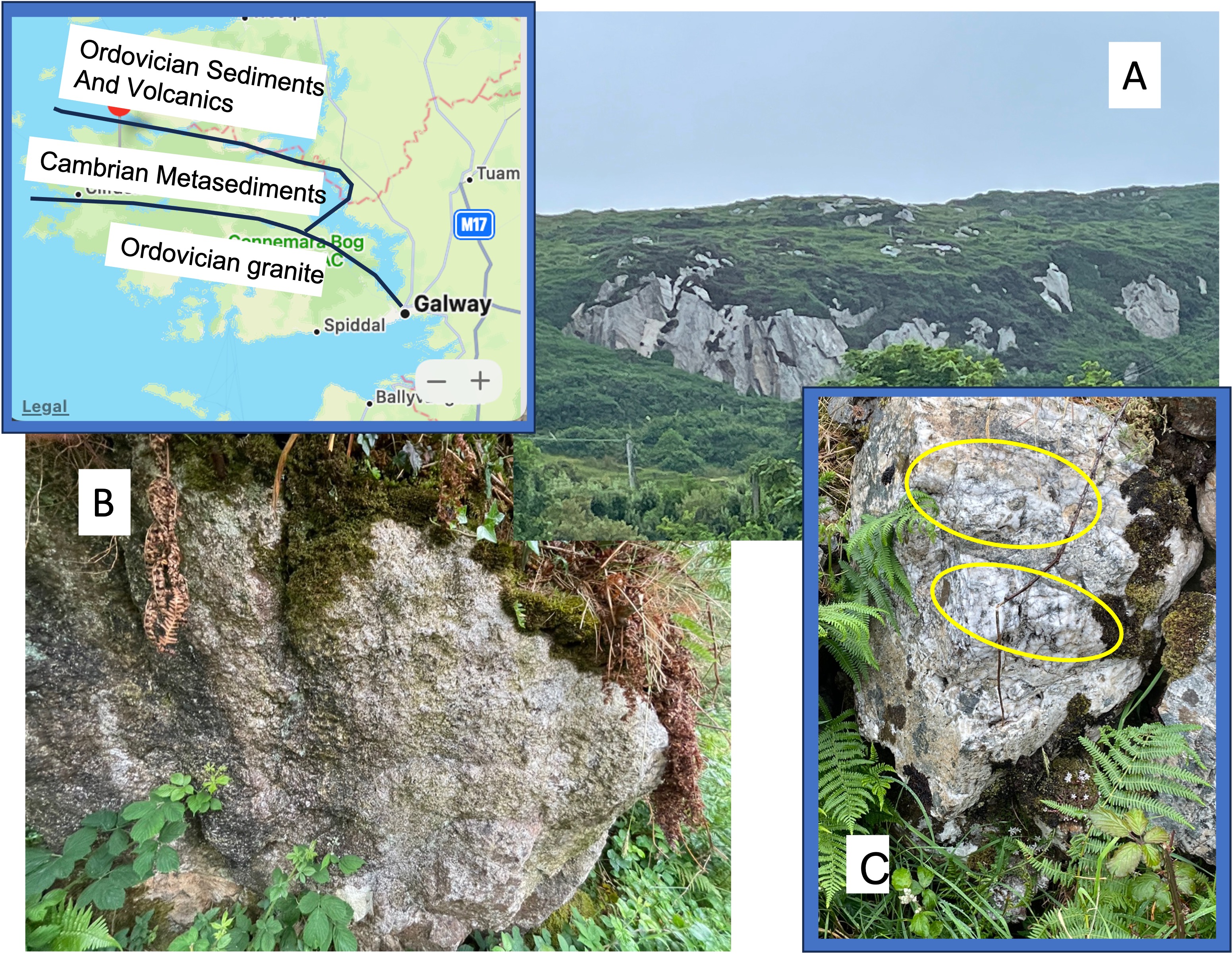

Figure 4. The inset map focuses on the upper-left portion of the inset map in Fig. 3. The three main rock types introduced above are labeled for clarity; note the presence of older (Cambrian) metasediments sandwiched between intrusive granite and sedimentary and volcanic rocks of Ordovician age. This curious stratigraphic relationship is due to an orogeny that occurred during the Ordovician geologic period. Cambrian sediments, mostly sand and shale, were buried several miles beneath the surface, when even deeper rocks melted to form magma, which rose as granite. The sediments were heated under moderate pressure, and then injected with fluids from the magma. The Ordovician sediments were deposited during this orogeny but were not buried as deeply as the subjacent Cambrian rocks.

Plate A shows a typical exposure of the Cambrian metasediments. Note the general appearance of a bedding plane, tilted steeply, facing towards the camera. Plate B is a boulder (possibly loose) of weathered meta-sandstone that reveals a dense area (lower right of outcrop) and indistinct bedding with resistant grains (probably quartz) set in a weathered matrix of darker material. Plate C, a photo taken less than a mile from Plate B, shows a small boulder comprising mixed grain sizes, with quartz inclusions (circled in yellow). The heterogeneity of this sample indicates that these sediments weren’t buried deeply enough for recrystallization to occur AND they were close enough to the magma to be injected with fluids .

These samples were observed near the boundary with the Ordovician granite (see inset map). These same sediments look very different further from the granitic intrusion.

Figure 5. Photo of the Cambrian metasediments further from the boundary with the Ordovician granite. The topography here (see inset map of Fig. 4) consists of a series of high, steep mountains comprising these resistant rocks.

Figure 6. Images of outcrops (in-place rock) away from the intrusive contact zone. (A) This photo (two-feet across) shows nearly vertical bedding planes, indicated by a yellow line. Note the uniform surface of this quartzite, which retains original bedding, as shown by dark laminae. (B) This photo shows a contact (yellow line) between the quartzite and a dark rock, which cuts across sediment layers (horizontal in the photo). This stratigraphic enigma may be caused by differential weathering along a fracture, long after deposition and subsequent deformation. (C) This close-up (photo is two-feet across) shows quartz veins dispersed within quartzite.

Let’s quickly return to the inset map of Fig. 4. Now that we know that the sedimentary layers were tilted almost 90 degrees during a mountain-building period, it makes sense that the Cambrian sediments are juxtaposed between younger rocks; they were intruded by granite, while younger sediments were deposited on top of them. These older rocks were heated to a higher temperature by contact metamorphism, and injected with magmatic fluids.

Figure 7. This figure shows a high-resolution image (inset) of the area we discussed in this post. The lower part of the map coincides with the Ordovician granite and the upper part reflects glacial carving of the Cambrian metasediments. Granite weathers much faster than quartzite and is less resistant to physical erosion; thus, the bogs we encountered on our drive are located to the south. This weathering occurred after all of these rocks were tilted during the Paleozoic, and uplifted during the Mesozoic; but before glaciers moved southward (black arrow), forming steep hillsides devoid of soil and trees, during the Pleistocene. That’s a time span of 200 million years.

Summary. Mountain building in Northern Virginia was active between 1000 and 500 Ma. Erosion has removed all geological evidence from the rocks I’ve seen in Virginia, until 200 Ma, when Pangea was torn apart; and North America and Europe were created.

About 550 Ma, sandy sediment was being deposited in shallow seas of Southern Ireland, continuing for at least 100 million years while magma collected in the shallow crust, producing granite intrusions for another hundred-million years. During this dark age in Virginia, the mountains grew then eroded in Ireland and a shallow sea formed, filling with sand, silt, and mud; the shells of marine invertebrates collected in this now-quiet marine environment.

Glaciers never reached Virginia but they covered Ireland throughout the Pleistocene, transforming its landscape.

That’s it in a nutshell …

So far.

Trackbacks / Pingbacks