Kilkee Cliffs: A Closer Look at Late Carboniferous Delta Sediments

Figure 1. Wide view of the area called Kilkee Cliffs, showing the nearly horizontal bedding plane of these Late Carboniferous (about 310 Ma) rocks. Note the slight dip towards the right (northeast) of the cliff in the distance. These are the same rocks I saw at Foynes.

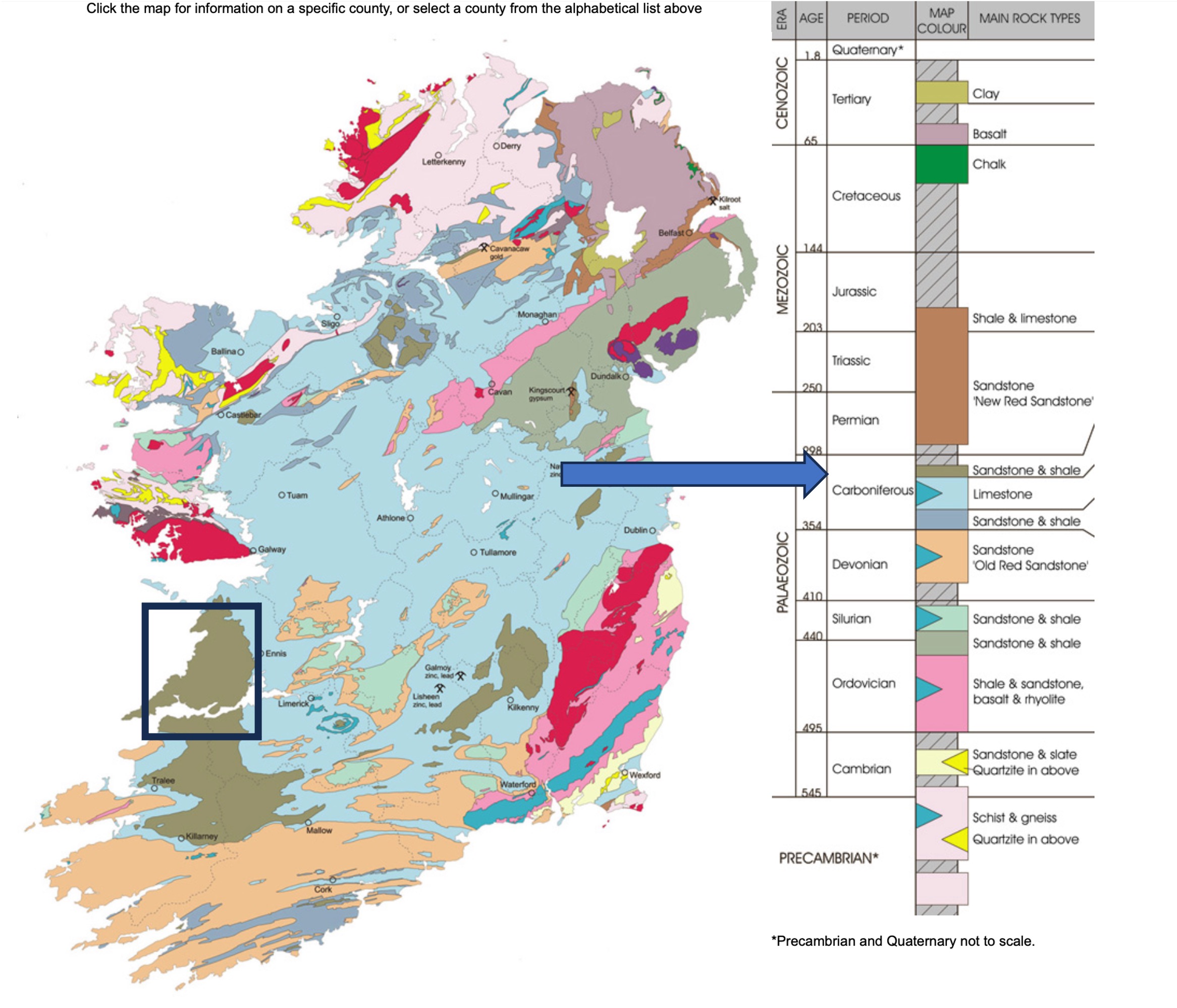

Figure 2. Geologic map of Ireland, showing the area reported on today and in the next post, colored brown and offset with a black rectangle. The view in Fig. 1 is looking to the northwest near the center of the rectangle. The stratigraphy of Ireland is shown on the right, with the arrow indicating where these rocks fall within the sequence that has been identified in Ireland. The limestones I reported on earlier are just below these rocks in the stratigraphic column.

Figure 3. These rocks comprise thin beds of sandstone and shale towards the top of this image, and thicker beds of sandstone and siltstone lower in the section. These rocks have been identified as turbidites and delta sediments. I discussed this in the previous post.

Figure 4. Close-up of a bedding plane within the thin beds shown in Fig. 3. The surface is covered with elongate ripples in the background, and more lunate ripples towards the lower-right. These ripple marks are more common in a nearshore environment (e.g. water shallower than 100 feet) than in turbidity flows, which are not as spatially uniform.

Figure 5. Detail of wave ripple marks. The water depth of the silty sediment in which they formed depends on several factors: grain size, surface wave properties (e.g. wave height and period), water depth; thus, the exact water depth cannot be determined. However, if these ripples were buried by a sudden influx of sand/silt during a storm, the water would have been deeper than if the waves were fair-weather and the silt/sand was introduced by a river flood.

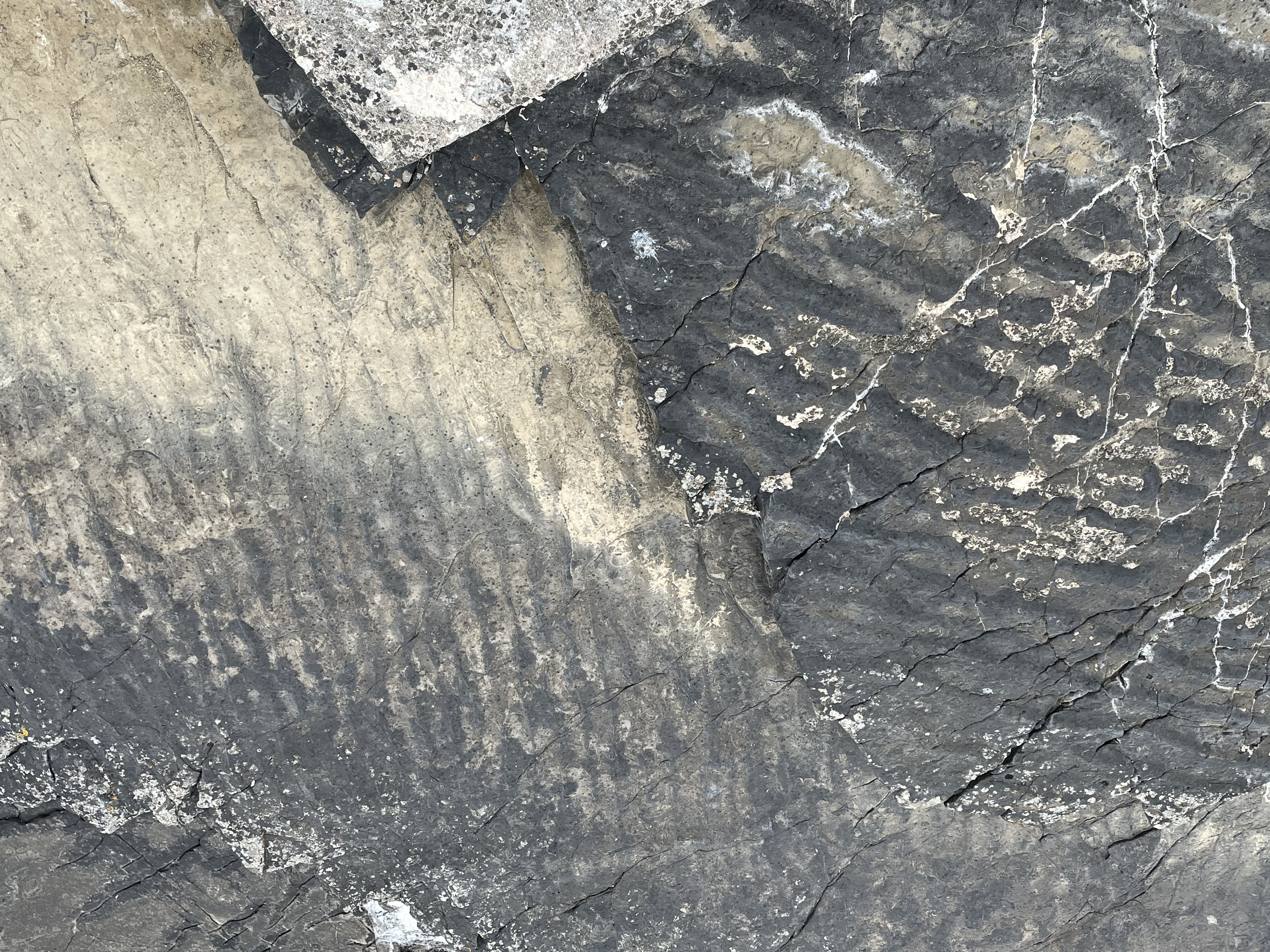

Figure 6. This image (looking down) shows ripple marks on bedding planes less than six inches apart vertically, in sediment deposited within months. The upper ripple marks (finer and more continuous) indicate waves arriving from the left of the photo; the lower (darker and larger) ripple marks suggest waves coming from the top of the photo. If I had to guess, I’d say that the older ripples were formed during a storm (i.e. larger waves produce larger and more irregular sand ripples); the younger set (buried within a few months) suggest quieter conditions. We don’t see details of past environments preserved much better than this.

Figure 7. This photo shows a set of uniform joints as X’s in the center of the image. They are very dense and form right angles. Sets of these joints occurred about 20 feet apart. These sets of joints were aligned with fracturing and preferential erosion along lines oriented from the top to bottom of this photo; the ‘V’ at the top of the image is the seaward extension of one such set of joints; the white patch in the upper-center shows where a layer has spalled off. The same delamination can be seen in the foreground. Imagine layers of paper being folded slightly; they slip against each other. The rock seen in this photo did that and, because it was no longer soft from burial and geothermal heating, it fractured on the outside of bends as the layers slipped.

Figure 8. This photo (image width is about two inches) shows crystals filling some of the joints as seen in Fig. 7; this could be quartz or calcite, but the orientation of the crystals’ long axes at an angle to the joint margins suggests that they formed during slippage, i.e. as the layers were sliding past each other. This is probably calcite, which precipitates readily from ground water (e.g. stalactites in caves) whereas hydrothermal fluids rich in quartz are rare without a nearby source of magma. There is no evidence of that in this region at this time.

These rocks weren’t folded or faulted as we would expect if this area was compressed during collision of the porto-North American and porto-European tectonic plates during the Paleozoic era. Maybe these sediments were deposited when mountains were uplifted during that ancient orogeny.

As I said before, mountains are as often as not identified by their erosional remains rather than their cores …

Trackbacks / Pingbacks